Chapter 10

The Power Shifts

By the Ad Hoc Committee, Japanese Canadian Redress: The Toronto Story

Based on the notes of Roy Ito and the Committee

By January 1985, the acrimonious rift in Toronto’s Japanese Canadian community was blatant. A half a year earlier at the June 27, 1984 JCCA Redress Committee meeting, Dr. Wes Fujiwara moved, Harry Yonekura seconded, that the Toronto Redress Committee reconfirm its support of, and its membership in the National Association of Japanese Canadians. A vote and further discussion on this proposal was promptly halted when George Imai made a motion to table Fujiwara’s motion. When Imai’s motion was carried, Wes Fujiwara, Stan Hiraki, Kunio Hidaka, Roger Obata, Matt Matsui and Harry Yonekura walked out in disgust. This dramatic exit marked 1the beginning of a major power shift within the JC Redress movement.1 Prior to this point, the majority of individuals on the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee had sincerely aimed at presenting a unified voice on Redress. But when it became apparent that a handful of executive members were secretly carrying out a separate campaign without consulting the rest of the committee, many hard-working committee members felt deeply betrayed. It was no longer possible to work together under such undemocratic conditions.

The two years following the split in the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee were full of controversy. Public meetings turned into loud shouting matches. Personal accusations flew in every direction. And, instead of exploring our Redress campaign as a human rights issue, many journalists preferred to focus on the sensationalistic internal conflicts.2 The mid-1980s were indeed trying times for our community.

The voices opposed to individual compensation continued to argue that individual compensation constituted greediness and that it would provoke “a backlash”. However, by the end of 1985 these voices were waning as the cries for justice could not be suppressed.

National Redress Survivors Group

The division in the JC community deepened considerably in early 1985 when Jack Oki issued a statement from the “Japanese Canadian National Redress Committee of Survivors”. Oki announced that “the NAJC does not represent the opinions of the majority of the community” and that the Survivors group “cannot support the process of negotiation underway….” He wrote that he and the new organization supported a position of “compensation in a group form, in a trust or foundation” and “a position of reason and honour…in keeping with the dignity which was and still is the style of the issei, the first generation immigrants, who suffered the most from these injustices.” Oki also stated, “Fully recognizing the grav[ity] of the injustices and the consequences thereof, we still believe it is not right to attach monetary values to human rights.”3 A few months later this new organization, under the name of “Japanese Canadian National Redress Association of Survivors" (JCNRAS), distributed an introductory pamphlet in which it noted that one of its main roles was to promote the resolution of the Redress issue “without undue expense and burden on today’s citizens of Canada and without anachronistic recriminations.”4 Reading between the lines, one could interpret this statement to mean without rocking the boat and making waves that would upset the government or the rest of Canadian society.

Shortly after Oki’s statement appeared in The Canada Times, certain Toronto JCCA members began receiving letters from the Toronto JCCA executive, expelling them for becoming members of the NAJC North York Chapter. The letter, signed by both Ritsuko Inouye and Jack Oki, stated, “Consequently, we hereby advise you that your membership in the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee has been terminated…We wish you well in your new endeavours and hope that the matter of Redress can be resolved quickly with honour and dignity.” Harry Yonekura, a long-time Toronto JCCA member “in good standing”, received one of these letters, explaining that his membership was being terminated because of his involvement with the North York Chapter of the NAJC.5

When Yuki Mizuyabu received the same letter, he sent Jack Oki one of his own, questioning Oki’s power to decide who should or should not represent the Wakayama Kenjinkai. Mizuyabu informed him that he expected Oki to withdraw the letter of expulsion. He also requested a copy of the minutes of the last Toronto JCCA Redress Committee meeting. Oki never responded. Stan Hiraki, another recipient of the termination letter, was stunned by it. He had been Toronto JCCA president, vice-president and treasurer at various times. In a letter of protest, Hiraki pointed out that there was nothing in the constitution that stated that an individual could not belong to two different organizations at the same time. He suggested that Oki was being hypocritical since he had associated h6imself publicly with the “National Redress Committee of Survivors”.6 According to Hiraki, Oki should have been the first to have his membership terminated.

