Chapter 7

Trudeau Says “No”

By Roy Ito

Lynn McDonald, the NDP Member of Parliament for Broadview-Greenwood, stood up in the House of Commons on April 2, 1984 and asked Prime Minister Trudeau to respond to the unanimous recommendations of the Special Committee on Visible Minorities with regard to Redress for Japanese Canadians, stating, “Will the Prime Minister undertake to introduce a resolution with regard to the acknowledgement of the wrongdoings, the re-examination of the War Measures Act, and the beginning of negotiations with representatives of the Japanese Canadian community?”1

After announcing that he had not yet read the report and that any decision would be a matter for the Cabinet to decide, Trudeau launched into his honest, personal opinion on the matter of an apology and compensation:

If the Honourable Member is interested in my personal opinion, which is open to the possibility of change after reading the report and hearing the arguments, I am not inclined to envisage questions of compensation for acts which have perhaps discoloured our history in the past, if other means of redress are possible. I am not quite sure where we could stop the compensating. I know that we would have to go back a great length of time in history and look at all of the injustices which have occurred, perhaps beginning with the deportations of the Acadians and going on to the treatment of the Chinese Canadians in the late 19th century. I do not believe in attempting to rewrite history in this way.

On other occasions I have personally expressed to Japanese Canadians the regret that I feel about the terrible acts which happened to them. There is no justification for them after the fact. To me, this is in the category of those who want to rehabilitate Riel. Riel stands as he stands. I do not see that there is much to gain by trying to apologize for acts of our greatgrandfathers and their great-grandfathers.2

Two days after Trudeau’s controversial remarks in the House of Commons, Ed Broadbent, leader of the NDP, pressed Trudeau to make a commitment to pursue the issue of Redress for Japanese Canadians. Broadbent made the important point that the people who suffered the injustices inflicted by the government of Canada were still very much alive, not ancient ancestors. He stated,

“On Monday the Prime Minster said, I hope in a premature way, that he was expressing the personal view that it would be inappropriate to redress wrongs that were inflicted upon our ancestors. Considering the people who are being discussed are not simply ancestors—more than one half of them are still alive today, considering the injustices are real and that the Government of Canada should do something about them, I would now like to ask the Prime Minister if he would, not personally, but on behalf of the Government, say, first, that there were injustices inflicted upon Japanese Canadians…and second, will he commit the Government to some compensation for such past injustices.”3

Trudeau’s response to Broadbent was basically the same as his response to Lynn McDonald two days earlier. According to Trudeau, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms attached to the Constitution would prevent such an injustice from happening in the present and in the future. Later in the course of the same debate, he added, “…Government’s main function is to be just in its time. It is not to try to correct the injustices that have been done to everybody in the past.”4

Trudeau’s remarks in the House of Commons during those two days in April 1984 ironically proved to be the fuel that the Toronto Redress activists needed in order to get the Japanese Canadian community mobilized for the struggle. His words were an enormous insult and an outrage that ended up creating a wave of reaction across Canada.

In his matter-of-fact tone, Trudeau made no attempt to camouflage or soften his position. There would be no apology, no compensation for Japanese Canadians. According to Trudeau, the door to compensation closed over 30 years earlier with the Bird Commission findings. The past could not be rewritten and the noble Charter of Rights could not be applied retroactively.

By drawing an analogy between our case for Redress and recent attempts to pardon Louis Riel (who was hanged for treason in 1885 for trying to regain land in Saskatchewan which the Métis regarded as their legal property), Trudeau, the famous founder of the “just society”, exposed his blatant fallacious reasoning. He demonstrated his callous disregard for any notion of justice even further when he tried to compare our situation to that of the 6,000 to 7,000 Acadians who were expelled from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in the 1750s for refusing to swear an oath of unconditional loyalty to the government of England after England’s war with France. His implication was that if the government compensated the Japanese Canadians, then the descendants of the expelled Acadians might come knocking on his door asking for compensation one day. He did not want to set a precedent.

