Chapter 8

Strategizing and Going Public

By Blanche Hyodo

During the mid 1980s, concern in Toronto’s Japanese community escalated between the JCCA and others in the community. At the last public meeting of the Sodan Kai held at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, the Toronto JCCA was given the mandate to form a Toronto Redress Committee comprised of all the Japanese Canadian organizations in the Greater Toronto area. However, instead of forming an independent, democratically elected body, the JCCA set up this new committee as a subcommittee of the Toronto JCCA.

The problem arose when the JCCA executive voted in a slate of 18 committee members, most of whom were JCCA supporters. They further voted in the entire Toronto JCCA executive to the new Toronto JCCA Redress Committee. Since each member had a vote, they could easily out-vote all the other community groups on the committee, as each group had but one vote.

Underlying this concern were the meetings that were fraught with disregard for parliamentary procedure and rules of fair play. Those who did not support the Toronto JCCA were clearly singled out. They could barely get a motion on the floor, and when they did it was either tabled or out-voted. Any items added to the agenda by the dissenters were invariably placed at the end of the agenda. Thus, time often ran out before these items could be addressed.

By this time, some of the nisei were very upset with the way the Redress campaign was progressing. The challenge was to find a way that would enable them to work together more amicably and cooperatively with the JCCA on the common goal of Redress. However, their efforts were constantly being thwarted, and so they ended up holding meetings at one another’s homes to plan new strategies that might lead to some success in democratizing procedures to give everyone an equal voice.

Initial meetings took place at the home of Matt and Nobuko Matsui, but by 1984, our little group of “interested individuals” had expanded, and more space was urgently needed. In order to provide “The Concerned Nisei and Sansei” (as the “interested individuals” were loosely referred to then) an opportunity to meet and work together on the Redress issue, Marjorie and Stan Hiraki came forward to offer the use of the new two-story addition to their home. There they hosted a party for the Sodan Kai on March 11, 1984. Twenty-two people attended that evening, forming the nucleus of what would eventually become the Toronto Chapter of the NAJC.

Unflagging Support

Our first semi-official meeting at the Hiraki residence was held on March 22, 1984, after which we met approximately twice a month until late fall, 1984. Then Misao and Wesley Fujiwara offered us the use of their home for our meetings so that Marjorie and Stan could get a long overdue break.

While we were still meeting at the Hiraki home, we were a very informal group with no name, no secretary, no treasurer—and no money. The Hirakis’ contribution to our common cause went beyond the mere use of their home for our meetings. They opened their hearts in countless other ways as well. Supplies of paper cups, plates and napkins, snacks, tea and coffee were on hand at every meeting. This translated into a lot of extra shopping for Marjorie. She also went to a good deal of trouble to ensure that everyone had a place to sit. It became a regular routine for her to borrow chairs from the waiting room of her dental practice on meeting nights, and she was often obliged to go knocking on her neighbours’ doors to scrounge up even more chairs for these mostly well-attended gatherings. At the May 3, 1984 meeting, 25 people attended, among whom were Hide Shimizu, David Suzuki, Roy Miki and Art Shimizu.

Stan made up agendas for all the meetings, running off copies for every member of the group. At one time, there were two separate meetings going on in their home simultaneously. Joy Kogawa and her group met downstairs, while the regular group met on the main floor! At times, the Hirakis must have felt that their home had been turned into a train station!

When the meetings ended, the Hirakis faced the further chore of tidying up. Chairs were returned to their neighbours and to the waiting room of Marjorie’s dental office. Putting their normally neat home back in order meant many a long night for these two professional people who had already put in a full day’s work.

Aside from hosting the strategy meetings, Marjorie and Stan bore various other miscellaneous Redress expenses such as: stationery, postage and long distance calls to NAJC centres in Vancouver, Ottawa and Winnipeg. The cost of that crucial telegram to David Collenette to halt parliamentary proceedings on the flimsy settlement package initiated by the JCCA was another expense they undertook in the cause of Redress. It was from the Hirakis home that we made phone calls back and forth to Art Miki who had had no previous knowledge of the impending settlement announcement in the House of Commons. The timely intervention of the telegram to Collenette saved the Japanese Canadian community from the humiliation of a meaningless settlement without individual compensation. To this day we remain indebted to Marjorie and Stan.