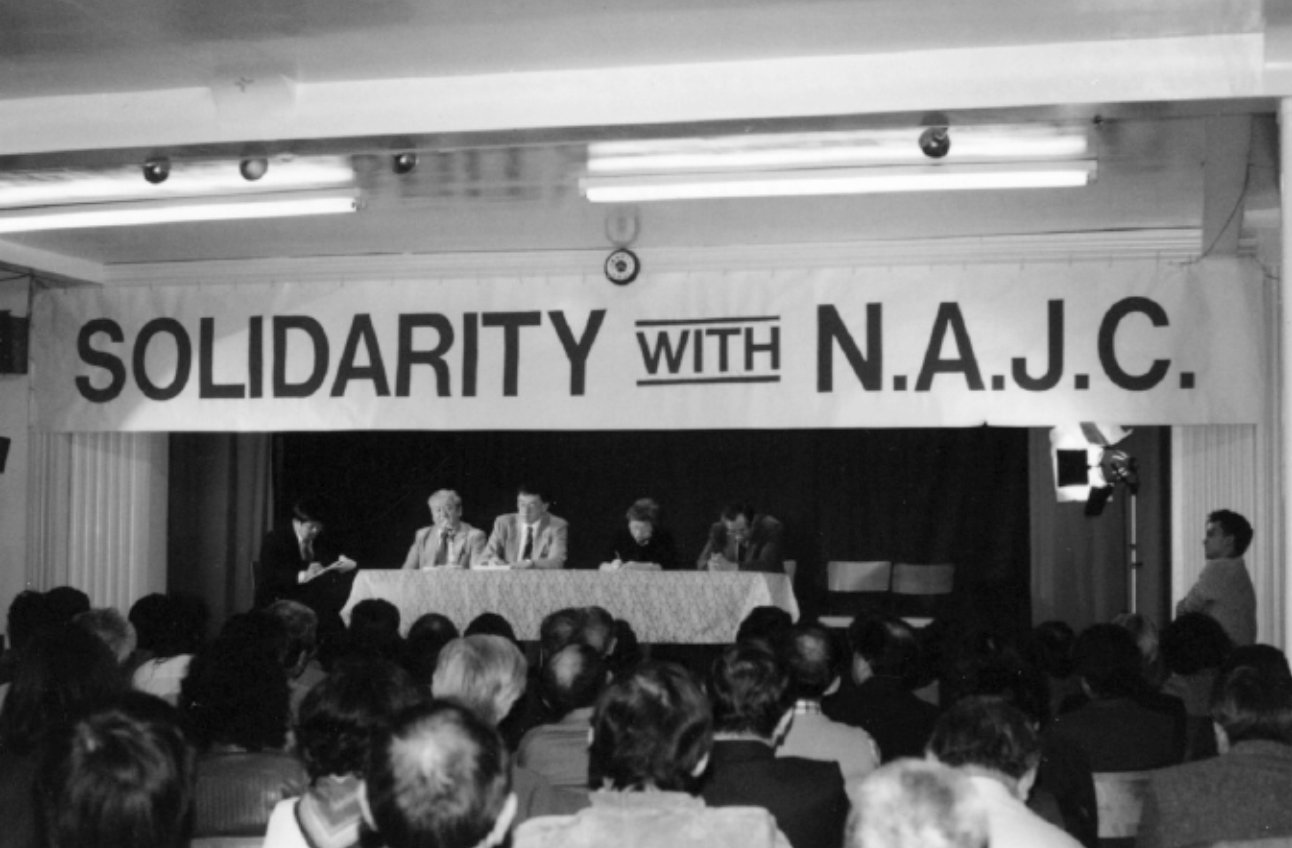

Miki Reports on the Six Million Dollars Insult

The ousted members of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee would not have to wait long to face Jack Oki in public. It was March 10, 1985. The community had gathered at a familiar location, the Japanese Centennial United Church at 701 Dovercourt Road in Toronto, for what was supposed to be a huge public meeting. Art Miki, our NAJC national president, was in town. He had come to Toronto to update our community on recent developments since presenting a brief to Mulroney in November 1984. The meeting, arranged by both the North York chapter of the NAJC and the Toronto JCCA, was intended as an opportunity for Japanese Canadians in Toronto to meet Miki and hear about the latest offer firsthand.

Miki had been in touch with Toronto JCCA president, Ritsuko Inouye, well in advance of his visit and he expected her to communicate the information to the entire Japanese community so that he could talk to as many Toronto area JCs as possible and get their input. However, none of the active members of the community received any kind of notification about Miki’s impending visit. We can only speculate about Inouye’s motives for keeping relatively quiet. When the NAJC’s North York Chapter found out about Miki’s visit only two days before his arrival, the members had to scramble to get the word out to the rest of the community.

As Yuki Mizuyabu remembers, “There we were in the basement of the United Church—a mere 150 people. It was embarrassing. Most of them, judging by their reactions to the proceedings, were already NAJC supporters who would have missed the meeting entirely if we hadn’t reached them through our telephone blitz."7 Only about a dozen were supporters of the “Survivors" organization.

The audience listened intently as Art Miki provided details about his frustrating negotiations with the federal government. In January 1985, Jack Murta, Mulroney’s first multiculturalism minister, suddenly announced that he was not actually “negotiating” with the NAJC, but merely “consulting” with them. This was now the case, despite the government’s December 1984 press release to the contrary. Murta’s representatives also informed Miki that the government would be introducing a “settlement” in parliament by the end of January—with or without the endorsement of the NAJC.

The proposed settlement package would include a pseudo-apology, that is, a mere acknowledgement that “a wrong was done”, plus $6 million to establish an educational foundation. This was just $1 million more than what the Liberals had been willing to consider. The funds and the decision making would be in the hands of a board of nine members, five of whom would be Japanese Canadians, but only during the first three years. At the end of the initial three years, there would be no assurance that any board members would be of Japanese ancestry. This arbitrary plan also stipulated that only the annuities generated from the principal would actually be available for spending, an amount estimated at only $600,000 per year.

Outraged voices could be heard throughout the room as Miki disclosed the government’s efforts to push their unilateral plan through the back door by contacting certain individuals in our community to secure their endorsement, while publicly saying that they never intended to impose the plan upon us without our consent. According to Miki, the majority of Japanese Canadians whom he had spoken to by that point rejected the proposal completely. How could we possibly accept a proposal that only allowed our community to use the annual earnings—and only guaranteed our participation on the foundation’s board for three years? The deal on the table was clearly an insult.

Following the disappointing update, things got even more heated up. Miki led a question and answer session and then asked the audience to indicate, by a show of hands, whether or not they agreed with his decision to oppose the $6 million offer. He also wanted to know how the audience felt about asking the government to accept the principle that the amount of compensation should be proportional to the damage suffered and that the affected individuals should be compensated, not only collectively, but also individually. The multitude of raised hands gave Art Miki the mandate to follow his own convictions. More than 90% of the audience was behind him. Only a small handful opposed his proposal.

Oki Resigns

During the proceedings, Jack Oki, the NAJC vice-president, had trouble staying seated. He kept getting up on the stage to make statements criticizing the NAJC Redress negotiations. He, in turn, was repeatedly heckled by members of the audience. Hide Shimizu, who was helping to maintain some semblance of order as the moderator, ran out of patience after seeing Oki approach the stage for what seemed to be the hundredth time. In exasperation, she asked him to stop monopolizing the stage. Tension mounted in the audience as Oki ignored her and continued to make anti-NAJC statements. Unable to contain herself, the late Hisa Mori, an issei and mother of NAJC member, Yo Mori, shattered the stereotypical image of the submissive, old Japanese woman by shouting repeatedly at Oki to get off the stage. Terry Watada later informed some members of the audience that Mrs. Mori was a woman “with a strong sense of justice…who would not go along with anything that was crooked”.8

Finally, Harry Yonekura stood up in the audience to thank Art Miki for his report. Yonekura then said, “Mr. President, if Jack Oki is the vice president of the NAJC, then I think you have a problem because…” Everyone in the room was painfully aware of the fact that Jack Oki was a problem since he was publicly opposing NAJC President Art Miki, instead of displaying a united front. Before Yonekura could finish his comments, Oki had managed to pop up on the stage again. But this time, he didn’t go up to raise another criticism. He stunned everyone by announcing his immediate resignation as vice-president of the National Council, NAJC.

Oki’s offer to resign was met with thunderous applause and enthusiastic cheers from the audience. According to Yuki Mizuyabu’s observations, “Oki looked a little startled by the sighs of relief and the expressions of unreserved elation in the room. If there were any moans from his supporters or pleas to stay on, they were drowned out by the loud cheering and clapping.”9

Jack Oki’s dramatic resignation proved to be one of the most pivotal moments in the journey towards justice. It was historically significant because it removed official spokesperson status from still another person whose position on Redress had been at odds with that of almost all the others in Toronto who were actively participating in the movement. With the departure of Oki and George Imai from their national executive positions, Ritsuko Inouye’s power and authority became diminished. She still held the title of Toronto JCCA president—even though she had not renewed her mandate to represent the chapter since the annual general meeting of 1980—but she was losing her credibility as a community leader as the new North York chapter of the NAJC was becoming recognized as the legitimate voice on Redress matters.

Despite the relatively low turnout for the United Church meeting, the event was momentous. Miki was very pleased with the results achieved. The power base within the Japanese Canadian community had definitely shifted. The majority of Toronto’s Japanese Canadians seemed to support the notion of keeping up the struggle for an equitable deal.

