Chapter 4

The 1977 JC Centennial

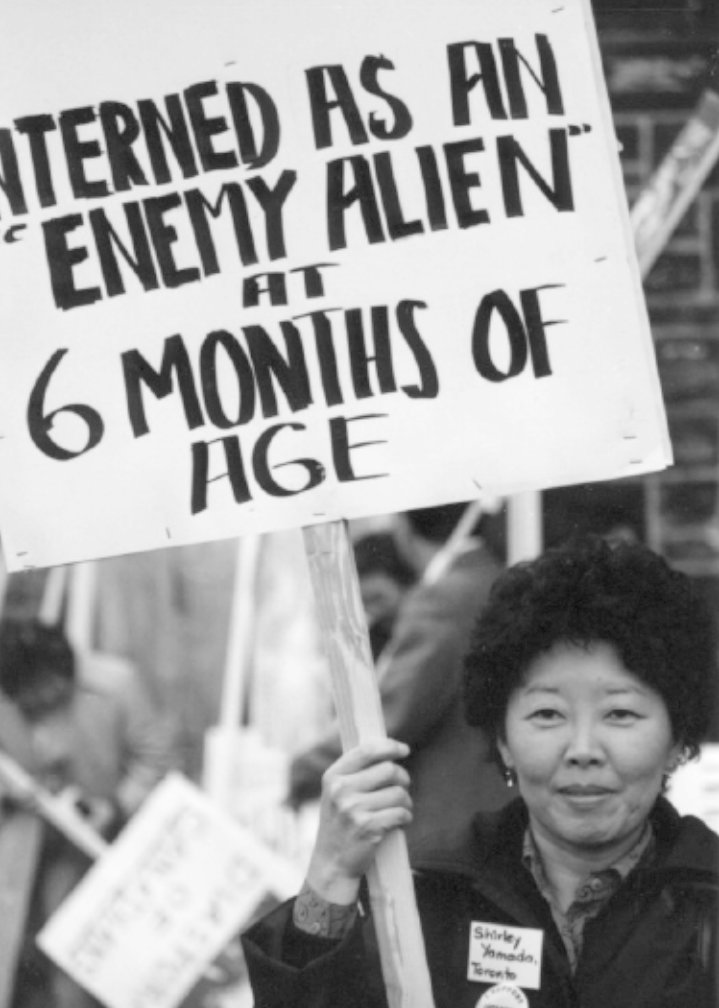

By Shirley Yamada

In the fall of 1975, Toyo Takata1 brought a proposal to the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA), the national organization representing the Japanese Canadian community. Takata proposed a year long, national centennial commemoration of the arrival of the first immigrant from Japan, Mr. Manzo Nagano (1854-1924).