The Fujiwaras Open Their Doors

Wes and Misao Fujiwara lived in a large three-storey house near Yonge Street close to public transportation. They offered to take the load off the Hirakis by hosting the executive meetings on the third floor of their home. From the fall of 1984 to the spring of 1985, we met regularly at the Fuijwara residence where Misao graciously served coffee and refreshments while we planned strategies against the opposition who constantly schemed to discredit us.

By this time the battle lines had been drawn between the NAJC supporters and the Survivors’ group. Those representing the Japanese Canadian National Redress Association of Survivors (or The National Redress Committee of Survivors) were determined to obstruct us in every way possible and we had to be prepared to counter their attacks. Most of the meetings held at Wes and Misao’s house were to plan defensive strategies and to respond in the The New Canadian by presenting our side of the story. West took on much of this journalistic fencing with people like Vic Ogura of Montreal as well as the opposition in Toronto.

Both Wes and Misao had extremely busy medical practices and yet they made time to actively participate in the struggle for Redress. In view of their considerable professional commitments, the degree of their Redress involvement was amazing to most of us NAJC supporters.

It is a well-known fact that on more than one occasion when called at his office to attend a crucial, emergency meeting, although his waiting room was full of patients, Wes would have his nurse cancel the appointments while he immediately dashed downtown to the meeting.

Bill Kobayashi remembers receiving a phone call at his office from Elizabeth Wilcox, assistant to Jack Murta, the newly appointed minister of multiculturalism. She was calling from Vancouver to advise Bill that Mr. Murta was leaving for Toronto to meet Japanese Canadian community representatives at the Sheraton Hotel that afternoon! Bill immediately called Wes who once again cancelled all his appointments and hurried to the Sheraton.

This was Jack Murta’s initial exposure to the Japanese Canadian community and his first words were, “If I’m going to err in my decisions, I would err in favour of the issei over the nisei.” The new minister seemed to have been well coached in the policy of the Survivors group, but not well enough in the pronunciation of issei and nisei, which he pronounced “eesai” and “neesai”.

Bill and Wes noted that all the other Japanese Canadians present were supporters of the Survivors’ group. Mr. Murta asked each individual for his/her views on Redress. All indicated their support for group compensation. One participant at the meeting expressed fear of a backlash from the non-Japanese community if individual Redress was pursued. Bill and Wes stated their support for the NAJC position as the legitimate voice of the JC community.

After the meeting, Bill and Wes were approached by Doug Bowie, an official of the Ministry of Multiculturalism who had also attended the meeting. His words were, “I suspected there were opinions other than those expressed by this Survivors’ Group.” He then invited us to Ottawa. Subsequently, Kunio Hidaka, Bill Kobayashi, Matt Matsui, Roger Obata and Harry Yonekura flew to Ottawa and were escorted by Ottawa resident Fred Kamibayashi to a meeting with Doug Bowie and Orest Krulak. The two government representatives listened attentively to the NAJC viewpoint. As a result of this meeting, Doug Bowie was noticeably supportive of the NAJC position during the Redress negotiations that were to follow.

So not only did the Fujiwaras offer their home for strategy meetings, but Wes made it his personal business to publicly refute the opposition’s distorted, misleading comments in the community newspapers, and to maintain an NAJC profile with government officials by promoting the NAJC Redress position at every opportunity. He did all this while carrying on his professional career as a medical doctor.

Misao also had an extremely busy practice at Women’s College Hospital in downtown Toronto. But it didn’t deter her from hosting our weekly meetings at her home. The small core of dedicated NAJC supporters who spearheaded the intense struggle for justice in Toronto will always remember the outstanding contributions of Wes and Misao during those crucial days of the Redress campaign.

Going Public at Harbord Collegiate

After months of networking and strategizing, it was time to get our message across in a wider public forum. Our group, still informally labelled “The Concerned Nisei and Sansei”, held a public meeting on July 19, 1984 at Toronto’s Harbord Collegiate, 286 Harbord Street near Bathurst. Again, the Hirakis were instrumental in getting this event going. Stan gave up his summer vacation from Seneca College and poured all his energy into organizing this public meeting.

