Chapter 5

Sodan Kai

By Roy Ito

Sodan Kai appear’ed on the scene in 1983 when three Toronto lawyers—Shin Imai, Maryka Omatsu and Marcia Matsui—began to gather fellow Japanese Canadians together to discuss the lack of community involvement in the Redress issue. All three of these young JC lawyers were either relatively recent members of the Ontario Bar Association or about to be. Japan-born but Canadian-raised Imai (no relation to George Imai) and sansei Omatsu specialized in human rights law and sansei Matsui in criminal law.

Until Sodan Kai was launched, there had been no public attempts to get input on Redress from the Japanese Canadian community, despite the fact that the issue was heating up south of the border. These three lawyers had studied the case for Redress in the United States and were aware of the fact that in 1980 the U.S. Congress had established a Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians—and that in February 1983 the Commission had submitted a report, Personal Justice Denied, recommending a public apology and individual compensation. Why were the various Redress options and legalities still relatively unknown in the Japanese Canadian community? It was time to start spreading the information.

By the fall of 1983, Sodan Kai had established a monthly newsletter, Redress News,1 and had expanded its membership to include several other sansei and nisei who believed in informing and listening to as many Japanese Canadians as possible so that any position taken to the Canadian government would be arrived at democratically. Along with Shin Imai, Marcia Matsui and Maryka Omatsu, the core group of founding members included Connie Sugiyama (a corporate lawyer), Jesse Nishihata, Ron Shimizu, David Fujino, Joanne Sugiyama, Jim Matsui, Joy Kogawa, Roger Obata and Frank Moritsugu. Also involved during those early years were Edy Goto, Henry Sugiyama, Betty Moritsugu and Ben Fiber, a Globe and Mail writer and friend of Joy Kogawa.

It was Shin Imai who dreamed up the name “Sodan Kai" which is comprised of kanji (a system of Japanese writing using Chinese characters) that together signify “arriving at a mutual decision through quiet group discussion". Shin Imai described it as “a diverse group of nisei and sansei with different backgrounds, different interests, and different views on what form redress should take." What united the members was the belief that “Japanese Canadians should be given information on Redress, and provided with a forum for discussion of the issue before an official position is presented to the government, or to Canadians as a whole.”2

What began as informal discussions in each other’s homes soon grew into public meetings, educational forums and a major movement that posed a challenge to those in the community who wanted to strike a quick deal with the government. The goal of the organization was not to push for any particular position or usurp power from anyone, but simply to flush the entire issue into the open.

The development that snapped the Sodan Kai from an informal discussion group into a recognized community action group was the announcement in March 1983 that the Japanese Canadian community would seek a $50 million trust fund from the government to set up programs to promote racial harmony and human rights. This announcement seemed to come out of thin air as many JCs learned about it for the first time from newspaper reports. Decisions were being made without consulting the community. As one former Sodan Kai member, a nisei writer, put it: “Hey, hold on. Who is this speaking for me? Who asked me how I feel? Or what I want…I got a bad feeling. A feeling not too different from the feeling I felt in 1942… The bad feeling that somebody else, without asking me, is deciding in my name and the names of all the other JCs what to say to Ottawa about a question that concerns all of us… Surely doing things democratically is what being a Canadian is about.”3