Although Oki continued to attack the NAJC in articles in The New Canadian and The Canada Times, his attempts to stop the Redress tide were futile. His arguments against individual monetary compensation were too flimsy. They were based not on any legal precedents, but on the fear of “a backlash” from the larger Canadian society—that oppressive, self-defeating fear of making waves and upsetting our Anglo-Canadian neighbours—the fear that kept us suffering in silence for 40 long years. Ironically, it was the desire to overcome this fear that spurred on many of the nisei and sansei actively involved in the Redress movement. The old backlash theory had been blown down.

City of Toronto Grant for Price Waterhouse Study

The bitterness separating the NAJC and the few executive members controlling the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee came to a head a few weeks after Oki’s resignation when the City of Toronto Council decided to grant $5,000 to fund the NAJC Price Waterhouse study on wartime losses incurred by Japanese Canadians.10 In April 1985, Mayor Art Eggleton received a letter signed by Jack Oki, as chairman of the Toronto Redress Committee. In it, Oki stated the following:

We understand that the City Council is considering a monetary grant to the National Association of Japanese Canadians.

As the organization representing the Japanese Canadian community in Toronto, we strongly object to such use of public funds.

Please find enclosed copies of letters, resolutions and a list of organizations that are represented on our committee.

We would appreciate an opportunity to personally explain our position and the dilemma facing the Japanese Canadian community as we need all Canadians of good will and reason to help in resolving this very divisive issue not only for the sake of Japanese Canadians but all Canadians.

Please consider this matter as one of primary concern to your constituents of Japanese ancestry.11

The NAJC quickly conducted a survey of the organizations that Oki claimed were behind the Toronto Redress Committee’s objection to the $5,000 grant. The survey showed that some organizations listed by Oki no longer existed, were inactive or unknown. Bill Kobayashi, corresponding secretary of the North York chapter, reported that none of the organizations mentioned officially supported Oki’s Redress position. None had approved of the letter to Mayor Eggleton.

Oki had shattered his own credibility through his letter to Eggleton. Others in the Toronto JC community could not comprehend his objection to the grant. As Bill Kobayashi put it, “I wish these people would explain why they object to a grant to research the losses our community suffered in the War, research which benefits the entire community.”12

Understandably, Oki’s letter would have been quite opposite to the reaction the municipal politicians might have anticipated to their offer of financial assistance to the Redress movement. To deal with the dilemma created by the letter, Eggleton invited Oki and other interested members of the JC community to meet with the Mayor’s Committee on Community and Race Relations (MCCR), in a committee room near his office, to discuss the community’s “position” regarding the proposed grant.

Jack Oki and George Imai declined the invitation, yet as representatives of the National Redress Committee of Survivors, they asked to meet privately with Art Eggleton before he and the MCCR met with other representatives of the Japanese Canadian community. Clearly, they wanted to avoid a larger forum that would involve opposing views from the JC community. Before the MCCR meeting, Oki, George Imai and four or five other individuals were seen going into Eggleton’s office after getting off the elevator at the mezzanine floor. After a few minutes, they came out, went down the elevator and quickly departed, not even bothering to take a peek into the committee room where the MCCR was preparing to meet with other JCs. Watching them, Mizuyabu notes that his first thought was, “if they were dogs, they would be fleeing with their tails between their hind legs.”13

Maryka Omatsu addressed the MCCR, speaking on behalf of the approximately 25 Japanese Canadians in attendance. In effect, she told the committee that the Japanese Canadian community is not unlike the greater Canadian society—that there are individuals, like Jack Oki, who misrepresent themselves as spokespersons of the community. She urged the MCCR to reaffirm the city’s grant to the NAJC. After her brief speech, the committee promptly endorsed the grant, convinced that the majority of local Japanese Canadians, contrary to Jack Oki’s letter, welcomed the financial assistance offered by the City of Toronto to help finance the Price Waterhouse study. Alderman Michael Walker formally presented the $5,000 cheque, along with the municipal government’s best wishes, to President Art Miki on November 10, 1985.

Despite this low point for the National Association of Survivors, its members continued their campaign with dogged determination. They lobbied many politicians in Ottawa, but to no avail.

Cambridge Hotel, November 1985

The next decisive meeting in our continuing struggle for legitimate representation of the Toronto JC community took place at what was then the Cambridge Motor Hotel in suburban west end Toronto. For three days, November 9-11, 1985, it was the site of one of the most memorable meetings of the NAJC National Council.

The National Council passed a motion to continue to recognize the North York Chapter of the NAJC as the official representative of the Toronto Japanese Canadians in matters pertaining to Redress. The national body removed the Toronto JCCA from this position by taking away its five votes and giving them to the North York Chapter. This controversial motion was carried with 16 “yes” votes, 8 “nordquo; votes and 4 abstentions.

At this point, the organization that was to become the future “NAJC Toronto Chapter” was still forced to use the name “NAJC North York Chapter”. North York was where the chapter’s president, Dr. Wesley Fujiwara, lived and in the days before municipal amalgamation, it had a large enough population to warrant a separate chapter. As noted earlier in this book, the NAJC could not recognize two representative organizations from one geographical centre.

The motion to recognize the North York Chapter was prompted by the fact that the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee had passed a resolution withdrawing its support of the NAJC’s actions on Redress. The cutting of organizational ties was helped along further when the Toronto JCCA president failed to cooperate when asked to share a list of enames and addresses for the mailing of the NAJC newsletter.14

Despite the numerous items on the Cambridge Hotel meeting agenda, the council allowed Frank Hayashi of the Toronto Issei-bu to read a prepared statement, a statement that sounded conciliatory and suggested that past differences should be forgotten so everyone could work together for the benefit of the community. After the meeting, in a gesture of reconciliation, Wes Fujiwara asked Yuki Mizuyabu to contact Mr. Hayashi to request a meeting with him. When he called him the next day, his immediate response was “atte mo iina” (or “I suppose we should meet.”) Mizuyabu left it up to Mr. Hayashi to decide when and where, but about three weeks elapsed with no word from him.

Wes advised Yuki to try again. Apparently, Mr. Hayashi was no longer interested in working with anyone from the NAJC on the Redress issue. When pressed for the reason for his sudden change of attitude, he kept repeating nervously, “kekku a-u-to sare ta, kekku a-u-to sareta” (or “we’ve been kicked out, kicked out”). Like many other issei associated with the old guard of the Toronto JCCA, Mr. Hayashi could not see the fact that he had unwittingly made the choice to dissociate himself from the national organization. No one “kicked out” the Isseibu. In fact, Frank Hayashi was the one who introduced the motion stating that the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee could no longer support the NAJC Redress initiatives. And instead of starting off his motion with “we, the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee…”, he said “we, the Issei-bu…”

The official recognition of the North York Chapter made the Cambridge Hotel conference of November 9-11 one of the milestones of the Redress campaign. As expected, it was followed by numerous articles in The Canada Times and The New Canadian condemning the decisions made against the Toronto JCCA. For example, George Imai referred to the November 9-11, 1985 event as a “banquet of shame” designed to “celebrate the ejection of the Toronto JCCA”. Imai also called the NAJC members “radical newcomers”. He wrote: “It is a shame that the traditional respect and honour of the Japanese Canadian culture and heritage have not been taught to these raw new radicals. This disreputable event shows the weakness and the desperation of the radicals.”15

Then in January 1986 came the telegram from Ritsuko Inouye to Art Miki notifying him that the executive of the Toronto JCCA had passed a motion to sever the connection between the Toronto JCCA and the NAJC. The division was complete and official. The parent organization no longer had any jurisdiction over their former Toronto chapter. Now there were two distinct organizations in Toronto claiming to be the voice of Redress. Those few individuals who portrayed themselves as the spokespersons for the “majority” of Japanese Canadians in Toronto were out there alone without the support of a larger, nation-wide organization.