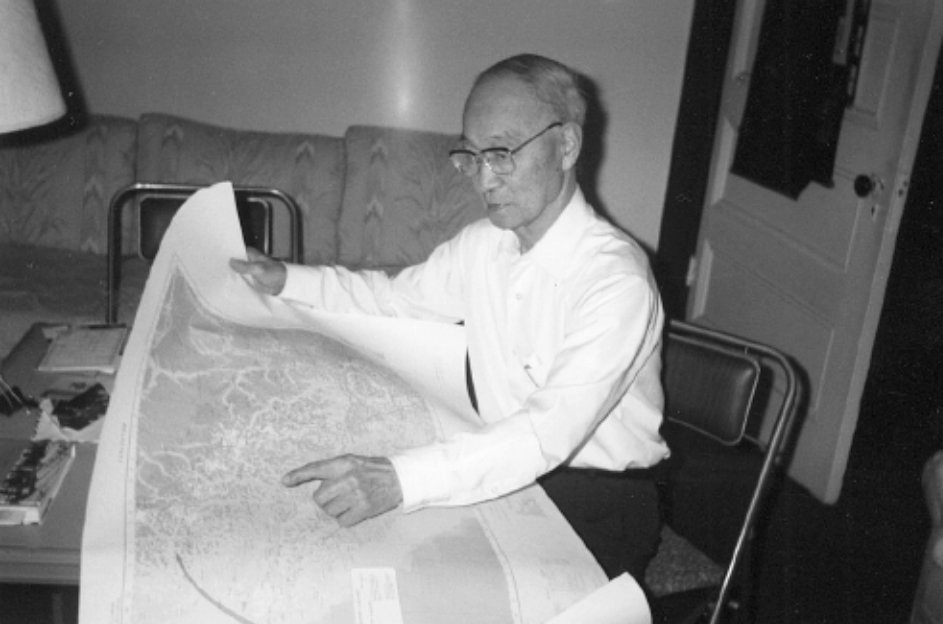

“Manzo Nagano might have ended up in the United States or Britain or almost anywhere. When this bold young adventurer [from Nagasaki] stowed away on a British ship…in 1877, he had no idea of its destination. But the ship docked at [New Westminster] and Nagano stepped into history…”2 Arriving 12 years before the establishment of the Japanese Consulate in Vancouver, Nagano settled in Victoria and became involved in various business enterprises, including a hotel for Japanese immigrants. Eventually, he returned to Japan where he died at the age of 71. As the first known Japanese person to step foot on Canadian soil, Nagano became a symbol of the Japanese presence in Canada. Thus it is fitting that a mountain in the Rivers Inlet region of beautiful British Columbia was named in his honour around the time of the JC Centennial. Over the years, several Japanese Canadians, such as Randy Enomoto, have climbed to the top of Mount Manzo Nagano.

Nagano led the way for thousands of his countrymen who dreamed of a land where they might, through sheer hard work, earn enough to return to Japan in relative wealth. The issei generation endured decades of grinding labour, racial discrimination and loneliness in the new land. “Coming here mainly from 1895 to 1925, they cleared virgin land, cut timber, dug for coal and helped build the railways that opened up Canada.”3 Then their children, the nisei, were born. The nisei grew up knowing Canada as their only home. Manzo Nagano, like many other issei pioneers, ended up staying here for many years. He did not return to Japan until the later years of his life.

The Japanese Canadian Centennial of 1977 gave us an opportunity to point out the substantial contributions of our issei forefathers to the economic development of Canada, especially in British Columbia. Our parents and grandparents not only helped build the railroad alongside Chinese labourers, but also developed the fishing industry, agriculture and forestry in B.C. Their contributions needed to be acknowledged publicly.

After 35 years of struggle to regain a footing since the expulsion, the Japanese Canadian community was ready to celebrate its 100 years of tumultuous history. Here was a chance to restore our dignity as Canadian citizens and to update the rest of Canada who may have lost sight of our community once the war was over.

It soon became apparent that such a nationwide celebration would require a national organization to coordinate the numerous events. The organizing committee in Toronto therefore established the National Japanese Canadian Centennial Society (NJCCS). Our first executive body included the following individuals: Toyo Takata (executive director), Roger Obata (national chair), Tami Marubashi (co-chair), Sam Nishiyama (national treasurer), Toshi Oikawa (recording secretary), Denise Nishimura (corresponding secretary), Susan Hidaka (public relations) and George Imai (government contact coordinator). There were 13 other members on the national executive, plus representatives from each participating province.

It should be noted that the National Japanese Canadian Centennial Society could obtain charitable status, while the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association could not. Receiving a charitable donation tax receipt was an added incentive for those who wished to contribute to our budget.

Corporations and individuals donated generously to this colourful, non-controversial celebration of our heritage. The largest amount of funding came from the Secretary of State’s Multiculturalism Directorate. Without the financial backing of the federal government, national projects such as the Historical Photographic Exhibit and National Odori Concert would not have been possible. We owe a special thanks to the late Dr. Richard Young of the Multiculturalism Directorate for his continual support of our project.

On January 4, 1977, a press conference was held at the Hotel Toronto to announce the Centennial to our fellow Canadians. The Globe and Mail followed up with an editorial, which said in part: “Canada has not always been properly grateful for the contributions of the Japanese to its mosaic culture; nor have the early struggles of the pioneer issei (first generation) been accorded the admiration that is their due. The Centennial being observed in 1977 offers a great opportunity to find out what some of us may have been missing.”4

“So You’re Nancy’s Daughter!”