Sodan Kai’s First Public Meetings

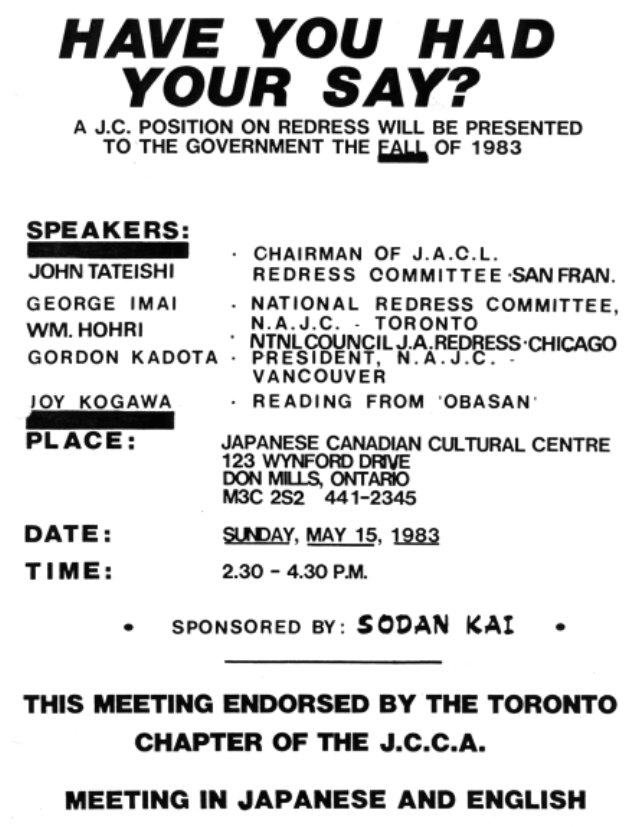

The Sodan Kai decided to hold its first public meeting on May 15, 1983. It was an ambitious undertaking. A few months earlier Marcia Matsui, Maryka Omatsu and Ron Shimizu (substituting for Shin Imai) approached George Imai, chairman of the National Redress Committee and president of the Toronto Japanese Canadian Citizens Association. to learn more about the reported community fund proposal to the government—and to ask him to endorse a public meeting to get more input on the matter. According to the Sodan Kai representatives, George Imai’s initial reaction was that getting more and more people involved “would be too messy”. Astonished and disturbed by his reaction, they decided to continue pushing for a public meeting and he finally agreed to endorse it on the understanding that the Sodan Kai would remain neutral on the direction of Redress.

There was an amazing turnout of over 300 people on that Sunday afternoon, May 15, 1983 at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC) on Wynford Drive.4 The huge turnout could be attributed to the stories that the Sodan Kai had submitted to the JC newspapers, the photocopied invitations sent to select persons and hand-made signs posted at such places as Furuya Trading Co. and other locations frequented by Japanese Canadians.

Taking part in the panel discussion were NAJC president Gordon Kadota from Vancouver, George Imai, chairman of the National Redress Committee, and two Japanese American representatives—William Hohri of the National Council for Japanese American Redress, and John Tateishi of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). As in Canada, the two American groups were not in agreement with each other. While they both agreed that individual compensation was warranted, they differed vastly in terms of strategies. The audience could feel the strain between Tateishi and Hohri, the latter being distinctly more militant than the JACL representative.

The meeting, scheduled to take place from 2:30 to 4:30, lasted four hours and became an unexpected turning point in the Redress struggle. By the time it ended, there were still about 100 people in the room who were willing to hear more. It was significant because it not only generated debate, but also much needed funds. The generosity of donations given by those at the May 15, 1983 meeting helped build up the Sodan Kai fund for future mailings and other administrative costs. Until then, the members absorbed all the costs.

Another memorable aspect of the first Sodan Kai public meeting was the fact that a decision was made by those present to design and distribute a questionnaire to give as many people as possible a chance to express their views on Redress. By mid-June 1983, the questionnaires had been distributed by mail and at church gatherings, community picnics, issei clubs and local Japanese restaurants.

Finally, the May 15 meeting was important because it enabled a large number of Japanese Canadians to see and hear from George Imai for the first time. Before the meeting he was just a name in JC community newspapers. Several people at the JCCC that afternoon have attested to the fact that George Imai seemed to avoid answering any questions directly. According to one former Sodan Kai member, the impression that he made of not being very communicative was a premonition of the rocky road ahead in the Redress campaign.

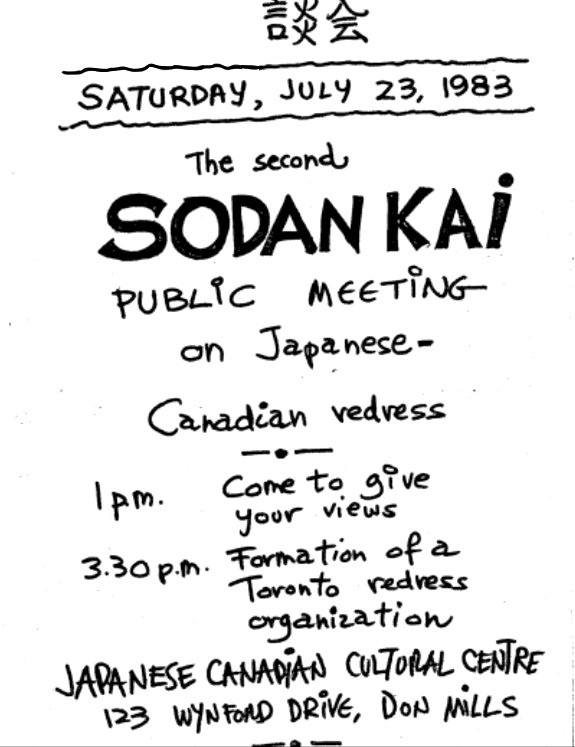

The second Sodan Kai “have you had your say” meeting took place on Saturday, July 23, 1983, with Shin Imai and Frank Moritsugu acting as chairmen. This gathering was considerably smaller than the one in May. Only about 120 people came out to hear the opinions of their fellow community members. This time there were no official guest speakers. Instead Shin and Frank attempted to get the attendees to express their thoughts and feelings on Redress. Both Japanese and English were used to encourage the issei to take part fully.