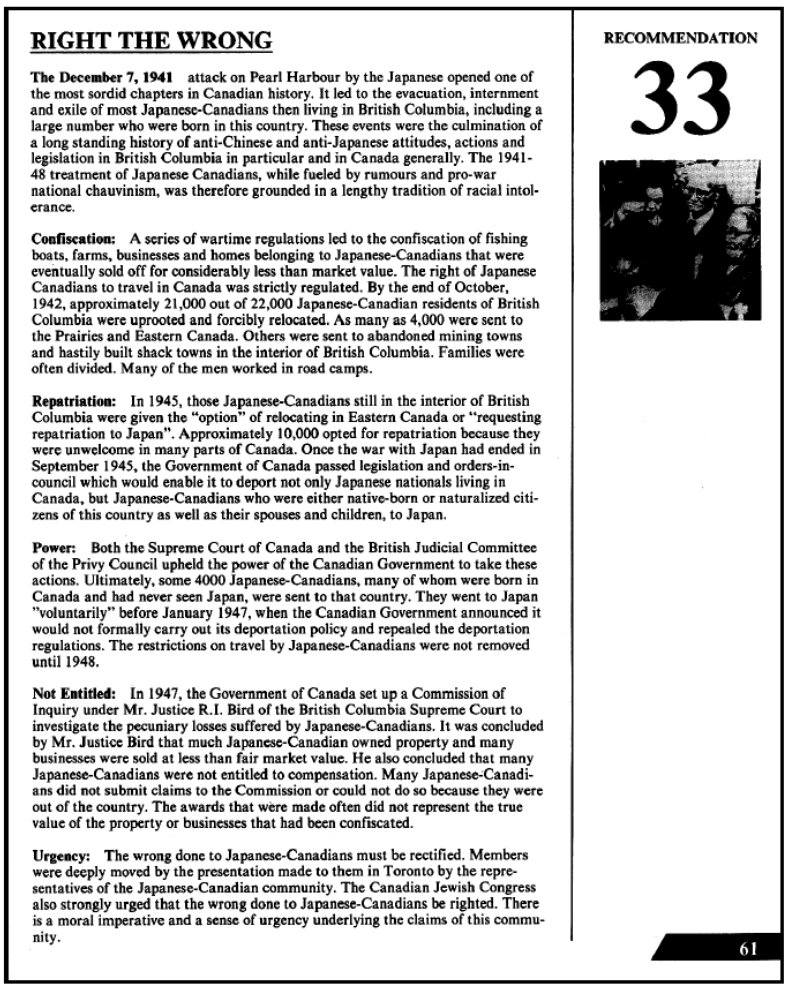

Armed with Equality Now!

Juxtaposed to Trudeau’s view of our history was the clear recommendation of the Special Committee on Visible Minorities in Canadian Society, a committee commissioned by the House of Commons in June 1983. In its report, Equality Now! (March, 1984), the Special Committee spelled out the entire argument for Redress logically and succinctly within two pages. The basic point that came across loud and clear was that the “wrong done to Japanese Canadians must be rectified…There is a moral imperative and a sense of urgency underlying the claims of this community.”5

The Redress movement across Canada was bolstered by the recommendations in Equality Now! These recommendations were coming not from the Japanese Canadian community, but directly from a House of Commons committee. In light of this report, the press easily shot down Trudeau’s flawed reasoning and our cause received considerable attention in the mainstream press. In general, the articles and letters to the editor in Toronto newspapers were critical of his stance, except for the illogical letters from World War II veterans who could not help harping on the brutal treatment of Canadian soldiers in Japanese prisoner of war camps. These veterans could not make any distinction in their minds between a Canadian citizen of Japanese ancestry and a World War II soldier from the Japanese Army.