As a sansei who did not know a single person of Japanese descent in Toronto, the JC Centennial of 1977 proved to be a turning point in my life. I had a few relatives scattered about Ontario, but my mother had died many years before, and my father had gone to live in Japan when he retired. In the spring of 1977, I saw an ad for secretarial help in The New Canadian and I applied for the job.

The interviewer was Roger Obata, one of the executive members of the JC Centennial Society. He asked me to meet him at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC) on Wynford Drive. Roger greeted me in the parking lot and one of the first things he wanted to know, of course, was where my folks were from. He meant “before the expulsion”. When I mentioned that my mother was from Prince Rupert, his face lit up. Prince Rupert was his hometown. The next question was inevitable: “What was her maiden name? And then, “So, you’re Nancy’s daughter!” Twelve years after her death, I was meeting someone who knew my mother from high school days.

Over the next years I was to meet several more Japanese Canadians through my work on the JC Centennial project. The entire year of 1977 was devoted to a cross-cultural celebration of the Centennial of Japanese Canadians—and I was to become an active participant. It was a wonderful year of discovery for me, the discovery of my community and my Japanese identity.

Spirited Edy Goto and I worked hard in the tiny back office of The New Canadian. The owner of the paper had kindly turned over this space to us for a few months. Under the supervision of Roger Obata, we put out newsletters to keep in touch with all the regions and branches across Canada. Looking over these newsletters now with my middleaged eyes, I wonder how anyone could have read such tiny print, an impossible 8-point font at most! All in the name of saving postage costs no doubt, as there was a lot of information to share.

Takashima and LaPierre in Hamilton

Aside from working on the newsletters and taking minutes at board meetings, I also attended various cultural exhibitions and conferences through my involvement in the Centennial Society. These experiences brought me in touch with a whole new world of people and taught me a lot about the history of my community.

One conference, held at McMaster University in Hamilton on April 23, 1977, tackled the serious and controversial subject of the War Measures Act. This act had violated the human rights of three ethnic minority groups in Canada: the Ukrainian Canadians in 1917, the Japanese Canadians in 1942 and the Québécois in 1970. Panel members discussed the invocation of the act during the FLQ crisis in Quebec, a crisis that was still relatively fresh in our minds. Television journalist, Laurier LaPierre, provided some insights from the people’s perspective. He explained how the Québécois singer, Pauline Julienne, wrongfully incarcerated, sued for compensation and won. The sum she presumably requested and was awarded, one dollar, was not important. But the possibility of suing one’s government for a political injustice and actually winning spoke volumes to us as Japanese Canadians. It was an inspiration that gave us the impetus to pursue our struggle for a formal apology and monetary redress.

Shizuye Takashima, artist and author of the children’s book, A Child in Prison Camp, was another memorable speaker at the Hamiltion Conference.5 She spoke movingly of her childhood prison camp experiences in New Denver, B.C. I marvelled at her courage in opening her heart and exposing such painful memories to the world. During the question and answer period, emotions overflowed. One angry man even threatened to write to Queen Elizabeth as a last resort for some sort of acknowledgement or redress of the past injustices. It was the first time I had witnessed such an outpouring of emotions over our history. I was shocked and excited to learn that my father’s railing against the Canadian government throughout my childhood was not unique.

The April 1977 conference was probably the largest public gathering of our community that I had ever attended. I discovered many interesting, intelligent, funny and generous Japanese Canadians. I had come to the conference by bus. My seatmate was Sid Ikeda, long time president and executive member of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre. My newfound enthusiasm at being in the company of so many Japanese Canadians must have prompted me to gab on and on relentlessly. Sid loves to tease me, recounting how I bent his ear during, what for him, was an interminable bus ride. It was probably at this Hamilton conference that Toshi and Nobu Oikawa took me under their wing, inviting me to sit with their group during a break. And I believe it was Denise Nishimura who kindly gave me a lift back to Toronto.

Another highlight for me was a mid-May weekend when Reverend Paul Nagano—yes, grandson of the first Japanese immigrant, Manzo Nagano—participated in some JC Centennial activities. He conducted an interfaith service and held stimulating discussion groups with young people in Toronto. The past was beginning to catch up to the present.