Apparently, Inouye and the other JCCA executives did not believe it was necessary to consult the general membership of the Toronto JCCA. Perhaps they believed that they knew what was best for both the JCCA membership and the Toronto JC community. None of the JC newspapers carried any articles of any meetings of the Toronto JCCA to decide on seceding from the NAJC. In fact, the JC community newspapers encouraged this undemocratic behaviour by only reporting the executive’s announcement. None questioned their authority to take the action. Perhaps the majority of the community remained silent because they had by now abandoned any thought of having Inouye, Imai or Oki represent their interests. In addition, the Toronto JC community now had a democratically organized rival group, recognized by the NAJC, to represent the community on Redress.

Formation of Toronto Ad Hoc Committee for Japanese Canadian Redress

Following a proposal by Roy Miki of Vancouver, Joy Kogawa was instrumental in getting the National Coalition organized, an off-shoot from the congregation of the Church of the Holy Trinity. Several public meetings were held at Holy Trinity. Milton Harris of the Canadian Jewish Congress gave a stirring speech on Redress which received positive media coverage. Following one of the meetings, Cyril Powles, a retired Anglican minister, and Frank Cunningham, a U of T professor, contacted Harris to see if they could do something concrete for Japanese Canadian Redress. Soon the Toronto Ad Hoc Committee for Japanese Canadian Redress was formed. Its original members were: Gregory Baum, Ernie Best and Helen Best (former teachers at the Tashme camp), Frank Cunningham, Lee Creal, Michael Creal, Ben Fiber, Alice Heap, Dan Heap, Michael Lyons, Bruce McLeod, Cyril Powles, Marjorie Powles and Wally Majesky. Ben Fiber and Joy Kogawa were also key people in the background whose support and community contacts were of enormous value.

This new committee was comprised of individuals who had supported the Redress movement in the early 1980s, as well as former members of the Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians (CCJC) whose association with the JC community went back 40 years. Led by Cyril Powles, the Ad Hoc Committee began mobilizing the support of hundreds of ordinary Canadians.

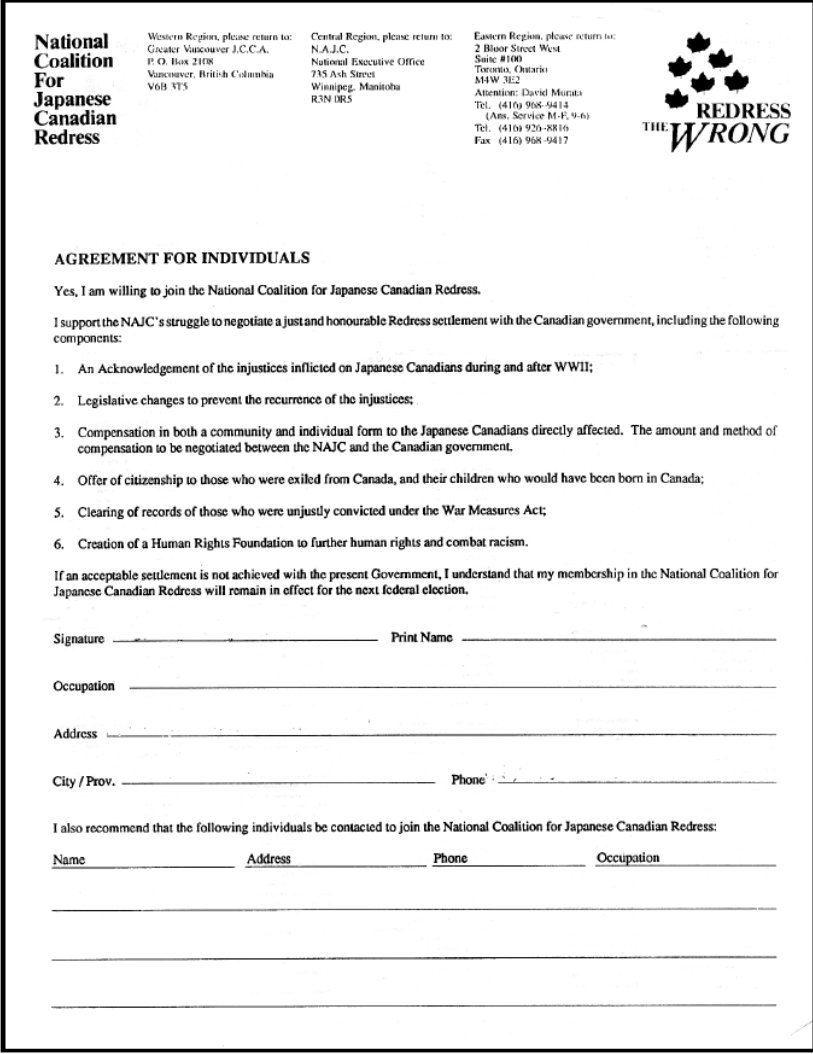

The Ad Hoc Committee began its campaign with an appeal for funds in The Globe and Mail, March 6, 1986. The advertisement, designed by a professional advertising company, showed children in an internment camp with the caption, “In 1942 Canada sent a lot of kids to camp.” There was also an eye-catching logo containing the Canadian flag and the words, “RIGHT THE WRONG”. After the ad appeared, hundreds of donations arrived, ranging from $10 to $100. The advertisement cost approximately $25,000. The balance left over from the donations, around $5,500, was turned over to the NAJC.

Through the Canadian Council of Churches, a formal petition was sent to Ottawa. The petition contained 1,500 signatures supporting financial compensation, a formal apology and changes to the War Measures Act. Cyril Powles reported that the Ad Hoc Committee on Japanese Canadian Redress received some poison pen letters and nasty telephone calls as well. A few war veterans phoned and severely criticized him for supporting Japanese Canadian Redress. However, a national poll, paid for by the Ad Hoc Committee, indicated that 63% of Canadians were in favour of some type of Redress and 71% favoured individual settlements.16

As time went on, the supporters of the Redress campaign began to sense that opinion was changing, that people who had been sitting on the fence had moved off the fence. The support of other Canadians gave the JC community the boost it needed. Many Japanese Canadians who had previously expressed the fear of a backlash were feeling more comfortable now about the direction of the Redress movement.