The Toronto Star commented: “It’s sheer sophistry to argue, as Prime Minister Trudeau did this week, that in the case of the Japanese Canadians…there is little point in trying to apologize for acts of our great-grandfathers and their great-grandfathers. Some 11,000 Japanese Canadians, victims of persecution, are still alive today. It’s not a matter of apologizing to the dead…but of meeting the grievance of living Canadians…”6

The Globe and Mail headlined their story “PM Cool to Compensating Interned Japanese”.7 I remember that this particular wording angered many members of our community here in Toronto because of the omission of the word “Canadian” after the word “Japanese”. A more accurate and acceptable headline would have read, “PM Cool to Compensating Interned Canadian Citizens.” An indignant Mary Obata promptly wrote to The Globe and Mail, pointing out the error: “Canadians, no matter of what origin, should be called Canadians. You did a great disservice to Canadians of Japanese descent in your headline…The headline was instantly prejudicial to the matters discussed…Ours is a land of many origins, but a Canadian is a Canadian first.”8

The next day, The Globe and Mail published an editorial that tore away at Trudeau’s arguments, reiterating the fact that the compensation issue was not about ancestors, but survivors: “there are men and women, younger than Mr. Trudeau who were victims…and who are very much alive in Canada in 1984. Whatever form the compensation takes, it should not be derailed by Mr. Trudeau’s curious notion of where history ends and current affairs begin.”9

Trudeau’s remarks about Riel and the Acadians were so preposterous that numerous letters to the editor, from Canadians of various walks of life, appeared in the daily press. Many readers mentioned that Japanese Canadians were not involved in a rebellion like Riel, nor were they accused of any sort of disloyalty as the Acadians were. The proof of patriotism was the fact that many nisei, from the day war was declared against Germany, had attempted to volunteer for the Canadian Armed Forces, but had been rejected on racial grounds. It wasn’t until March 1945 that they were finally permitted to serve their country as Canadian citizens. After all the indignities that they faced at the hands of the Canadian government, several nisei still volunteered to take up arms against Japan while their families remained imprisoned in Canadian relocation camps. There was never any cause to doubt the Japanese Canadians’ devotion to Canada.

Sodan Kai founder, Shin Imai, wrote a cogently argued response to Trudeau in The Globe and Mail on April 16, 1984. In his article, he compared the situation of the Japanese Canadians to that of Donald Marshall, the Micmac of Nova Scotia who, at that time, had received an interim payment from the government for the 11 years he was imprisoned for a murder he did not commit, and he asks, “Why would Japanese Canadians be viewed differently? It is not because the internment was justified…Part of the reason for [Trudeau’s] chilly response may lie in the perception that the issue is dated. Yet there are more than 10,000 Japanese Canadians alive today who directly suffered. If there has been silence for almost 40 years, it has been the silence of victims who feel guilt and shame for their own victimization.” Further on in the same article, Shin Imai states, “This case illustrates the need for developing an effective remedy when there has been such a massive violation of civil liberties. It is a challenge Mr. Trudeaau would avoid. He would place these events in history texts and firmly close the covers.”10

A Shameful Exit from the Political Stage

The Opposition had a field day in the House of Commons after Trudeau’s ridiculous statements. Brian Mulroney, then the leader of the Progressive Conservative Party, entered a heated exchange with Trudeau and shouted that a Conservative government would surely compensate Japanese Canadians. The New Democrats—specifically Ian Waddell, Lynn McDonald, Ed Broadbent and Dan Heap—kept our cause alive in the House of Commons for a long time and were particularly relentless in their attacks on Trudeau.

Trudeau had a chance to save his reputation and retire from political life on a high note as a truly honourable politician who did the morally and legally correct thing, but he chose to remain intransigent on the question of Redress throughout his final days in office. After some prodding from the media and various organizations, the Liberal government finally showed some signs of movement on June 29, 1984, just ten days before John Turner took over as prime minister. The government announced that it would issue a formal apology to Canadians of Japanese ancestry, but only an apology and nothing more. There would be no financial compensation whatsoever for families whose properties were seized or whose members were interned. The only concession that the government offered was a proposal for a $5 million foundation to promote racial harmony in Canada. Although some members of our community, such as George Imai, advocated an acceptance of this hollow apology, most of the Japanese Canadians viewed it as an insult. Without any sort of individual compensation to go along with it, the apology was rendered meaningless.