Finding an appropriate location was the first challenge because we had been hoping to rent the auditorium of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC). Unfortunately, this venue was not available since our organization was viewed as too “political” and the JCCC could not afford any misinterpretations regarding an affiliation with us. Church basements were regarded as too small for the number of people we were anticipating. Once again Marjorie Hiraki came to the rescue. One of her patients was a Toronto Board of Education trustee. Through this connection, Marjorie was able to get the Harbord Collegiate auditorium free of charge. This was a real godsend since we had no budget to speak of. It was also ideally located, was air conditioned and had a capacity of 750 people.

The next hurdle was trying to find a public address system. Seven microphones were required in that huge auditorium, three in the audience and four on the stage for the panelists. Harbord Collegiate had its own PA system, of course, but only school personnel and one experienced Harbord student were permitted to handle it. Resourceful Stan managed to locate this particular student to operate the PA system onthe night of the meeting. However, the student cancelled one week before the event, leaving Stan scrambling to make other arrangements at the last minute.

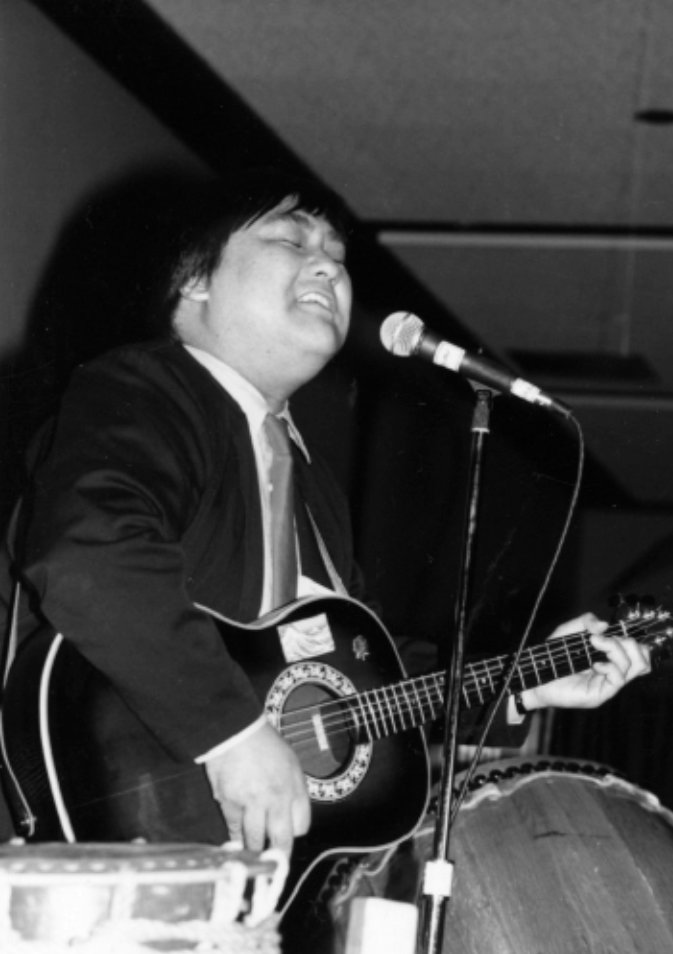

Around the time of our Harbord Collegiate meeting, Lech Welesa, the Polish union leader, was a common face on our television screens. He became synonymous with the word “solidarity” as this was the name and slogan of the party that he founded. It was a powerful word and Stan chose it to symbolize our event. He asked Matt Matsui to have a banner made to hang across the back of the stage. The banner read “Solidarity With the NAJC”. Terry Watada, also a member of the Seneca College faculty, agreed to bring his guitar and provide some appropriate entertainment for the evening.