With the support of other Canadians and the growing legitimacy of the North York chapter of the NAJC, the Redress campaign could move full steam ahead. The small group of individuals who still wanted to settle the Redress issue without community input was officially stripped of its power to speak on behalf of the Toronto Japanese Canadians on the issue of Redress. Therefore, when the Survivors Group lobbied Ottawa MPs on June 4, 1986, they did not come across as very credible. Both the NDP and the Liberal parties reaffirmed their support for the NAJC, issuing statements recognizing the NAJC as the only legitimate organization representing the Japanese Canadian community.

Ernie Epp, NDP MP for Thunderbay-Nipigon, wrote a disapproving letter to Jack Oki, dated June 6, 1985. It stated:

It remains vital for Japanese Canadians not to weaken the hand of their national leadership in achieving the best possible Redress agreement. An open struggle between the two groups for the support of Japanese Canadians and over the terms of Redress can only have a negative effect on the entire process.

I am told that the activity of your group arose from Mr. George Imai’s attempt in 1983-84 to arrive at a Redress package without the authorization of the NAJC in whose name he was ostensibly acting. This is a serious charge and, if it is true, provided no justification for becoming active in the Redress process in any independent way.

Having considered these matters carefully yesterday, the New Democratic caucus reaffirmed its support for the negotiation process that the National Association of Japanese Canadians is pursuing with the government…"17

Unparliamentary Procedures at Toronto JCCA’s AGM, July 1986

Ever since the Sodan Kai-sponsored public meetings of 1983, the issue of Toronto JC representation became a major concern for many individuals. Those interested in exploring this question joined the Ad Hoc Committee of Concerned JCCA Members, a committee formed in February 1986 to try to bring democracy back to the Toronto JCCA.18

It was soon discovered that the Toronto JCCA had been dormant since its 1980 Annual General Meeting. President, Ritsuko Inouye, had brushed aside requests for a meeting with her in 1985 with a telegram stating, “your concerns will be dealt with in due time”. A delegation was finally able to meet with Inouye on April 23, 1986 in the presence of her supporters and other interested parties, including representatives from the new Ad Hoc Committee of Concerned JCCA Members, the Japanese Canadian Association of Survivors, the Greater Toronto Chapter of the NAJC (formerly North York Chapter) and the Coalition of Concerned Japanese Canadians (a short-lived organization led by Kinzie Tanaka and Edward Ide which advocated national consensus on Redress through support of the Toronto JCCA).

The participants at the meeting included: Charlotte Chiba, Wesley Fujiwara, Frank Hayashi, Edward Ide, Henry Ide, Ritsuko Inouye, John Kawaguchi, Sam Nishiyama, Roger Obata, Jack Oki, Koichi Okihiro, Mits Sumiya, Issaku Uchida and Harry Yonekura. In reference to the current community schism, Kadota and Shimizu expressed their concerns that the fallout would affect the well-being of the community far into the future. They also touched on the prickly question of group versus individual compensation. It was announced that a questionnaire was being sent out by the NAJC which should provide an answer one way or the other on the Redress question. The Ad Hoc Committee congratulated the opposing forces for agreeing to come together face to face, noting that such a meeting was in itself a positive step.

This meeting with Ritsuko Inouye was significant because she made a commitment to hold a long overdue annual general meeting of the Toronto JCCA. She admitted that the Toronto JCCA had not held an annual general meeting for several years, but she said it was because of lack of community support. In any case, the date was set for May 25. But somehow an entire month passed without any further mention of a general meeting or even an explanation about its cancellation. After the ad hoc committee had almost given up hope, Inouye surprised everyone by announcing that an annual meeting would take place on July 5, 1986 at the Centennial United Church on Dovercourt Road. George Kadota, chairman of the Ad Hoc Committee of Concerned JCCA Members, was not informed of this meeting until June 24, by a letter post-marked June 23, giving him far less time than the usual 30 days notice required to communicate with the other members.

Kadota, fearing that the Toronto JCCA executives might try to evade certain issues, prepared a list of questions and sent them to the “elections chairman”. Among other questions, he asked if the National JCCA constitution would apply if the chapter did not have its own constitution. In addition, he asked what the term of office of the Board of Directors was, when and where the last general meeting was held, the legality of proxy voting in the election of officers—and how anyone could be expected to submit nominations in writing by June 27—to an unknown and unnamed nominating committee, when the members had not yet or had just received the notice. Kadota’s letter also advised the elections chairman to stick to moral and democratic procedures and plain common sense.

Past experience with the JCCA executive had helped sow strong doubts in the minds of many Toronto Japanese Canadians about the level of democracy at this July 5 meeting. Traditionally, at past annual general meetings, one of the first things one encountered upon arrival was a desk where one could pay the membership dues for the new year. There was no one sitting by the door waiting to register old or new members. Instead there was a desk with different coloured cards on it. Those who had somehow paid their dues in advance for the New Year were handed a card that represented one or more votes, depending on its colour.

A few people, mainly elderly issei, had come well prepared for the meeting. Apparently, they had already paid their dues and had even been given proxy votes from members who could not attend. They received cards representing two or more votes. Later it was learned that each of the executive members also had proxy votes. Many individuals who were physically present at the July 5, 1986 meeting were shut out of the voting process because they had not paid their membership dues yet. But when they expressed the desire to pay, they were told “we’re not accepting membership dues today. If you haven’t already paid, you do not have a vote.” In the past, the Toronto JCCA used to request the payment of membership dues by mail. The members would then remit their dues by mail or pay it at the door if they attended the annual general meeting. But, for this 1986 annual general meeting, none of the JCCA members who belonged to the ad hoc committee received any form of request to pay JCCA membership renewals. Yuki Mizuyabu got the distinct feeling that the executive only wanted certain members in their organization—only those who would go along obediently with the Redress strategy of the Toronto JCCA executive. Some of the members had avoided the situation of an expired membership by taking out lifetime memberships or paying in advance at an earlier Issei-bu meeting.

Aside from the fact that most of the people present were denied the right to pay their membership dues, there were several other bizarre aspects of that July 5 annual meeting. No one passed out minutes of the previous annual general meeting, a meeting that occurred six years before the current one. Thus, there was no tangible proof of anything that transpired at the annual general meeting in 1980. Also missing were any attempts to ratify the more serious actions taken by the executives. The general membership was not asked to ratify the establishment of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee and the Toronto JCCA’s unilateral severing of ties with the NAJC. In the view of many of those present, the entire annual meeting was a travesty, a joke. There was no attempt to follow accepted procedures for conducting an orderly, democratic meeting.