As spring rolled into summer, the number of Centennial events soared. It seemed that every town with a handful of JCs held a Heritage Day or a Folk Arts Festival—or a Japanese Canadian Week. Bryce Kanbara and George Yamada produced a JC Centennial calendar with all the events scheduled across the country marked in gold. Some 33 events were noted but, by year’s end, an estimated ten times that number of projects and activities had taken places.

Saturday, May 14, 1977 was designated as “Centennial Day” across the country. Japanese Canadians set aside this day for dedication ceremonies and special dinners attended by government representatives. Toronto’s Centennial celebrations were officially launched the evening of May 14, in the grand ballroom of the Prince Hotel. A crowd of 400 people poured into a long foyer lined with hundreds of photographs set up under Roy Shin’s supervision. There were cries of surprise and recognition as they pointed out to each other their faces among old pictures taken at school, social gatherings and places of work. Interspersed with these happier photos were ones conjuring up instant memories of the racist climate during the war years.

A standing ovation greeted the head table guests as they filed into the banquet hall which had been decorated with banners and flags showing the Centennial symbol and a huge cake ringed by 100 tiny Centennial flags in the centre of the room. The guest speaker was Senator David A. Croll. He informed the audience that he had already made his apology to the Japanese Canadians on April 24, 1947, when he said the following in the House of Commons:

I hang my head in shame before my comrades in arms of Japanese ancestry. As a member of this House I can neither forgive nor justify the wrong that has been done to a blameless people. As a firm believer in democracy I must say that I think we betrayed the fundamental principle of democracy, which I consider to be equality. In Canada there is no room for the doctrine of white supremacy, nor is there any room for second-class citizenship. I only hope that my country will never again put me in a position where I have to stammer forth s6ome sort of explanation for the action, which the Government has taken.6

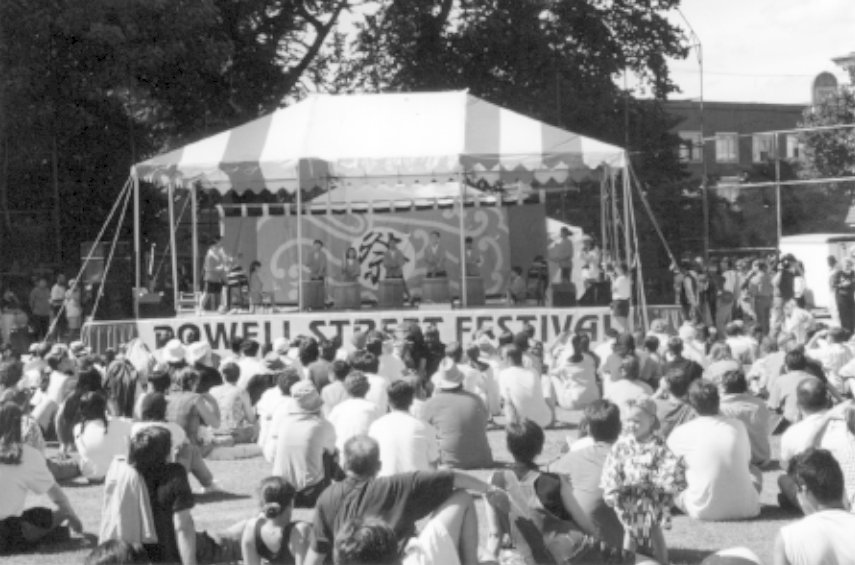

One of the objectives of the Centennial was to create permanent symbols of our contribution to Canada. Many Japanese communities presented their towns, cities and provinces with commemorative gifts, which would benefit all citizens. These included the Powell Street Festival in Vancouver, which became an annual event, and Yuko Gardens in Lethbridge, Alberta. The Japanese Canadians of Ontario gave the province a beautiful temple bell, which is located at Ontario Place in Toronto and serves as a permanent reminder of our Centennial. It is still rung every New Year’s Eve. The late Ken Adachi’s definitive history of the JC expulsion, The Enemy That Never Was, was also considered a special JC Centennial project.