The various views expressed that afternoon were eye opening. A vote revealed that those present were in favour of some sort of Redress, a government apology and financial compensation, but there was not enough time to begin exploring the heavy issue of individual versus group compensation. The Sodan Kai promised to hold another meeting devoted to that debate.

The second part of the July 23 meeting, with the cooperation of the Toronto JCCA, dealt with organization. A motion was passed for the Sodan Kai and the Toronto JCCA to form a separate Toronto Redress group. The official name of this new organization would be determined later.

Following the July meeting, blistering attacks against the Sodan Kai appeared in the Toronto based, JC community newspapers. It had never been the intention of the Sodan Kai to compete in any way with existing organizations, yet the members were obviously viewed as some kind of threat to the political power of certain community leaders. A particular writer named “Mark Suzuki” (a pseudonym for an unidentified JC) wrote articles in support of George Imai and in condemnation of the Sodan Kai for allegedly taking over. Shizuye Takashima, noted JC artist and author of A Child in Prison Camp, was another person who accused the Sodan Kai of usurping the role and responsibilities of the Toronto JCCA. She questioned why it was necessary to form a Toronto Redress group when the city was already represented at the National Council through the National Redress Committee and the Toronto JCCA.

1983 Labour Day Conference at Prince Hotel

The next major event in the history of Sodan Kai was the Labour Day conference at the Prince Hotel. Labelled as a “Redress PreConference”, this gathering included delegates from across the country who met to formulate a plan for Redress negotiation. The Sodan Kai and a group from Vancouver, the Japanese Canadian Centennial Project (JCCP) Redress Committee, argued for and received official voting status.5

The September 2-4 conference was a powerful event. After considerable and loud discussion, another controversial motion was passed. It was decided to create a new body of the NAJC: a 15 member National Redress Council which would represent JC centres across the country and which would have overriding jurisdiction over any existing Redress committees, national or local. Thus, George Imai’s status as a Redress “spokesperson”, was greatly diminished. Along with two of his supporters, Imai resigned and walked out of the meeting, angered by what was in effect a vote of non-confidence. Three other representatives—Jay Hunter from Kelowna, Mas Kawanami from Calgary and Vic Ogura from Montreal—also left the meeting in protest.

The entire proceeding was clearly a resounding vote of nonconfidence in the leadership of the National Redress Committee. Therefore, when George Imai walked out, his resignation should have been accepted as a logical conclusion. However, following an impassioned plea from Kinzie Tanaka, a long time member of the JCCA, President Kadota and Tanaka were asked to approach George Imai to reconsider his resignation.

Then on September 9, 1983 Gordon Kadota received a letter from George Imai withdrawing his resignation. Copies of it were sent to all NAJC centres across Canada. Apparently, George Imai had had a change of heart. The JCCP Redress Committee and the Sodan Kai were later accused in the JC community press of attempting to restrict the power of the National Redress Committee by orchestrating a “powerplay”.

According to some of the articles that appeared, the Sodan Kai was no longer neutral. The Canada Times reported the following: “Accepted rules of procedure were shunted aside and normal parliamentary practice was changed illegally at the meeting—just to accommodate pressure groups, like Sodan and JCCP, which have little or no established bases of representation in the Japanese Canadian community.”6 The same article argued that giving voting rights to the two newly formed groups was illegal because major changes in policy, such as voting privileges, had to be made at official national conferences. Similarly, the creation of the National Redress Council was also viewed as being illegal.

George Imai told a Globe and Mail reporter that “As far as Redress is concerned, everything has come to a halt. We now have certain groups trying to stop or delay negotiations which they have effectively done.”7 Although he did not mention the name of the groups, one can safely assume that he considered Sodan Kai one of the groups responsible for bringing negotiations to a halt.

Sodan Kai delegates at the Prince Hotel Conference were intelligent and knowledgeable people. They understood the rules of parliamentary procedure, but they felt that they had no choice but to ask for voting status because of the inaction of the Toronto JCCA and the National Redress Committee, both dominated by George Imai. The priority of the Sodan Kai was still to ensure that any decisions on Redress strategies and proposals be arrived at through consensus and that all Canadians of Japanese ancestry should have a say.