In her “President’s Message”, Ritsuko Inouye announced that she would only serve one more year as president. She stated that she had actively served the Japanese Canadian community for over 40 years, the last ten as president of the Toronto JCCA. She felt she had worked diligently in ensuring that her executive committee kept the Toronto JCCA operating when there was a waning of interest in the organization.

Inouye’s message was followed by the “election” to select a new board of directors. According to many observers, this election was an insult to all those who bothered to show up. As Yuki Mizuyabu saw it, President Inouye arbitrarily rejected any nominations from the floor. Asked if she was empowered to do so by the constitution, he heard her reply, “We have no constitution.” Bill Kobayashi, another observer at the meeting, echoes Mizuyabu’s observations. He recalls that moments before the voting, Rits Inouye declared, “Since we do not have a constitution, we can do anything we want.”

So, with no nominations accepted from the floor and with many of the participants denied a vote for not having paid their membership dues (even though they were willing to pay), Inouye called for a vote to approve a slate of nominees for the new board. Needless to say, the executive prepared this proposed slate. The New Canadian reported that several members of the audience loudly challenged the legality of the voting procedure. One neutral observer remarked: “One had to be there ur to believe it.”19 Before the actual vote took place, the chair was, for reasons not explained, taken over by George Imai. He quickly called for a vote to approve the 20 names on a printed list—a list that included members of the previous executive, the chairs conducting the election as well as those individuals acting as the scrutineers to count the votes represented by the coloured voting cards.

Yuki Mizuyabu’s daughter, Lilian, could no longer tolerate the corrupt practices she was witnessing, the total disregard for rules of order. Yuki Mizuyabu recalls his daughter’s actions vividly:

Impulsively, [Lilian] stood up and grabbed some voting cards that were left unattended on a table and attempted to distribute them to the unfairly disenfranchised participants. I remember seeing Jack Oki following her frantically. Lilian was holding a three year-old relative by the hand at the time. She tried to fend off Oki with the other arm, but was in danger of being knocked down. Her cousin, a fairly tall young man, witnessed the incident and stepped in between. He told Oki, “You touch her, and I’ll deck you.” Oki had to back off. Recalling the event several years later, my daughter could not remember if she succeeded in distributing any of the mcards. I think she did.20

Before the vote could take place, a member from the floor pointed out that a list of nominees that he had submitted two weeks before had not been presented to the members for consideration. Yuki Mizuyabu remembers George Imai’s response: “He said that it was decided at the executive meeting of July l2, 1986 that any member who is also a member of a rival association [i.e. the NAJC] is automatically disqualified from holding office in the Toronto JCCA.”21 Somehow this new stipulation disallowing dual membership did not seem to apply to the Toronto JCCA executive members who were members of the National Redress Committee of Survivors—or the Japanese Canadian National Redress Association of Survivors.

Everyone was talking at once. The room was in an uproar. George Imai appeared to ignore the many calls coming from the members to follow proper democratic procedures. He called for a vote and the slate of 20 was elected by what he stated was a majority of 67 to 30. However, according to the recollections of many others at that meeting, there were at least three times as many “nays” as the chairman claimed. By the time Harry Taba reported them in The Canada Times, the number had been arbitrarily inflated to more than 200 to 30. Yuki Mizuyabu recalls that he had submitted an article for the Japanese section of the newspaper and when it appeared, he was shocked to find that the “for” vote count in his article had been increased by 200! Mr.Taba, the editor, refused Mizuyabu’s formal request to print a correction of this gross error. Instead, Harry Taba wrote his own Japanese article in which he said that the JCCA executive had 200 more proxy votes in reserve and that they would have been used if necessary to defeat the opposition. Referring to this reserve of 200 proxy votes, Mizuyabu notes, “the Toronto JCCA election was like a crooked card game in which certain players held hidden cards up their sleeves.”22

In another voting irregularity, Yuki Mizuyabu looked over to where several issei women sat together in a compact group. He recalls seeing “Tomi Iwashita, a post-war immigrant, standing before the group, trying to persuade the women to vote for the existing executive slate.” He walked over to her and asked her to stop it. In defending herself she said that she disliked “tairitsu” (i.e. conflict). Mizuyabu told her, “There’ll be more conflict if you don’t stop counselling the women on how to vote.”23

Those on the slate and elected were: Shizuko Eguchi, Frank Hayashi, Edward Ide, Henry Ide, George Imai, Ritsuko Inouye, Ken Kusaka, Reginald Mori, Denise Nishimura, Beverley Oda, Ross Ogaki, Jack Oki, Koichiro Okihiro, Yoichi Saegusa, Janet Sakamoto, Fumi Sasaki, Masakazu Shimoda, Mits Sumiya, George Takahashi and Sumie Watanabe.

When the election was finally over, the executive members hurriedly departed. It appeared that their only purpose that day was to retain control of the Toronto JCCA and they certainly succeeded. As they were leaving, Yuki Mizuyabu went up to the stage. Taking the microphone from George Imai, he suggested to those remaining that they “now have a democratic meeting of the Toronto JCCA.” Over 100 people remained for the meeting chaired by sansei lawyer, Marcia Matsui. Emmy Nakai, who did not live to see the Redress settlement, was designated secretary to record the second meeting. Mizuyabu was asked to translate the proceedings as necessary.

Several motions were passed. Tatsu Sanmiya moved, seconded by Doug Arai, that, in view of the flagrant dereliction of duties and responsibilities, the caretaker executive no longer be recognized as such and that the Toronto JCCA chapter form a new executive. Another motion, moved by Dick Takimoto and seconded by Bob Takagi, was passed stating that, as a direction to the Ad Hoc Committee, the election conducted by the Toronto JCCA [that took place at the AGM meeting that day] is under protest by the people present for the following reasons: 1) proceedings of election were undemocratic, 2) proxies unclear, 3) rules of the election were not made available in advance of the meeting, 4) scrutineers were not duly appointed, 5) no nominations from the floor were allowed.

A further motion, moved by Joy Kogawa and seconded by Roger Obata, empowered the Ad Hoc Committee to hold, if possible and practical, a proper general meeting and a democratic election to replace the illegal proceedings opposed by the people at the meeting. The last motion, moved by Wes Fujiwara and seconded by Mary Adachi, called for the Ad Hoc Committee to notify David Crombie, Lily Monroe and the ethnic press about the results of this meeting and the fact that the newly elected executive were not truly representative of our community.

Emotions were running high after the chaos of the July 5, 1986 meeting. On July 25, 1986, a troubled Joy Kogawa had a long telephone conversation with Takeo Arakawa in Vancouver, a man listed by the Japanese Canadian National Redress Association of Survivors as one of its honorary chairmen.24 Arakawa vehemently corrected the impression that many issei supported the Survivors Group. Joy recalls his words:

“We are—you can call us a group—maybe. We do not have elected members…We just have our opinion. And we do not speak—never—against NAJC. We never speak against anyone. We are old people, getting older. The only asset we can leave for the future is our name. I do not listen to any side. We need compromise. I don’t see compromise…From the beginning of the Redress movement, I said unity of Japanese Canadians is the most important matter to consider…. We must not allow ourselves to become a separated community—separated from each other and separated from the rest of Canada.”