Many of our issei received special attention throughout the year. The Centennial Society nominated one issei for the Order of Canada. Two years later, in 1979, Takaichi Umezuki, publisher of The New Canadian, became a Member of the Order of Canada.7 His citation reads, “Publisher of The New Canadian, a Toronto newspaper printed in Japanese and English. For nearly sixty years he devoted himself to the welfare of Canadians of Japanese origin and still acts as spokesman for their senior citizens.”

Events such as obon celebrations, picnics, dances and social teas proliferated. Centennial fundraising raffles, photo contests, walkathons, cookbooks, phone directories, a ham radio project, poetry anthologies, a tour of the Buddhist churches of Western Canada—even a Japanese Canadian bonspiel—and on and on it went. All of this took place out of our tiny population of 40,000 scattered across this vast nation. I had heard it said that there were more people from Iceland living in Canada than Japanese Canadians living in Canada. True or not, I used that “statistic” to emphasize our miniscule population. You may see other Asians around Toronto, but they are most often of Chinese, Korean or Vietnamese ancestry. We’re a tiny, tiny group. A rarity. A jewel.

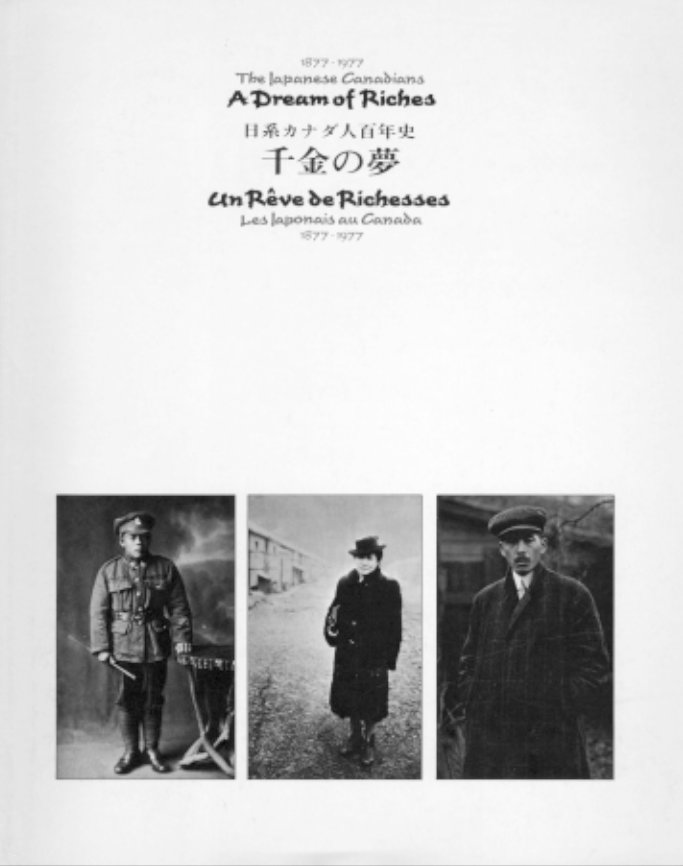

One of the major touring projects was the Historical Photographic Exhibit: “The Japanese Canadians 1877-1977”. The exhibit, mounted by Vancouver’s Tamio Wakayama, drew large crowds across Canada and Japan. The exhibit was permanently recorded in A Dream of Riches, a beautiful, sepia-tinted catalogue, which completes our few, treasured family photographs, lost, trashed and abandoned at the time of the JC expulsion. The photographs, accompanied by text in English, French and Japanese, allow us the opportunity to see the issei and nisei as they were—serious, contemplative, hard working and with brief respites of playfulness. Like many sansei, I was deeply moved by the photo exhibit because it heightened my understanding of my parents and grandparents. A picture is indeed worth a thousand words.

Unravelling the Past at Lake Scugog

Summer camp brought more learning experiences for me, some of them painful. Koyu Camp on Lake Scugog in British Columbia was meant to provide a once-over-lightly introduction to traditional Japanese arts such as ikebana (flower arranging) and sumie (Japanese style brush painting). The oldest girl attending was 16—aside from me, that is. I was 36 that summer. Casting aside any feelings of embarrassment, I attended as a camper in order to learn. I knew so little about my culture. Meanwhile, the other adults were occupied with looking after the education and care of dozens of young people.

