Chapter 12

The Ottawa Rally

Based on an original manuscript by Jennifer Hashimoto

After Crombie closed the doors to further negotiation, it appeared that Redress was stalled. Strong action was necessary to keep the issue alive. The National Strategy Committee and National Council in Winnipeg determined in late 1987 that only a show of widespread public support could force the government to reopen talks and that the next step should be a rally on Parliament Hill.

The Ottawa Rally was a last-ditch attempt to use a more aggressive strategy in light of the lack of success in dealing with a string of multiculturalism ministers and in view of the expected fall 1988 election. As Art Miki told the Nikkei Voice in February 1988, “the gathering…will be a public forum to show Canadians that the Redress issue has support from millions of people from across the country.”1

Roger Obata had raised the idea for a rally and coalition as early as 1985. In a memo to the National Council members, he outlined a proposal that included soliciting support from ethnic organizations, churches, school boards, city councils and trade unions, asking for their support for a public enquiry with a campaign of public events to be launched in Vancouver moving eastward and culminating in Ottawa.2

The Toronto NAJC board remembers that the Ottawa Rally was a monumental task of last minute organization. Minutes of the October 31, 1987 Toronto NAJC annual general meeting include a report by Roy Miki in which he “stressed the importance of [holding] the Ottawa Rally in March”. Roy Miki also mentioned that a national coalition made up of prominent individuals and organizations was to be established by December as a result of developments in the American Redress movement.

At the October 1, 1987 board meeting, Roger Obata reported that Vancouver was considering David Murata, a United Church minister from Vancouver, for the position of National Redress Coordinator. The job description included organizing a national Redress campaign which would involve a) meeting with JC communities, b) meeting with nonJapanese support groups, c) lobbying politicians, d) meeting with media, 3) preparing media information kits and articles and 4) coordinating fundraising projects.3 By November 1987, David Murata had accepted his appointment and moved to Toronto. It was logical for him to set up his headquarters in Toronto since Ottawa was a short trip away. Also many of the contacts that could be made for the National Coalition, such as national offices of ethnic organizations, were located in Toronto. The National Coalition and the Ottawa Rally therefore seemed to have arisen through a combination of ideas and resources primarily from Vancouver and Toronto.

The Early Planning Stage

After the NAJC Toronto Chapter endorsed the Ottawa Rally, it was faced with its biggest project to date with only a few months preparation time. Since the JC organizations in Montreal, Hamilton and Ottawa were relatively small, Toronto was looked to as the main source of supporters. Western attendance would be limited due to the distance involved.

David Murata was in constant communication with other NAJC centres, primarily Vancouver, Winnipeg, Ottawa and Toronto. Decisions about the overall planning for the Ottawa Rally and related events were passed on to the Toronto NAJC. For several months rally preparations dominated the Chapter’s activities.

The first thing to be decided was the date. April 1, Freedom Day—the day in 1949 when the last restrictions were lifted from Japanese Canadians—would have been a preferred date. But April 1 fell on Good Friday. Thursday, April 14, was chosen instead, a weekday so that the largest number of MPs would be available at the Parliament Buildings.

The nature of the event evolved more slowly due to a combination of practical necessity and internal political issues in the Ottawa JC community. The original concept was for a placard carrying parade through downtown Ottawa and an outdoor rally with taiko drummers on a flatbed truck with members handing out leaflets, but there was some opposition from members of the JC community in Ottawa, where many JCs had civil service affiliations. This kind of event must have seemed to resemble too closely the “radical” element that the Survivors Group decried. Although they were not unanimously behind the idea of a public rally, the Ottawa Japanese Canadian Association (OJCA), led by president Tony Nabata, eventually voted to support it in light of the Toronto Chapter’s enthusiastic involvement.

Sensitive to the feelings of the OJCA members, the national office of the NAJC decided to make some changes to soften the “radical” image of the rally so that there would be no suggestion of anti-government sentiments. The NAJC Toronto Chapter minutes of February 20, 1988 reported that the OJCA wanted “the name ’Rally’ changed to ’Event’ because it ha[d] less boisterous connotations, and they also want[ed] the event to be held indoors to avoid any possible embarrassment due to the noise and banners.” The name change was made official by the Winnipeg NAJC headquarters by February 24, 1988. The “Ottawa Rally” would be known as the “National Redress Forum”.

The Toronto Chapter felt that it was important to appear united, for the media would have seized the opportunity to sensationalize any sort of internal squabbling. It was decided that media coverage of the event could still be effective despite these last minute changes and an indoor event had the advantage of better protection in case of inclement weather, especially for older participants. The new name of the event was therefore accepted for public notices, but it became a source of jokes among Toronto committee members. The bland words “Ottawa Event” and “National Redress Forum” did not convey the feeling for an event that might be the last passionate hurrah of people who had waited over 40 years for justice. Therefore, privately, most of the Toronto committee members still referred to the event as the “Ottawa Rally”.