The next task was publicity. Stan made a flyer, which was headlined, “REDRESS, WHAT’S GOING ON?” and had 1,500 copies made. He then scooted all over town distributing these copies to Japanese grocery stores, churches and other places frequented by members of the community. We also publicized our event in the community press. And just in case anyone missed seeing the widely distributed flyer, Marjorie organized a telephone blitz. All the Hirakis’ efforts proved worthwhile as we ended up with a turnout of over 500!

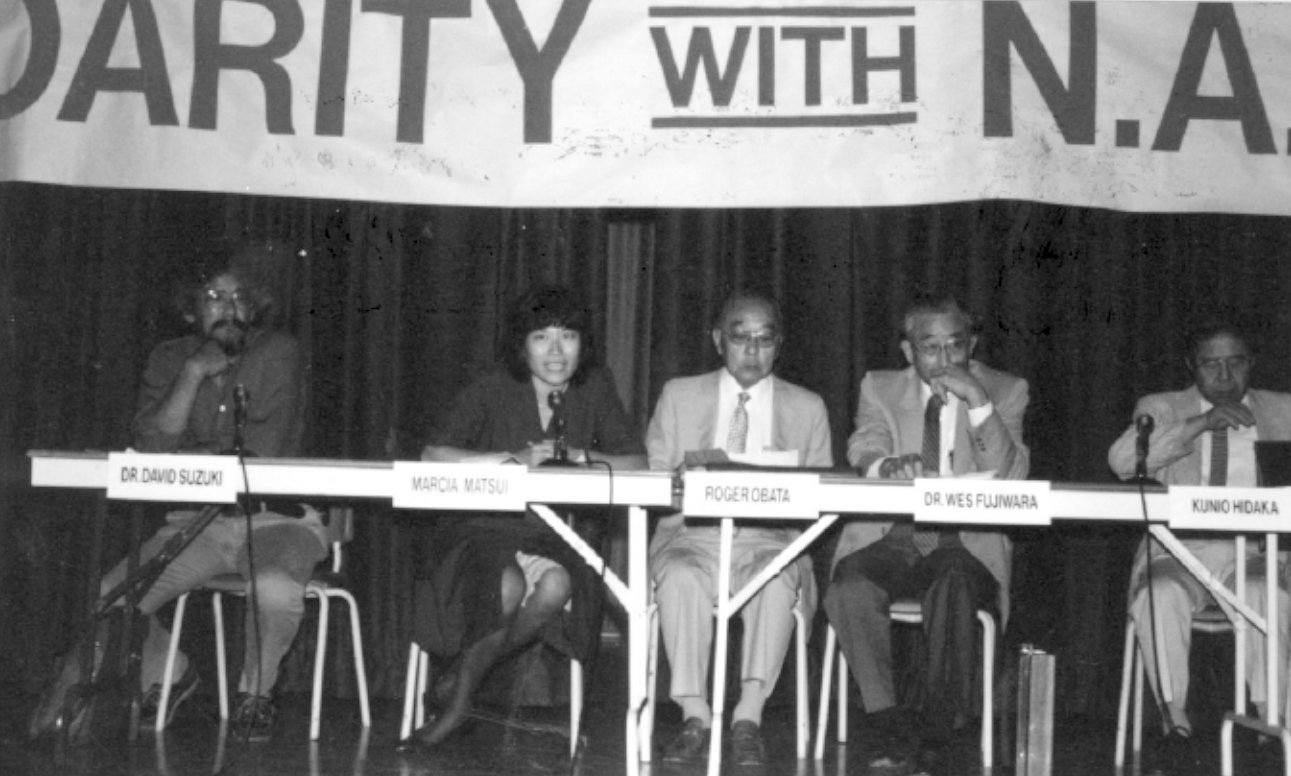

Chaired by sansei lawyer, Marcia Matsui, the panelists included Wesley Fujiwara, Kunio Hidaka, Roger Obata and our special keynote speaker, David Suzuki, who waived his usual fee for speaking engagements. Having Suzuki as our keynote speaker was an honour. He delivered an eloquent, inspiring speech in which he stressed the need to become unified and to see the Redress issue as a national justice issue for all Canadians. Entitled “Japanese Canadian Redress, An Issue for All Canadians”, Suzuki’s speech was later published in The New Canadian and was very successful in raising public awareness within the Japanese Canadian community, as well as bringing the whole Redress issue into proper perspective. Before his speech, many had perceived the Redress issue as merely a bitter internal dispute between two warring factions vying for political power within the community.