One lesson dramatically explained what it was like to be Japanese Canadian during the traumatic times of World War II. It was the first time I had seen an Enemy Registration Card and I believe it was Mae Ogaki’s. I realized that my parents would have been forced to carry this I.D. although I had never seen theirs. During the presentation, Art Kobayashi suddenly broke a piece of glass with a stone. The impact brought home in a second how it must have felt to be on the receiving end of a hate-hurled rock through the window of one’s home. How did such good, gentle people, most born and raised in Canada, become branded “enemy aliens" of a country, the only country they knew as home?

Memories came flooding back. My mother standing there with her tin plate, lining up for food in Hastings Park. Then I was back in the mid-50s. My father is coming home late at night followed by taunting, young hakujin (i.e. white) men. They shout ugly epithets in the still air. My “issei” father responds in broken English. My mother was undoubtedly angry at the disturbance—and embarrassed. “What will the neighbours think?” I was mortified, period. In retrospect, I admire my father’s anger and courage for not letting the insults go unchallenged. I realized his spirit had not been entirely broken. His tiny triumph—too late to tell him so now.

The Birth of the Redress Movement

Looking back at the various events of the JC Centennial, I see it as a wonderful time of self-discovery. We met each other at workshops and seminars on identity crises, interracial marriage and multiculturalism. The Centennial facilitated the inclusion of any Japanese Canadian who wanted to “make contact” with the community. It allowed opportunities for personal growth for those already active in the JC community. Perhaps for the issei, the year’s events induced nostalgia for the past and the familiar things they knew—bittersweet memories of where they had come from and how they had lived out their lives. And for the nisei and the sansei, perhaps the Centennial helped to restore a healthier level of pride in their Japanese heritage. Perhaps it was a jubilant Japanese Canadian form of the African American “Black is beautiful” movement during the 1960 and 1970s.

Was there a way to identify one’s self with the Japanese Canadian community without setting aside our “Canadian-ness"? For me, my sense of cultural identity was perfectly symbolized by the JC Centennial logo designed by Art Irizawa: a five petalled sakura (cherry blossom), containing at its heart the Canadian maple leaf. I believe it epitomized the two cultures, distinct but each part of the other. I wish that we had had this symbol long ago. It carries much more dignity than the banana symbol that many of us were stuck with while growing up. I would guess that few of us escaped “bananahood" for at least some part of our lives. But that was quite understandable given the circumstances. More compassion than derision was called for.

The 100th anniversary celebrations opened a window to experiences previously unknown for many sansei. Since most nisei parents wanted to forget their traumatic memories of the expulsion and imprisonment, it was not easy to elicit details about the past. In many Japanese Canadian families it was a forbidden subject, a subject that managed to stir up too many buried emotions. It took the Centennial to inform these sansei of the terrible treatment that their parents and grandparents had been subjected to by their own government during the war. The pioneer issei and nisei did indeed suffer. To further rub salt into their wounds, they had no means to express their feelings, nor had they received acknowledgement for their travails. The Centennial recognized their sacrifices and struggles for us, the younger generations. Many Japanese Canadian communities held a keiro kai (i.e. a celebration to honour the elderly issei.) All seniors were given honorary membership in the Japanese Canadian Centennial Society and presented with a gold membership pin. They also received a specially made commemorative teacup inscribed in Japanese with the following verse:

In land of the maple leaf, Japanese Canadians proudly celebrate their centenary.

(translated)

As 1977 drew to a close, it was time to take stock. The community events of 1977 nurtured a sense of cultural pride and an empathy with the issei and nisei. Distilled over time, these feelings culminated in the questions, “Why did our parents and grandparents have to suffer so unjustly during the war and what, if anything, can we do about it now?” With this newfound knowledge—and the intelligence and self-esteem needed to act on that knowledge we were now girded to do battle. This was the ultimate legacy of the Japanese Canadian Centennial. It marked the birth of the Redress movement, a movement whose time had come and could not be stopped.

***

Fast Forward to September 22, 1988: I did it for you, Mom, standing there with your tin plate, lining up for food like a common criminal in the Hastings Park concentration camp. I did it for you, Daddy, emasculated and helpless, as I cried, no longer recognizing you after your long absence working on a forced road gang. I did it for you Auntie, dying a few months short of Redress, too early to receive the apology so richly deserved after your ordeal. Are you pleased with my efforts? Did I do okay?