Kogawa told Mr. Arakawa she hoped that it was not too late. And although many nisei in the past had the psychological need to reject the issei because of the serverity of anti-Japanese prejudice, she believed that Japanese Canadians were entering a new era in Japanese Canadian history. She claimed that the movement for Redress was rebuilding the community, and that a time of healing among the generations was at hand. “That,” Mr. Arakawa said, “would be the happiest thing. So dattara ichiban ureshi!” he said.25

Seven Points of the Survivors Group

Three months later the Survivors Group was still determined to popularize their position. They used The New Canadian as a vehicle to present their case to the community. The following seven arguments appeared in an article on October 3, 1985. Because of its length, only the relevant sections of it are included as follows:

-

We have no legal basis for seeking Redress.

What the government did to the Japanese Canadians in 1942 was despicable but it was legally done. The government had the proper legislation and the proper authority to pass the orders-in-council, etc., and it did everything legally. If we were to take legal action the chances of success is five per cent or less. It would cost two or three million dollars and it will take five years to get a judgement….it is a grave mistake on our part to pursue monetary compensation, individual or otherwise. -

We have moral grounds for seeking Redress.

Political leaders and the majority of Canadians agree that the action of the government was mostly wrong and therefore the political leaders are willing to acknowledge the wrong done to us. We believe the most important thing in Redress is to ensure that similar wrongdoing will not happen again…We believe that other matters are secondary. -

We do not hesitate to ask for funds.

We will use the income from the funds to help the older survivors who are finding it difficult to make a living or survive; to assist in our Old Age Homes, extended nursing care facilities, cultural centres, for a limited number of years. The government should reinstate the citizenship of those who lost their citizenship. We believe that the fund should be at least $25 million. -

Redress cannot be achieved by confrontation.

The only way to achieve (Redress) is not by confrontation. There are ways and means of achieving this. It requires knowledge, skill and acquaintances and a host of other elements. We must be also aware of the pitfalls that you may fall into. It is our opinion that the present NAJC leaders have failed to do so. We do not believe the present leaders have personal acquaintances among the present political leaders nor have personal contact with all the political personalities who count in achieving some success. We know as a fact that our group has much more contact with all the political leaders. We believe that the present NAJC leaders are politically naïve. -

We are not the George Imai group.

It has been said that our group is George Imai’s group. May we emphatically state that it is not so. Our group consists of many past executive members of the National JCCA, members who dedicated, toiled many long hours, days, years to carry on the work required of a national, provincial and local branches of the JCCA when they were not appreciated, for no remuneration whatsoever. George Imai is one of them and only one of them. Most of the prominent issei, well known among the Japanese Canadians, many prominent nisei and sansei, are supporters of the Survivors. Many of us belong to Japanese Canadian organizations and churches and we have personal contacts with many of the survivors. We believe…that we represent the majority view of the Japanese Canadians who are survivors and who are the only persons who are entitled to Redress legally…We have endeavoured to present our moderate views regarding Redress and we have presented them democratically and we have functioned democratically. However, much to our dismay the present leaders of the NAJC used all techniques and ousted us. -

The NAJC leaders are not presenting opposing views and truthful facts.

We admit that the present NAJC leaders are young, well educated, articulate, well organized and well versed with the techniques to present their views skilfully without arousing the curiosity of the readers as to the opposing views and truthful facts. We also admit that the leaders of the Survivors are old, suffering from poor health…lacking in communication skills, and do not have the funds; however, we all believe that we speak from our heart and we speak the truth. -

We should be magnanimous in victory and graceful in defeat.

We believe we have, in a sense, won this war or battle, since the government has publicly stated that they will apologize. Demand and payment for individual compensation, or setting up of endowment are not necessarily a success or a win. We believe we should be magnanimous in victory and graceful in defeat. You need not stab a person and then keep twisting the blade into him.

(The New Canadian, October 3, 1986)

Recognizing the True Voice of Redress

In the days following the stormy annual general meeting, Roger Obata, Stan Hiraki, Bill Kobayashi and many others wrote letters to the editor, in both the mainstream newspapers and the local Japanese Canadian community papers, condemning the undemocratic manner in which the annual general meeting and the election of a new executive were held. Many others wrote similar letters to both the federal and provincial ministers of multiculturalism. They requested that the two governments no longer recognize the Toronto JCCA as the representative body of the Toronto JC community until a proper general meeting could be held to replace the fraudulently elected executive with a democratically elected executive. A delegation from the second meeting of July 5, 1986 was dispatched to make these requests in person to officials in the provincial multiculturalism ministry. The responses at both levels of government were relatively sympathetic compared with the responses of previous politicians.

The JCs whom George Imai labelled as “radicals” were now the only ones who had the authority to negotiate a settlement. Those individuals representing the National Redress Committee of Survivors (or the Japanese Canadian National Redress Association of Survivors) had lost their credibility. The internal struggle within the JC community was finally fading and the Toronto NAJC members could now move on and focus all their time and energy on the larger struggle with the federal government.

By the fall of 1987, our struggle with the Government of Canada was given a tremendous boost by the formation of the National Coalition for Japanese Canadian Redress. The list of individuals and organizations publicly supporting our cause was a stunning testimony to the fact that our Redress struggle was not something confined to our tiny community. Public opinion was definitely on our side as more and more Canadians grew to view our case as a human rights issue involving the entire country. The names of supporters who joined the Coalition consisted of a broad cross-section of individuals, ethnic organizations, unions, professional associations and cultural groups. Among the first individuals to join were former Justice of the B.C. Supreme Court Thomas Berger and writers Margaret Atwood, June Callwood and Pierre Berton. It should be noted here that back in the 1940s, when many Canadian journalists were supporting the government’s racist actions, Pierre Berton was one of our trusted friends, writing honestly and sympathetically about the Japanese Canadians in periodicals such as Maclean’s. His name, along with numerous others, carried a lot of weight and swayed thousands of ordinary Canadians to join our cause. Faced with this overwhelming support for the NAJC’s goals, those opposed to individual compensation had no choice but to fade out of the spotlight completely.

We will never know what the underlying motives of the group compensation advocates were. Perhaps their arbitrary actions and disregard for democratic procedures were motivated by a genuine desire to serve the best interests of a community that, in their opinion, did not know what was best for it. Judging from the Canadian government’s past treatment of our politically insignificant JC population, perhaps they believed that getting a few million dollars for the community was the most they could hope for. It would be unfair to make any assumptions about what was going on in their heads at the time.

Those who advocated compensation to individuals believed in the principle that compensation should go directly to the injured party—to every Japanese Canadian whose rights were violated by the government’s racist actions. Their position was supported by an ever-growing number of people as more and more people became informed about what was at stake. Whether they would succeed or not was not as important as fighting for what they believed was right and following a democratic process to seek justice. Fortunately, the tide turned in the favour of the individual compensation advocates after the American government granted the Japanese Americans individual Redress.