Through Shin Imai, the Sodan Kai issued a clarification statement that was published in The New Canadian. He wrote: “We deeply regret the controversy that has surrounded the Labour Day meeting [at the Prince Hotel]. We have tried to avoid engaging in the controversy because it would detract from the real issue of arriving at an informal common position on Redress…” The statement continued, “To the extent that there are differences in opinion, we feel that they can be resolved within the community without exposing our disagreements to the scrutiny of Canadians as a whole… The issue of Redress is very much alive. And the differences that have arisen are those expected within a community made up of thousands of interested Japanese Canadians.”8

The Sodan Kai’s third public meeting on Redress was held on Sunday, October 23 at the JCCC. A major part of the meeting was devoted to a spirited, 3½ hour discussion of group versus individual compensation, followed by a vote. About 50 called for individual compensation. About 20 voted for group compensation, and another 24 favoured a combination of the two. It should be noted that by prior agreement Sodan Kai members did not express their personal views on the subject of group versus individual Redress. They announced at the outset that they would refrain from participating in the actual debate so that other speakers would not be influenced by them.

At the beginning of the meeting, George Imai, supported by five other speakers, suggested that a discussion about the organizational conflicts be held first, rather than a discussion on various Redress options as originally scheduled. After an exhausting discussion from the floor, George Imai’s suggestion was defeated by a vote of 74 to 39. It was like another slap in the face for him.

The October 23 meeting also included a special tribute to the late Andrew Brewin who died in B.C. in September 1983. Co-chairman Frank Moritsugu described Mr. Brewin as an important Canadian who had worked valiantly for Japanese Canadian civil rights because of his strong belief that Canada’s tradition of civil liberties for everyone was being violated.

Another departure from the usual proceedings was the first public performance in Toronto of a recently formed nisei harmonica group. The members of the group included Noji Murase, Juni Ikeno, George Tsushima, Ken Sugamori and Frank Usami.

Moritsugu recalls that “time did not permit a detailed discussion of other Redress options”, but later “Dr. Art Shimizu of Hamilton spoke in some detail about the [War Measure] Act”, urging the JC community to go “on record against the injustices it can perpetrate…”9 Moritsugu also remembers that when the meeting ended, “the Sodan Kai members attempted to set up a second meeting right then and there for a discussion of the organizational questions George Imai wished to raise earlier. However Mr. Imai advised the meeting he was unable to stay because of a supper engagement.”10 Thus the second meeting did not take place.