We did not have to shout our disapproval. The media, almost speaking as one voice from coast to coast, condemned the Liberal government. The Globe and Mail reminded its readers that in 1969 Prime Minister Trudeau had said, “…in the long run a democracy is judged by the way the majority treats the minority.” Entitled “Of Sorrow and Shame”, this editorial continued with very harsh words for Trudeau: “As a final act of public service, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau had the opportunity to lead Canada in a noble act of atonement for its wartime persecution of Japanese Canadians. Instead, his government has turned this infamous page of Canadian history with a tepid gesture—an offer of regret without restitution…it cannot be considered Redress for Japanese Canadians who were deprived of their liberty and their land. They, and their survivors, can hardly be consoled. Their cry will continue to be: no confiscation without compensation.”11

The Toronto Star joined the cries of protest, calling the Liberals’ offer “scarcely half an apology” and “shabby tokenism” and attacking Trudeau for designating David Collenette, a junior member of his cabinet, to deliver the announcement of the apology on behalf of the government: “The utter inadequacy of Ottawa’s responses is apparent in the way it was delivered. The job was left to Multiculturalism Minister David Collenette, and his apology of sorts was hurried through in five paragraphs in the middle of a self-congratulatory 11-page blurb on federal efforts to foster multiculturalism.”12

Was this Liberal government offer, soundly thrashed by major newspapers, arranged by a few individuals from Toronto’s Japanese community in secret meetings with David Collenette? This was the question on the minds of many prominent Toronto NAJC members. Imai had lost his credibility in the Toronto JC community by then and he had been forced to resign as chairman of the National Redress Committee after a June 17, 1984 teleconference of the National Council of the NAJC. But, despite the loss of his role, he still tried to speak on behalf of all Japanese Canadians. Shortly after being ousted by Art Miki, Imai told a Toronto Star reporter that the national association [i.e., the NAJC] had been taken over by “young radicals” and that he was forming a new group to represent the Japanese Canadian senior citizens, the “survivors” who had lost their property and belongings.13

As noted in Chapter 6, the “deal” with the Liberal government was certainly news to the rest of the Japanese Canadian community. Many individuals in the NAJC speculated that some backroom manoeuvring had gone on between the “George Imai group” and Trudeau’s circle. Mr. Imai’s autocratic action served as a turning point—a last straw that prompted several prominent members of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee (Wes Fujiwara, Roger Obata, Matt Matsui, Stan Hiraki, Kunio Hidaka and Harry Yonekura) to resign from this committee in disgust on June 14 1984 and begin the formation of the Toronto Chapter 27, of the NAJC.14

The alleged secret negotiations between Collenette and George Imai, behind the backs of the NAJC, represented a sad and shameful way for Trudeau to make his exit from office. As Maryka Omatsu eloquently expresses it, “Trudeau’s renowned steel-trap mind had no doubt been clogged by the debris of dead small animals. Lamentably, I regard Trudeau as a magician who dazzled us for over a decade with his social justice rhetoric that in the end was largely smoke and mirrors.”15

For many Japanese Canadians, the policies and actions of the Trudeau Liberals on the issue of Redress were disappointing. Pierre Trudeau’s passionate commitment in the past to human rights and social justice created an expectation in our minds that he would understand the principles under discussion and have personal interest in the righting of the wrong—a wrong that had been devised and executed by the Liberals of McKenzie King. When Trudeau stood up in the House of Commons that day in April 1984 and compared the plight of living, breathing Japanese Canadians to that of the displaced Acadians of pre-Confederation years, these expectations of social justice were shattered. It was clear that Trudeau had missed the point entirely.

The twists and turns of those final few Trudeau months stirred up a lot of bitter and intense emotions in our community. The media tended to sensationalize the schism, oversimplifying it as an individual versus group compensation split. This overly publicized “split” in our community was very convenient for the Liberal government. The old divide and conquer principle was in full operation, taking the heat off of the government.

The situation was far more complex than it appeared to be in the newspaper articles. Looking back on that period now, one can see that each incident, each disappointment or frustration represented a valuable learning lesson—a valuable step in the journey towards justice. Ironically, Trudeau’s arrogant attitude towards the Redress cause, although a major hurdle, proved to be a powerful catalyst for change. The rapid chain of events that was triggered by those two speeches in the House of Commons in April 1984, soon led the Japanese Canadian community out of its state of political paralysis.