Suzuki’s speech was followed by Stan’s reading of a personal message from Art Miki who was on a teaching assignment in the Bahamas. Yuki Mizuyabu provided the Japanese translation for the issei in the audience. Everything seemed to be proceeding smoothly. We were relatively on schedule. The air conditioning was working. The audience was listening attentively. Then just after 9:30 p.m., during the question and answer period, something quite unexpected happened. The power went out! The power failure affected the main auditorium lights, the PA system and the air conditioning. Committee members checked the circuit breakers, but could not restore the electricity. Matt Matsui and Stan Hiraki searched the premises for the school caretaker, but he was also unable to restore the power. Then half an hour later the emergency exit lights ran out as well, leaving the auditorium in total darkness. The most bizarre aspect of the “lights out” episode was that the audience did not panic. Most of the people in the auditorium remained in their seats, patiently waiting for the power to be restored. In the meantime, we managed to continue the meeting with the aid of flashlights from our cars. In this way, we were able to record the names, addresses and phone numbers of about 100 people in the auditorium that night.

It is interesting to note that all the other buildings on Harbord Street that night had light. Harbord Collegiate was the only building experiencing a blackout. Many of us found this coincidence, if indeed it was a coincidence, very odd and at one point during the blackout a bold voice rang out of the darkness, “Jeez, somebody must have paid the caretaker off to have this!” It was a dramatic moment and illustrated to everyone the depth of the conflict in our community.

We will never know for sure what caused the famous blackout, but the suspicion of deliberate sabotage lingered for a long time. The most frustrating part of it all was not being able to record all the names, addresses and phone numbers of over 500 individuals who showed up at Harbord Collegiate that night. A complete list would have made our networking efforts infinitely easier over the months and years to follow.

Forging Ahead

Despite the unfortunate ending, the Harbord Collegiate evening marked a valuable turning point in the Redress movement simply because it helped raise the consciousness level of people who had previously given very little thought to the possibility of Redress. It also helped to strengthen our determination. At a meeting of the Concerned Nisei and Sansei on August 15, 1984, we made the decision to form an official separate group that would be set apart from any association with the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee. We wanted to create a democratic organization that would be recognized as a chapter of the National Association of Japanese Canadians with representation on the NAJC Council. Still known as the “Concerned Nisei and Sansei”, we eventually became the North York Chapter of the NAJC.

One of our immediate goals was to democratize the Japanese Canadian community in Toronto by pressing the Toronto JCCA to hold an annual general meeting. The organization had not had a general election in years. It was imperative that we get matters clarified for the federal government and for our own community. It was extremely confusing and misleading to have two official organizations representing the Japanese Canadians of Toronto.

We had a lot of work ahead of us and Stan and Marjorie continued to host our meetings. The sessions that went on during this period included the meeting of November 10, 1984 when Harold Hirose and Art Miki came to discuss the presentation of a Redress Brief to the federal government and the future NAJC budget. Then on March 28, 1985 we held an emergency meeting to discuss a petition from the National Redress Survivors’ Group (the new name for the group against individual compensation)—and the arbitrary expulsion of certain NAJC members from the TJCCA Redress Committee. Even lifetime members of the Toronto JCCA received official letters signed by Jack Oki and Ritsuko Inouye informing them that their membership in the North York Chapter automatically terminated their membership in the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee. We met at the Hirakis’ again on April 11, 1985, with Charles Kadota as our special guest, to draft a resolution to the NAJC Council regarding the actions of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee.

Looking back at that hectic period, I marvel at how the Hirakis and the Fujiwaras managed to tolerate so much disruption to their lives, meeting after meeting. It was understandable that both couples would one day become burnt out and admit that they needed a rest period. But we were not left scrambling for a new meeting place. Marjorie rescued us once again by contacting her school trustee friend. Through this connection, she was able to wangle a rent-free room for our meetings at Bedford Park School. The first meeting there was held on May 9, 1985.