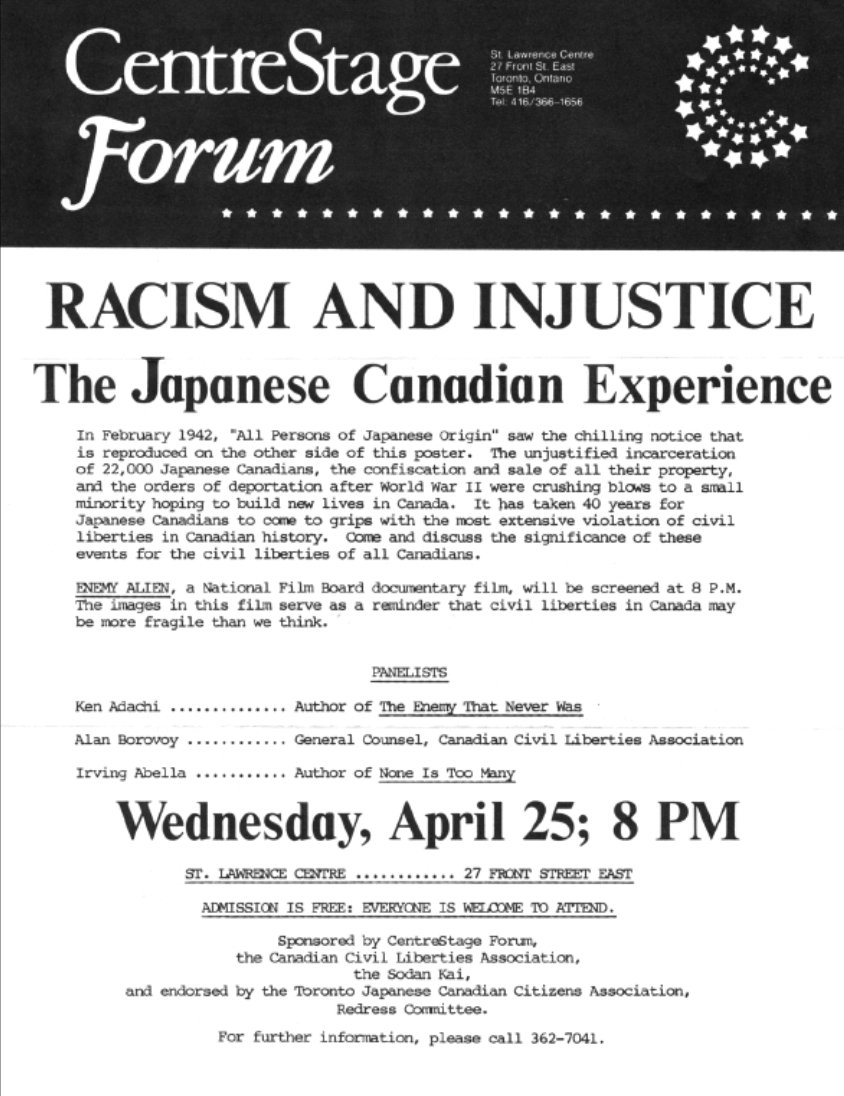

CentreStage Forum, April 25, 1984

Sodan Kai succeeded in getting the Redress issue into the media spotlight and igniting debate. One of the first attempts to extend the issue outside the Japanese community was a public educational forum held in Toronto at the CentreStage Forum of the St. Lawrence Centre on Front Street. Aptly titled, “Racism and Injustice: The Japanese Canadian Experience”, this forum took place on the evening of April 25, 1984, shortly after Prime Minister Trudeau’s inflammatory statements in the House of Commons.11 The panel consisted of NAJC national president, Art Miki, Alan Borovoy of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, Irving Abella, a prominent history professor at Toronto’s York University and Ken Adachi, author of The Enemy That Never Was.12 Not far off-stage were the forum’s key organizers: Marcia Matsui, Shin Imai and Maryka Omatsu.

An audience of about 450, comprised of both Japanese Canadians and non-Japanese Canadians, listened intently as panelist after panelist attacked Trudeau’s “the past is the past” dismissal of our Redress claims. Each speaker emphasized the fact that the JC Redress issue did not concern only Japanese Canadians. It was a human rights issue, a legal issue that affected all Canadians.

Ken Adachi posed the question, “How should Canadians respond to what the Parliamentary Committee on Visible Minorities has characterized as one of the most sordid chapters in Canadian history?” Adachi provided the audience with two straightforward responses to the question—two seemingly obvious moral imperatives. “first, those who unjustly lose their liberty at the hands of the government require an apology [and] second, they are entitled to compensation from that government.” He added that words alone were insufficient. “Not until Parliament makes such a statement and backs it up with more than crocodile tears, will any apology be meaningful.”13

Irving Abella declared that it was his obligation to participate in the forum because the Redress issue “is one that involves all Canadians.” He continued: “When the rights of one group of Canadians is taken away, then all Canadians suffer… Japanese Canadians may have been freed from their internment in 1945, but Canadian society will not be released from its spiritual internment until it can come to terms with the injustice that it perpetrated on fellow Canadians some 40 years ago.”14

Alan Borovoy echoed Irving Abella, telling the audience not to be discouraged by Trudeau’s stance. In fact, he predicted that Trudeau’s remarks would ironically become the “blessing in disguise”. He reminded us that the wise political activists “have told us for many years that we’re galvanized into action, much less by our competent allies than by our dubious adversaries.” The emotional fervour in the audience grew as Borovoy’s voice rose. “Now is the time,” he urged, “to build strong, vibrant organizations that are prepared to fight like hell for their members!”15

As a public education event, the CentreStage Forum went far in exploring various aspects of the Redress issue. It was followed up over the next year or more with workshops for high school students. Cosponsored by the Toronto NAJC and the Toronto Board of Education, these workshops were designed and led by Ken Noma and Sodan Kai members such as Ron Shimizu, Shin Imai, Maryka Omatsu and Marcia Matsui. They provided young people with unique insights into chapters of Canadian history that had been chiefly ignored in Canadian classrooms up until the 1980s. Divided up into seminar groups, students participated in role playing activities to explore such issues as anti-Asian discrimination, the history of the expulsion and internment, the struggle for Redress and civil and constitutional rights. For example, participants, pretending to be politicians, took part in an imaginary meeting to decide how the government should act towards the Japanese Canadians after the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The Impact of the Sodan Kai

Shortly after the St. Lawrence Centre forum, the Sodan Kai went out of active existence since it had accomplished its goal of getting the discussion going, educating the public and creating a more democratic decision making process with regard to the Redress campaign. Also, by the spring of 1984, the North York chapter of NAJC was formed, alleviating the Sodan Kai from the responsibility of educating the public about the latest Redress developments. The North York chapter soon changed its name officially to the NAJC, Greater Toronto Chapter and became the authoritative voice of Redress for Toronto area Canadians of Japanese ancestry.