Remembering the Nikka Festival Dancers

By Sadayo Hayashi

When I was first approached to express my thoughts on the Japanese Canadian Centennial, I was overcome with emotions. As I gazed through my photo albums and news clippings, my heart filled with emotions as memories of my childhood, adolescence and early adulthood vividly came to the surface.

My family was deported to Japan in 1947, when I was only seven. Postwar Japan was a place of great upheaval and poverty. But my grandparents had a farm in Wakayama so at least we had food. My parents also managed to skimp and save to send my sister, Chiyoko, and I to an odori school. We studied there for five years with an excellent teacher. After returning to Canada in 1952, we continued to develop our odori skills by performing at local events. Chiyoko eventually started her own odori school in B.C., while I moved to Toronto to pursue nursing. But I never abandoned my passion for odori.

In 1975, Toyo Takata approached me to organize a dance group to perform something different from the usual minyo to celebrate the JC Centennial. In consultation with Ted Hayashi, Irene Tsuijimoto, Harumi Nakamura and Chiyoko Hirano, we created a national dance troupe called The Nikka Festival Dancers. It included around 30 sansei performers from B.C. and Ontario. I was appointed National Director and Chiyoko was the National Choreographer. We also had a staff of kimono dressers, make-up artists and hair stylists.

Our most memorable performance was at the Ottawa Civic Centre for a multicultural concert involving the participation of several ethnocultural groups who worked to build this nation. Our program began with classical dances like the sambaso, evoking the image of cherry blossoms, and progressed to original Canadian influenced dances, symbolized by the maple leaf. The entire performance, including the closing dance, “Wonderful Canada”, was performed in front of Queen Elizabeth in a Command Performance. It was a great honour to perform for the Queen and a wonderful climax for the Nikka Festival Dancers during our Centennial. This performance was the culmination of two years of effort on the part of many people. Performing before the Queen was like being on a cloud, but the most gratifying and valuable reward was witnessing the joy and pride on the faces of our issei parents and grandparents. Nikka Festival Dancers vividly demonstrated the remarkable contribution of Japanese Canadians in the performing arts. We developed a network of odori performers across Canada who received professional training at various workshops. Thus, we went far in helping to revive and perpetuate an important part of our cultural heritage. As I look back on that fabulous year, 1977, I often wonder how we ever found the time and energy to accomplish so much. The driving force for me was the chance to repay my parents for their sacrifices for us in war-torn Japan. The Centennial gave many nisei and sansei a chance to say “thank you”.

I can say, in retrospect, that my involvement in developing a “Japanese Canadian odori” style helped me forge a cultural identity. One’s heritage is an integral part of one’s sense of self. Philosophy and attitude also contribute to one’s identity and art is a symbolic expression of that identity. In the art of dance there is a distinct difference between Eastern and Western traditions, especially in the movements. In my view, Eastern culture is associated with the earth and an appreciation of natural beauty—and sliding and controlled movements symbolize this. I associate Western culture with the sky, heaven and an appreciation of freedom. Correspondingly, the movements of jumping and stretching are more characteristic of Western dance. With the Nikka Festival Dancers, I aimed at a harmonious blend of these two styles. Therefore, the dances that we performed could be viewed as symbolic of the sansei identity.

The JC Centennial of 1977 was instrumental in establishing a sansei identity. Most sansei whom I knew used to see themselves as “Canadian” only, but through their involvement in JC Centennial activities, they became aware of their rich Japanese legacy. And it was during the Centennial that the nisei and issei opened up their hearts about their ghost town experiences, allowing us to get a glimpse of their long suppressed emotional wounds. When I learned more details about the losses my parents suffered, I felt angry and outraged. As the Redress movement gained momentum, I welcomed the opportunity to support the struggle. Many of my sansei friends felt the same way.