As the voices and numbers of the NAJC supporters grew over that one year, the “other side” appeared to be desperate to strike a quick deal with the Liberal government before a federal election could be called. This, in turn, prompted Redress activists in Toronto to take immediate action to put a stop to the deal. It was a whirlwind of activity. Everything happened very quickly in those months before Trudeau stepped down—the public meetings, the networking, the soul-searching debates in our community, the media attention and the political wrangling. Trudeau’s emphatic ’no” only served to strengthen the resolve of those who were trying to achieve the justice that had eluded our community for over 40 years.

Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau in the early 1980s. Mr. Trudeau’s arrogant refusal to consider our claims for Redress was another slap in the face from a Liberal government. The Japanese Canadian community had expected more from the father of the “just society”. (Photo courtesy National Archives of Canada)

A smiling Trudeau during the 1977 Japanese Canadian Centennial receiving a gift from the JC community of Toronto—before his views on Redress became known. Noticeable in the background are Bill Kobayashi and Sid Ikeda, long time president of the Japanese Cultural Centre in Toronto. (Photo courtesy Roy Ito)

Liberal MP David Collenette of Toronto was multiculturalism and citizenship minister during the latter part of Trudeau’s final term. It was alleged that he held negotiations with George Imai. (Photo: Harry Yonekura)

Equality Now!, Report of the Special Committee on Visible Minorities in Canadian Society, came out in March 1984. It provided the Japanese Canadian community with its most powerful ammunition against Trudeau’s flimsy arguments.

The NDP never wavered in its support of our Redress struggle during the 1980s, following in the footsteps of Andrew Brewin, Angus MacInnis and Grace MacInnis. Particularly outspoken in the House of Commons were MP Lynn McDonald of Broadview-Greenwood riding, and Ed Broadbent, leader of the federal NDP from 1975 until 1989. It was Lynn McDonald who tabled a bill calling for Redress negotiations with the Japanese Canadian community. Ed Broadbent was equally supportive of our cause from the beginning, continually challenging Trudeau on the Redress issue. He spoke with deep emotion after Mulroney's annoucement of the Settlement on September 22, 1988. (Photos courtesy Lynn McDonald and The New Democratic Party of Canada)

Notes

1 McDonald, Lynn, Hon. “Visible Minorities: Treatment of Japanese Canadians During World War II.” In Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Debates. 32nd Parliament, 2nd Session. Vol. III (23 March 1984 17 May 1984). Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1984, p.2623. Statement was made on 2 April.

2 Trudeau, Pierre, Rt. Hon. House of Commons. Debates., p. 2623. Statement was made on 2 April 1984.

3 Broadbent, Edward, Hon. “Injustices Done to Japanese Canadians.” House of Commons. Debates, Vol. III (1984), p. 2715. Statement was made on 4 April.

4 Trudeau, Pierre. Ibid, p. 2715. Statement was made on 4 April.

5 Canada. Special Committee on Participation of Visible Minorities in Canadian Society Report. Equality Now! Report of Special Committee on Visible Minorities in Canadian Society, Issue No. 4 [Ottawa]: House of Commons, March 1984, p.61

6 The Toronto Star, April 7, 1984.

7 “PM Cool to Compensating Interned Japanese”, The Globe and Mail, April 3, 1984.

8 The Globe and Mail, April 10, 1984.

9 The Globe and Mail, Editorial, April 11, 1984.

10 Imai, Shin. The Globe and Mail, April 16, 1984.

11 The Globe and Mail, Editorial, June 22, 1984.

12 “Scarcely Half an Apology”, The Toronto Star, June 22, 1984.

13 McAndrew, Brian. “Split Leaves Two Groups Claiming to Speak for Interned Japanese.” The Toronto Star, June 19, 1984.

14 See minutes of Toronto JCCA Redress Committee meeting, June 27, 1984. Wes Fujiwara introduced a motion, seconded by Harry Yonekura to reconfirm support of and membership in the National Association of Japanese Canadians in light of the formation of a new separatist Redress group led by George Imai.

15 Omatsu, Maryka. Bittersweet Passage (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1992), p. 168.