Although no meetings were held for almost three years, the Sodan Kai existed on paper until 1987. It was not formally dissolved until December 1987. Treasurer Joanne Sugiyama met with Frank Moritsugu and “in the absence of any other active members decided that the final balance left of mainly donated funds, that is, $393.11, would be donated to the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre since it had provided us with a rent-free venue for our [public] meetings.”16 A portion of the remaining balance was also donated to the local chapter of the NAJC.

Looking back on the whole Sodan Kai experience, one can say that Sodan Kai was instrumental in getting the issue out into the public spotlight and democratizing the Redress movement in Toronto. Privately, the individual members all had strong opinions, but, publicly, they managed to maintain a neutral face, reporting on the various Redress related events in Sodan Kai’s newsletter, Redress News, without commentary. After Sodan Kai faded out of existence, however, some of its members decided to take a more political direction by getting involved in the Toronto NAJC. Former Sodan Kai members Roger Obata and Maryka Omatsu eventually became members of the National NAJC’s Redress Strategy Committee.

When asked to recall her Sodan Kai experience, Connie Sugiyama states: “I remember there was some anger—some of it intentionally focused on the fact that we were largely sansei. That we were young rabble rousers who didn’t understand either the community or the issue and that really it wasn’t our business.” Sugiyama adds that … “there was a lot of sniping in the press and…I think everybody in the Sodan Kai at one time or another got attacked for different reasons…It was an exhausting, painful, disillusioning experience and very confusing because…we never knew whether to react or try to be pro-active and I think it was difficult to sort out the legal issues, the political issues, the emotional issues. I just sort of got worn out." Nonetheless, Connie Sugiyama sees the public meetings organized by the Sodan Kai as “defining moments in the history of the JC community.”

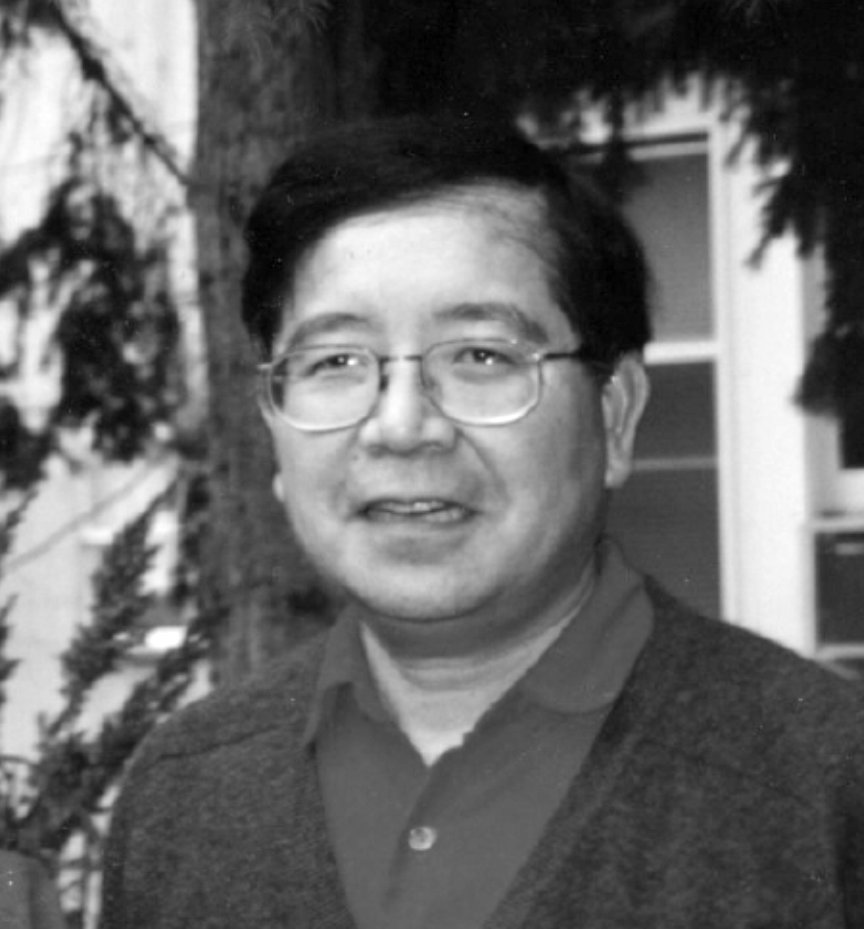

SHIN IMAI was born in Tokyo in 1950. He came to Canada in 1953 with parents, Yachio Imai and Ken Imai, former minister of Toronto’s St. Andrew’s Japanese Anglican Church. While in law school, Shin became involved in the Redress movement when he was asked to prepare briefs for the National JCCA Human Rights Committee. Together with fellow JC lawyers Maryka Omatsu and Marcia Matsui he founded the Sodan Kai and gave the group its name. Presently on the faculty of Osgoode Hall Law School, he teaches poverty law and Aboriginal law. Shin looks back fondly on his Sodan Kai years, stating, “I’m very proud that so many Japanese Canadians have continued to fight for the human rights of other communities.” (Photo: Courtesy Shin Imai)