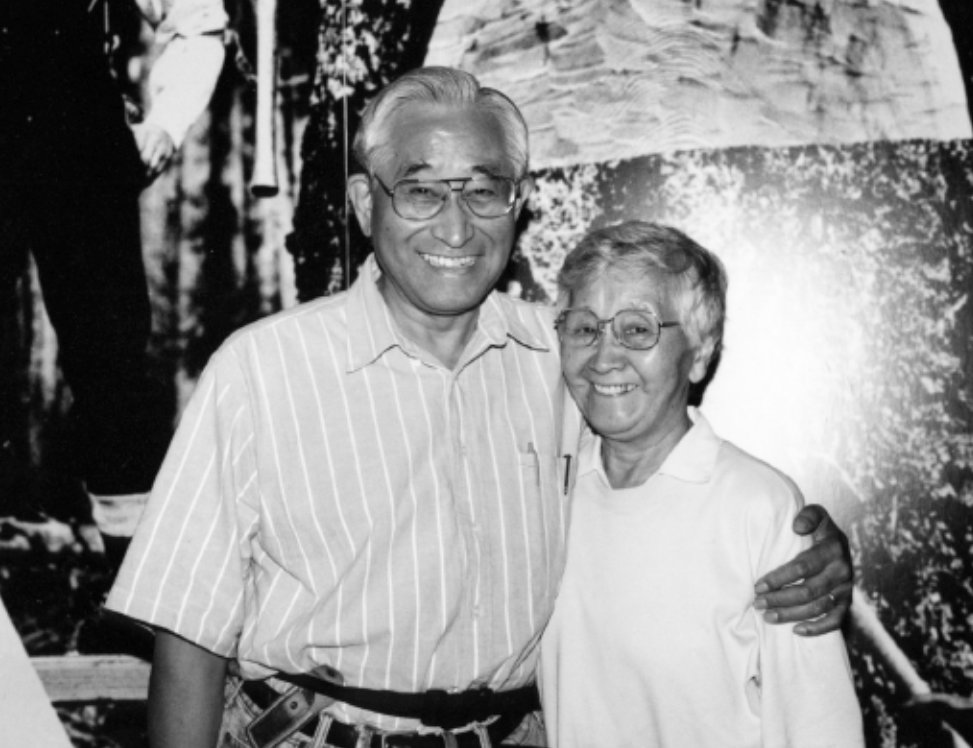

STAN HIDEO HIRAKI (above left) was born in Vancouver. As noted in Chapter 2, Stan left East Lillooet in December 1944 and headed for London, Ontario. In the spring of 1947 he moved to Toronto and later arranged for his family to join him. He received a B.A.Sc. in electrical engineering from the University of Toronto. After working in the electronics industry for many years, he joined the faculty of Seneca College. He retired in 1987. Stan has been president, vice-president and treasurer of the Toronto Chapter JCCA and board member of Nipponia Home and the Momiji Health Care Society. He was also a founding member of both the JCCC and the NAJC Greater Toronto Chapter, becoming the latter’s first vice-president.

MARJORIE WANI HIRAKI (above right) is married to Stan. They have one son named Lester. Marjorie has distinguished herself as one of the first nisei woman dentists in Canada. During the mid-1980s, Marjorie and Stan opened up their home for lengthy strategy meetings. The above photos show the Hirakis leaving their home for the famous public meeting at Harbord Collegiate on July 19, 1984. (Photos courtesy Stan and Marjorie Hiraki.)

A meeting held at 234 Ranleigh Ave., May 30, 1984. Left to right: Stan Hiraki (chairman), Wes Fujiwara, Harry Yonekura, Yuki Mizuyabu and David Suzuki. Others in attendance included Roy Miki and Art Shimizu. (Photo courtesy Stan Hiraki.)