Although slightly taken aback at the work involved in publicizing and organizing a contingent to Ottawa, in addition to fundraising and assisting David Murata, the Toronto NAJC accepted the project enthusiastically. Shirley Yamada remembers that she predicted such an event on the B.C. internment camp tour in 1987. She remembers saying on the bus: “I know that one day we’ll be marching in the streets and demonstrating…and I think everyone thought I was nuts because Japanese Canadians just don’t do that kind of thing.”4

Organization of the Ottawa Rally put a strain on the resources of the executive committee members and staunchest supporters of the Toronto NAJC for it came just after the Ethnocultural Rally of October 29, 1987, the chapter’s annual general meeting of October 31—and the 40th Anniversary banquet of the NJCCA/NAJC on November 14, 1987. Nevertheless, the Toronto NAJC executive found the time, energy and financial resources to devote to this very special project. A separate Ottawa Rally Steering Committee was established to organize the bus trip, encourage people to sign up to attend, arrange accommodations and raise necessary funds. David Murata divided his time primarily between the National Coalition for Japanese Canadians and organizing for the rally at the national level.

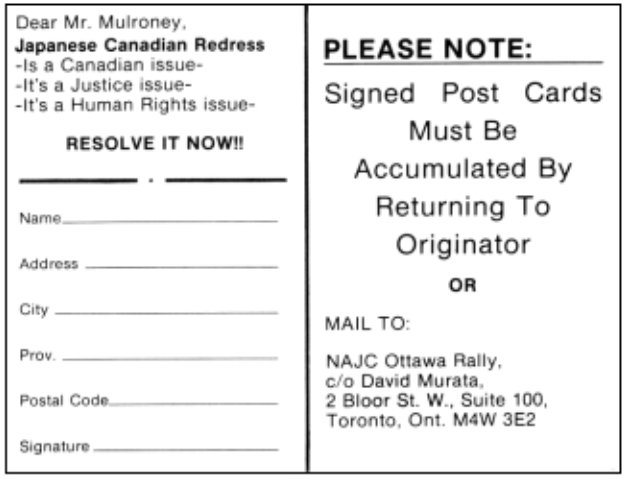

Postcards and Ribbons of Hope

As preparations developed, Toronto came up with key ideas for the rally, including the postcard blitz and Ribbons of Hope. The post card idea was simple: print thousands of postcards that could be distributed for signature and sent to Prime Minister Mulroney with a succinct message, “I am a voter. I support Japanese Canadian redress now!” This project was the brainchild of Shirley Yamada. Her suggestion was adopted enthusiastically by the Toronto Chapter and the postcard blitz was in the early planning stages by January 1988.

A total of 63,000 cards were printed and distributed across Canada. Toronto’s goal was to get 30,000 cards signed and collected. The returned cards poured in and had to be cleared from the downtown Toronto post office box three or four times a week by Van Hori who delivered them to David Murata. Many of the postcards were also distributed by individual NAJC members who explained the Redress issue to coworkers, neighbours and friends. Sometimes the reception was cool, but the warmth and generosity of strangers was on occasion overwhelming. Yuki Mizuyabu, in charge of Toronto distribution, recalls that Norman Oikawa was calling for more and more postcards and distributed 6,000 by himself, going door to door through southern Ontario. Doctors and dentists who supported us kept supplies of postcards in their offices and asked their patients to sign them. Photocopies of all the postcards were sent to Addie Kobayashi who input the names and addresses into a master list. These postcards helped enormously in spreading the Redress cause into the non-JC community and creating a sense of involvement within the JC community.

Toronto became the main centre of activity during this hectic time, but David Murata also kept in touch with other centres across Canada through Art Miki’s office in Winnipeg. And he was always in close contact with the rally organizing group in Ottawa. He went back and forth between Toronto and Ottawa, often staying with Mas Takahashi, and working with people like Amy Yamazaki or Aki Watanabe in Ottawa to finalize arrangements as to media coverage, the pre-rally banquet, speakers and other details of the indoor “forum”.

Although most of the planning and fundraising took place in Toronto, other chapters of the NAJC were also actively involved in drumming up support for the rally. Close to 70 people attended a public information meeting in Montreal on February 1, 1988, sponsored by the Quebec NAJC. Speakers included Audrey Kobayashi, then president of the Quebec Chapter, and Yosh Taguchi reflecting on conversations held with community members during their recent fundraising telethon.

It was at this February 1 meeting that an issei named Shigeru Kido stood up and said: “For many of us older people, this may be our last chance to ask the Canadian government to acknowledge the injustices we suffered during World War II. My colleagues and I will participate as much as possible; however, for some of my friends, the cost is prohibitive. I wonder if there is any way for the Japanese community here in Montreal to enable all the older people who would like to go to Ottawa to have this last opportunity to make an impact.”5 In response to Mr. Kido’s plea, Christine Hara headed a committee which organized a fundraising dinner. As a result, more issei from Montreal attended the Ottawa Rally than issei from any other geographical region.