MARYKA OMATSU, daughter of Denno Omatsu and Satsuko Takishita, is Canada’s first Japanese Canadian woman judge. While practising environmental law, she was appointed to the Ontario Court of Justice (Provincial Division) in February 1993. Born and raised in Hamilton, Ontario, she became a founding member of Sodan Kai during the early days of her legal career. Before her appointment to the bench, she was chair of the Ontario Human Rights Board of Inquiry, an Ontario Law Society referee and a member of the women’s issues working group of the Ontario Fair Tax Commission. A key figure on the NAJC’S Redress negotiating team, Judge Omatsu has written movingly about the Redress victory in an award winning book, Bittersweet Passage (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1992). (Photo: John Flanders)

CONNIE SUGIYAMA became involved in Sodan Kai soon after its formation. She continues to be an active member in the Japanese Canadian community while at the same time carrying on a busy career in corporate finance and securities law. She is a director of the Japan Society, the Nikko Securities Company Canada Ltd., the Trillium Foundation and the Hummingbird Centre for the Performing Arts and special advisor for the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre and Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation. Connie is currently a partner of both Fasken Campbell Godfrey and the interprovincial and international firm, Fasken Martineau. She is proud of her involvement in the Sodan Kai, stating: “I certainly seek no credit or acknowledgement for any role I may have played in it. I became a member out of a sense of outrage as a Canadian at what the government was proposing to do without any meaningful consultation with our community.” (Photo courtesy Connie Sugiyama)

MARCIA MATSUI, the eldest of the two children of Matt and Nobuko Matsui, was born in 1949 in Toronto. Both Marcia and her brother, Jim, were very active in the Redress movement during the early stages of the campaign. Jim edited the first Redress News and Marcia was a founding member of Sodan Kai. She graduated from Osgoode Hall Law School in 1982, and was called to the Bar of Ontario in 1984. During 1984 1991 she practised criminal law and became a partner at the firm of Ruby and Edward in Toronto. During 1991-1994 she served as a political advisor to Premier Bob Rae (re constitutional and intergovernmental affairs). Currently, she has private practice in Stratford, Ontario. (Photo courtesy Marcia Matsui)

MASATOSHI RONALD SHIMIZU was born in 1944, at a Slocan internment camp. Ron is the youngest child of the late Toshiro Shimizu and Mita (nee Ozaki) Shimizu, who had settled in Ucluelet, B.C. in the pre-World War II years. After the war, the family moved to Hamilton, Ontario where Ron went to elementary school, high school and McMaster University. He received an Honours B.A. in political science in 1968 and an M.A. in political science in 1972. Ron was soon hired by the federal Ministry of the Environment where he pursued a career in water resource management. He is currently the Regional Director of the Environmental Protection Branch.

In 1976-77, Ron served on the Board of Directors of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto and organized the JC Centennial Youth Conference. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, He and his wife, Edy Goto, became founding members of the JCCC Annex and active members of the emerging Redress movement. Ron also sat on the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee and was active in Sodan Kai and later in the Toronto chapter of the NAJC. Today he and Edy live in Toronto with their two children, Aja and Tomo.

In talking about his father, Ron states, “My dad didn’t talk much about the war years so I learned about it from my older brothers and sisters, two of whom were community leaders in the Redress movement in Hamilton and Victoria. I was bowled over when one day I asked my dad why he wouldn’t visit one of my brothers who was living in Ottawa. He said that he would never step foot in the capital for what the government did to him and the family. I realized then how deeply affected and profoundly scarred he had been by this terrible injustice. He had been waging his own campaign for justice in silent protest for all my adult life and had not told us. Dad was 98 when he received his apology a few month before his death.” (Photo courtesy Ron Shimizu)

Protest button sold for one dollar during the Redress campaign.