It is interesting to note that only a few individuals, for personal reasons, have not applied for individual compensation. In fact, some of the advocates of token community compensation were among the first to apply for their Redress payment. Sadly, however, the conflict in the community appears to have left some deep scars, such as broken or strained friendships and family relationships—and feelings of guilt in those who accused NAJC supporters of being greedy and then turned around and applied for compensation themselves.

The final outcome of the Redress struggle might have caused some observers to regard one side of the community as winners and the other side as losers. But it should not be viewed in such a simplistic way. The final Japanese Canadian Redress Agreement was a victory for the entire Japanese Canadian community—and for all Canadians.

The Centennial United Church at 701 Dovercourt Rd. in Toronto was the site of many heated public meetings on Redress. (Photo: Blanche Hyodo)

Jack Oki speaking at the March 10, 1985, public meeting at Centennial United Church. (Photo courtesy Stan Hiraki)

Front cover of pamphlet of the JCNRAS, distributed in spring of 1985. Listed as executive members were Jack Oki and George Imai.

Public Redress meeting held at Centennial United Church, March 10, 1985. Left to right, Art Miki, Jack Oki, Elmer Hara, Rits Inouye and Wes Fujiwara. (Photo: Stan Hiraki)

RITSUKO INOUYE served the JC community in Toronto for many years as president of the Toronto JCCA. In her President’s Message at the July 5, 1986 AGM, she announced that she would only serve one more year a president. She also stated that she had worked diligently in ensuring that her executive committee kept the Toronto JCCA operating when there was waning interest in the organization. (Photo courtesy Stan Hiraki)

REV. CYRIL POWLES was born in Japan in 1918 to missionary parents posted in Niigata. He returned to Canada just before the outbreak of war in the Pacific. During World War II, Rev. Powles worked for the Anglican Church in their educational program for the Japanese Canadian children in the detention camps. He was a professor of East Asian Studies at U of T, and an organizer of the Toronto Ad Hoc Committee for Japanese Canadian Redress, a group that made a significant contribution for raising public awareness of Redress. He chaired the Ethnocultural Rally at Harbord Collegiate on October 29, 1987. (Photo: Harry Yonekura)

The Church of the Holy Trinity, a community oriented Anglican Church in downtown Toronto, was the site of a major protest rally to block a proposed $5 million deal negotiated by George Imai in June 1984. Japanese Canadians and their supporters met again at the Church of the Holy Trinity in 1986 for several public meetings on Redress. These meetings later led to the formation of the National Coalition. (Photo: Momoye Sugiman)

This form, inviting ordinary Canadians to voice their support of our Redress cause, was widely distributed and the response was overwhelming. See Appendix 2 for a list of the National Coalition Members.

Notes

1 See Chapter 6 for further details of the famous departure of Wes Fujiwara, Stan Hiraki, Kunio Hidaka, Roger Obata, Matt Matsui and Harry Yonekura from the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee.

2 The Canada Times was one paper that seemed to present only one side of the story, i.e. inflammatory, often libellous articles by the proponents of the group compensation package only. Often writing under pseudonyms, these individuals seemed to use the newspaper as a shield instead of participating in public meetings to defend their positions before the community at large.

3 Oki, Jack. “Statement from The National Redress Committee of Survivors", Canada Times, January 15, 1985.

4 Pamphlet of Japanese Canadian National Redress Association of Survivors, spring 1985. The names of the executive listed on the back of the pamphlet included: W. Hatanaka, E. Henmi, A. Namba, S. Sasaki, K. Morita, G. Yada, Y. Fukui, K. Tanaka, T. Nishimura, T. Arakawa, Y. Iwasaki, I. Uchida, H. Ide, M. Sumiya, G. Imai and T.J. Oki.

5 Oki, Jack. “Statement from The National Redress Committee of Survivors”. Canada Times, January 15, 1985.

6 It is unclear what the full official name of “Survivors" group was. In some newspaper articles it is referred to as “The National Redress Committee of Survivors” and in other places (such as their organization’s pamphlet) it is labelled “Japanese Canadian National Redress Association of Survivors”. Since the membership of both organizations appears to be identical, we are assuming that the two names refer to the same organization.

7 Mizuyabu, Yukihara. [Personal Journal.] 10 March 1985.

8 Mizuyabu, Yukihara. [Personal Journal.] 10 March 1985.

9 Mizuyabu, Yukihara. [Personal Journal.] 10 March 1985.

10 The Price Waterhouse study concluded the losses in 1986 dollars to be: income loss $333 million and property loss $110 million. George Kadota and Tsutomu Shimizu led a massive telephone fundraising drive that raised $10,000 towards the Price Waterhouse Study.

11 Jack Oki to Mayor Art Eggleton, Toronto, 18 April 1985.

12 The New Canadian, June 14, 1985.

13 The quick exit of Oki and Imai was witnessed by Yuki Mizuyabu and others who were near Eggleton’s office at the time, waiting to meet with him and the MCCR. Mizuyabu, Yukihara. [Personal Journal.] 28 May 1985.

14 Roy Miki to NAJC Council members, Winnipeg, 12 April 1985. Miki wrote “…the Toronto JCCA are no longer carrying out, even minimally, the responsibilities and duties of Council members. In particular, they have refused to distribute the NAJC Newsletter to their members, or to allow the NAJC to do the mail-out using the membership list.”

15 Imai, George. “A Banquet of Shame The Expulsion of The Toronto JCCA", The Canada Times, December 12, 1985.

16 March 1986 national poll results, announced by the Ad Hoc Committee for Japanese Canadian Redress on April 10, 1986.

17 Ernie Epp to Jack Oki, Ottawa, 6 June 1985.

18 The Ad Hoc Committee of Concerned JCCA Members was co-chaired by George Kadota and Stum Shimizu. Through this committee, members searched for legitimate ways to have their voices heard by the Toronto JCCA chapter.

19 The New Canadian, July 18, 1986.

20 Mizuyabu, Yukihara [Personal Journal.] 5 July 1986. 207

21 According to the Toronto JCCA executive, parallel membership in the NAJC not only prevented one from being on the board of the Toronto JCCA; it automatically terminated one’s general membership. This appears to be a rule that was made up as they went along. It cannot be found anywhere in the Toronto JCCA Constitution of 1961.

22 Mizuyabu, Yuki. [Personal Journal.] September, 1986.

23 Mizuyabu, Yuki. [Personal Journal.] 5 July 1986.

24 Takeo Arakawa came to Canada in 1926 as a young man. After the war, he started the Trans Pacific Trading Company, one of the most successful Japanese Canadian enterprises, employing over 100 people. The New Canadian, November 2, 1984.

25 NAJC Newsletter, January 1987.