Panel members at Harbord Collegiate meeting on July 19, 1984. Left to right: David Suzuki (keynote speaker), Marcia Matsui (chairperson), Roger Obata, Wes Fujiwara, Kunio Hidaka. (Photo: Stan Hiraki)

TERRY WATADA, long-time columnist for Nikkei Voice, became an activist after attending the meetings at the Hirakis. He was a stainch supporter of the Redress campaign and contributed to many events with his music. A man of many talents, Watada is a teacher, playwright, poet, musician and fiction writer. His latest work is Daruma Tales, stories of the Japanese Canadian internment. Bukkyo Tozen, a history of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism in Canada 1905–1985, is his most ambitious project. He also edited Collected Voices, an anthology of Asian North American periodical writing. (Photo courtesy Harry Yonekura)

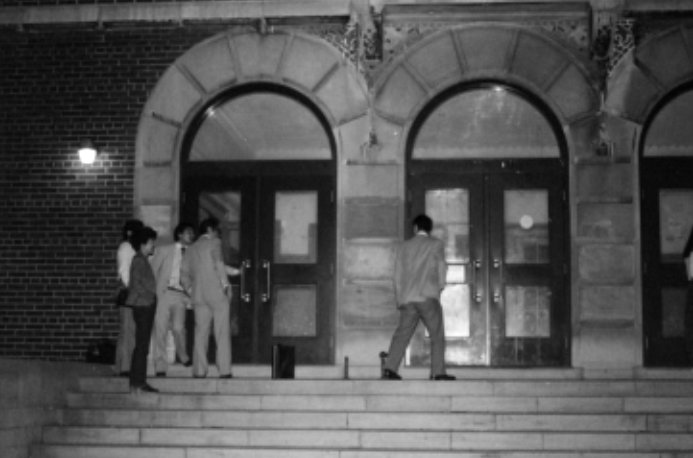

HARBORD COLLEGIATE, at 286 Harbord St. in west-end Toronto, was the site of a heated public meeting on July 19, 1984. (Photo: Harry Yonekura)

Shirley Yamada and other members of “Concerned Nisei and Sansei” entering Harbord Collegiate. (Photo: Stan Hiraki)

DR. WES FUJIWARA was born in 1919 in Sydney, B.C. and grew up in New Westminster and Vancouver. He came to Toronto to study medicine at U of T during the war years. Thus, he missed the expulsion and internment. While studying in Toronto, he developed a friendship with Rev. James Finlay of the Carlton United Church and with his help brought his sister Muriel Kitagawa and her family to Toronto from B.C. After completing his courses in medicine, Wes interned in Saskatchewan and Iowa City before returning to Toronto. He married Misao Yoneyama in 1950. Wes became involved in Redress from the very outset, shortly after the Sodan Kai held its initial public meeting at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto. Throughout the five year struggle and sometimes bitter conflict in the Toronto J.C. community, Wes stood out as one of the prominent leaders, never afraid to voice his support of the NAJC. Despite his busy pediatric practice, he always managed to squeeze in time for the Redress fight.

DR. MISAO YONEYAMA was born in 1915 in Vancouver and grew up in Haney, B.C. She has been a wonderful role model for Japanese Canadian girls for many decades, for she became a doctor during a period when a career in medicine was not very common for any woman, regardless of her race. Faced with sexism and racism, she wrote to every university with a faculty of medicine until she was finally accepted at the University of Alberta. After completing her studies there, she interned at the Women’s College Hospital in Toronto. In an article that she wrote for Nikkei Voice (April 1988), Misao recalls that at first she was afraid that she couldn’t “build a practice in a prejudiced city like Toronto”, especially after another female doctor took her aside and suggested that she change her name “so that it did not sound ‘Japanese-y’.” But in time, Misao gained acceptance and respect in the field of obstetrics. She delivered thousands of babies during her practice, and went without sleep for days on end. Although her practice was very strenuous, Misao, together with her husband, Wes, hosted numerous Redress meetings at their home in North York. (Photo: Vancouver Bulletin)

Left to right: Harry Yonekura, Roger Obata and Doug Bowie, an official from the Ministry of Multiculturalism and Citizenship in Ottawa, fall 1984.. Below, left to right, Wes Fujiwara, Sergio Marchi, Roger Obata, Bill Kobayashi, Harry Yonekura and Kunio Hidaka at the same meeting arranged by Doug Bowie. (Photos: Matt Matsui)