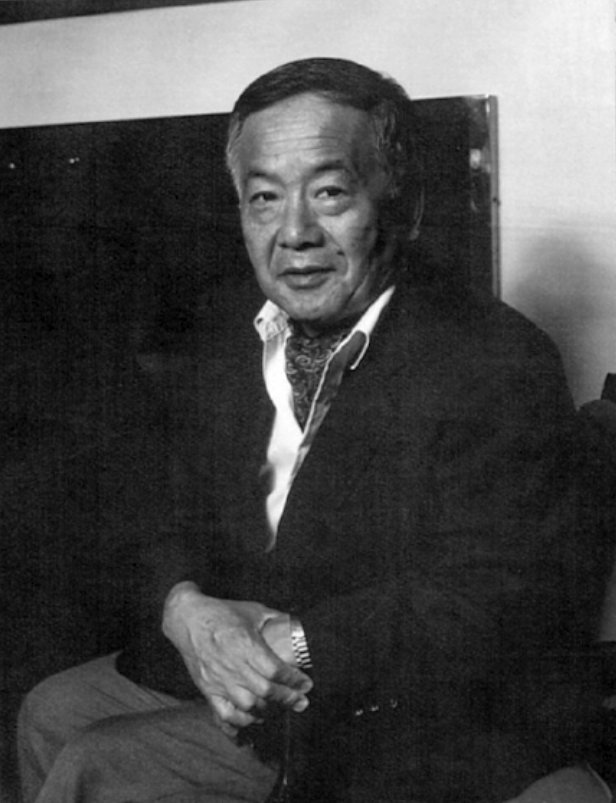

FRANK MORITSUGU was born in Port Alice, B.C. In 1942 he was sent to Yard Creek road camp near Revelstoke, B.C. and in 1944 he moved to Ontario. He began his career in journalism as a staff member of The New Canadian. After serving with the Canadian Army in India, he pursued his interest in journalism at the University of Toronto where he was editor of The Varsity, the campus newspaper. Frank has been on the staff of Maclean’s, The Toronto Star and The Montreal Star. He has also worked as the communications director for various government ministries and as a journalism teacher at Centennial College in Toronto. He is currently publisher and columnist of Nikkei Voice. On Redress: “I started out in 1983 thinking an apology would be sufficient without monetary compensation, not because it was shameful to ask for compensation but because I didn’t feel that an appropriate amount could be determined. As I took part in the 1983 Sodan Kai meetings, my thoughts changed…a politician’s apology, even by the Prime Minister, can be shrugged off too easily by our jaded Canadian society.” (Photo courtesy Frank Moritsugu)

Notes

1 Jim Matsui did almost all the work producing five issues of Redress News. He used his own funds. Others, including Marjorie Hiraki, donated time, money and effort as well.

2 Imai, Shin. “Statement of the Sodan Kai”, The Canada Times, October 25, 1983.

3 Unpublished notes by a former Sodan Kai member who would rather remain anonymous.

4 Toronto’s JCCC allowed the Sodan Kai to hold this and two other subsequent public meetings there because the meetings were “non-political” in the government sense. The Centre’s non-profit charitable organization tax status does not allow “political gatherings”.

5 The Vancouver based JCCP published A Dream of Riches in 1981, a book of photographs depicting JC history, to mark the 1977 JC Centennial. A JCCP Redress Committee was later formed to educate Japanese Canadians and other Canadians about Redress.

6 “National Redress Committee Withdraws Resignations”. The Canada Times, September 16, 1983.

7 The Globe and Mail, September 14, 1983.

8 Imai, Shin. The New Canadian, October 18, 1983.

9 Moritsugu, Frank. Unpublished report of Sodan Kai meeting, October 23, 1983, p. 4. (Based on notes taken by the recorder, Connie Sugiyama, and by the co-chairmen, Shin Imai, and Frank Moritsugu.)

10 Ibid., p. 5.

11 In April 1984, when pressed by NDP MP Lynn McDonald and Ed Broadbent to respond to the JC Redress question, Prime Minister Trudeau declared that the past could not be rewritten and that his government would not be apologizing for the mistakes of his predecessors.

12 The late Ken Adachi’s book, first published in 1976, is still regarded as one of the most reliable and compelling sources of information on Japanese Canadian history.

13 Adachi, Ken. [speech]. April 25, 1984. Delivered at the Sodan Kai sponsored forum, “Racism and Injustice: The Japanese Canadian Experience”, CentreStage Forum, St. Lawrence Centre, Toronto, Ontario.

14 Abella, Irving. [speech]. April 25, 1984, CentreStage Forum, Toronto.

15 Borovoy, Alan. [speech]. Ibid.

16 Moritsugu, Frank. Unpublished notes prepared at the request of Roy Ito, May 12, 1998.