Nikka Festival Dancers

SHIRLEY YAMADA was born in Cumberland, B.C. in September 1941. Her father, Henry Iwao Yamada, was born in Hawaii, went to Japan and then immigrated to Canada in his teens. Her mother, Nancy Sumako Kanemochi, was born in North Pacific Cannery, Skeena River. Shirley spent most of her childhood in B.C. and most of her adulthood in Toronto where she taught elementary school and then community college. During the mid-1970s, she became a social activist, participating in various human rights causes. She ran unsuccessfully a number of times as a candidate for the Libertarian Party. She says that her involvement in the NAJC took up her entire life from 1983 onward. Since December 1996, Shirley has made her home in Costa Rica where she keeps busy as the vice-president of the Canadian Club. (Photo: John Flanders)

Mr. Takaaki Kitamura, an issei who was very supportive of the NAJC’s Redress strategy, points to Mt. Manzo Nagano, a mountain in British Columbia named in honour of the first Japanese person to step foot on Canadian soil. Mr. Kitamura passed away in December 1999. (Photo: Yusuke Tanaka)

Shirley Yamada as a one year old in her father’s arms (second from the right). The Kakuno family is to the left of him and Shirley’s mother is to his right. Circa 1942.

Christmas at the Yamada home, circa 1950. Shirley (front right) with her family, including her grandparents and young uncle. (Photos courtesy Shirley Yamada)

Above: “Temple Bell” at Ontario Place in Toronto, a gift to the province from the Japanese Canadians of Ontario in 1977. (Photo courtesy of Applied Photography Ltd., Toronto.)

Book jacket of Dream of Riches, the catalogue of the 1977 Historical Photographic Exhibit entitled “The Japanese Canadians 1877-1977”

EDY GOTO was born in Toronto. Her first interest in things Japanese was sparked at York University while studying film. She filmed the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre’s Haru Matsuri (or Spring Festival) and the Sakura Kai dance group. Introduction to Japanese Canadian culture began through lessons with odori teachers, Teri Otani, Irene Tsujimoto and the late Yoshiko Kono. In 1973, Edy visited Japan on a student exchange program and returned to Canada with a fervent desire to study the interesection of Japanese and Japanese Canadian art and culture. This interest naturally evolved into an interest in the JC community and issues of racism and human rights.

In the fall of 1976 she joined the Japanese Canadian Centennial Society. From a tiny, drafty office at the back of The New Canadian newspaper office, the work of dozens was done by a few—actually just Edy and Shirley Yamada. As well as being the conduit for JC Centennial news from regions across Canada, the Japanese Canadian Centennial Society (JCCS) office in Toronto published the national and Ontario newsletters and dealt with donations and requests for information from schools and interested members of the public. Edy took the valuable knowledge gained during the Centennial to the Annex, a drop-in centre for people of all ages. The Annex made information, discussion and Japanese Canadian art available to the community.

As a parent of two young children, Edy started Kodomo No Tame in the early 1980s. It was a play group for Japanese Canadian preschoolers, their parents and grandparents. According to Edy, “The time to start learning who we are starts when we are very small. Our community owes the children access to our past. The successful outcome of the Redress movement means that we can pass on a legacy of pride.” Together with her husband, Ron Shimizu, Edy attended several Sodan Kai meetings during the early days of the Redress movement.

Edy was called to the Ontario Bar in 1994. Her interests continue to be in the area of human rights and family law. (Photo courtesy Edy Goto)

Powell Street Festival, Vancouver

Photos: Terry Watada

Notes

1 Toyo Takata is a nisei whose father arrived in Canada in 1903. He edited the English section of The New Canadian from 1948 to 1952. He is the author of Nikkei Legacy (Toronto: NC Press Limited, 1983), a richly illustrated examination of JC history from early settlement to the early 1980s.

2 Official pamphlet of the Japanese Canadian Centennial Society, 1977.

3 Ibid.

4 The Globe and Mail, editorial, January 10, 1977.

5 A Child in Prison Camp, published in 1971 by Tundra Books, was one of the first works of fiction to explore the subject of the JC expulsion. As noted on the book jacket, the story, told from the perspective of a small child, captures “the nuances” that “perhaps only children, and those who can…become children again can understand…the utter helplessness of a child as it watches its parents fight for courage and dignity."

6 The New Canadian, May 20, 1977.

7 Mr. Umezuki passed away in 1989 at the age of 83.