By February 1988, the NAJC Redress Committee was devoted exclusively to the Ottawa Rally and meetings were held every two weeks. The Toronto Chapter’s Ottawa Rally Committee was comprised of David Murata as chairman, Dennis Madokoro, Roger Obata and Shirley Yamada on publicity, trip coordinator Ken Noma, fundraiser Van Hori, registration Van and Addie Kobayashi, signs Bill Kobayashi. However, most of the executive and other staunch NAJC supporters devoted enormous amounts of time to the rally: Ko and Yae Ebisuzaki, Stum Shimizu and Jennifer Hashimoto who helped with fundraising. Matt Matsui was also a tremendous help in arranging the bus banners, banners that had to be waterproof and made of strong enough cloth to go on the outside of the bus. Ben Fiber and Joy Kogawa contributed a great deal to the success of the rally. Their contacts outside the Japanese Canadian community were extremely useful in obtaining names for the National Coalition.

Publicizing the event, given the short notice, was essential. The rally was to be covered in union publications and mainstream periodicals. The National NAJC also hired Jesse Nishihata to film the rally and several information meetings were held to raise public awareness of the event. Since David Murata’s father, Ben, was the minister of the Japanese congregation at the Centennial United Church on Dovercourt Road, the meetings were held there.

Van Hori recalls that after one meeting, they realized they did not have enough people registered so “David [Murata] said we should send out a Chapter newsletter right away and I said, ‘Good idea, let’s send out a Chapter newsletter.’ And then after the meeting was over, David said, ‘Well, let’s get working on it!’ I didn’t expect him to say he wanted it out the next morning. So we worked on it around the clock until seven in the morning. That was about the fastest Chapter newsletter we had ever gotten out…It was a mess, but it got out [the next day] and that’s the one that has the form on the back that said there was a ribbon of hope and that if you wanted to donate…”6

Originally, it was estimated that three busloads of supporters would sign up from Toronto and Hamilton. This estimate seemed to have been too high, since by March 3, 1988, Van Hori advised the executive committee that only 49 people from Toronto had registered to attend the rally. Some difficulties for potential rally goers were health and the fact that April 13-14 was the middle of the week and some people couldn’t get time off work. Therefore, thoughts turned to how to involve those who supported the rally but could not attend.

Shirley Yamada came up with the idea of having yellow banners bearing names of the deceased and the names of those unable to attend the rally who wanted to share in the experience. For a donation of $25 or more, Japanese Canadians could have their names placed on what came to be known as a “Ribbon of Hope” to be carried during the rally. As it turned out, “Ribbons of Hope” was more accurate since each of the 300 names was printed on its own ribbon by Mary Murata. Shirley insisted that the ribbons be yellow for their visibility. When six-inch ribbons were discussed, it turned out that Roger Obata thought they should be small strips only six inches long and Shirley had in mind large banners six inches wide and as long as necessary for the full names on them to be visible. The yellow banners were attached to tenfoot wooden supports in the shape of a “T” so that one person carried a post fluttering with many names. The banners were a moving tribute to the Japanese Canadians who had suffered during the war years and provided a meaningful way for many Toronto JCs to “be” in Ottawa with the actual marchers. In fact, the Ribbon of Hope idea caught the imagination of JCs so much that it provided a large source of donations for the rally.

The cost of the bus trip, overnight hotel stay and banquet was set at $145. In case this cost was prohibitive to issei or anyone on a fixed income, the Toronto Chapter executive voted to reduce the cost for issei to a $20 registration fee. This meant that sufficient funds had to be raised to cover any shortfalls as it was too soon to tell how many people would sign up. The cost of the buses for the two-day Ottawa Event, including a tour of Ottawa, was $3,600. To help raise much needed funds, a successful telephone fundraising and publicity campaign was carried out by me and others in early February 1988.

As part of the fundraising effort, the Toronto NAJC held an Ottawa Rally Raffle, primarily organized by Van Hori. Since there was no time to solicit prize donations from companies, Roger Obata obtained some of the prizes at cost. Eventually, despite the short selling period after the tickets were mailed out to the NAJC Toronto Chapter members, the raffle made a substantial profit. Mrs. Fusaye Hori, Van’s mother, volunteered to use her address as the return address for the tickets. She also did a tremendous amount of work opening up the tickets and taking them apart.

The National Redress Coalition

During the period of our telephone campaign to solicit monetary donations, a leaflet entitled “Redress the Wrong: Justice in Our Time”, was produced. It set out the wartime injustices to JCs and the NAJC’s recommendations and included a list of “What You Can Do”, from writing to Mulroney to making a donation to the NAJC Redress campaign. It also included a letter requesting use of names of individuals and groups as supporters of Japanese Canadian Redress according to the position outlined by the NAJC. The main aim was to collect a list of potential supporters from the larger Canadian community for the National Coalition for Japanese Canadian Redress. It was important to show the government that support for Redress was widespread, not just confined to our small JC community.

While the National Coalition was under David Murata’s jurisdiction, he had a great deal of help from people such as Joy Kogawa, who sent out forms to many prominent Canadian writers, and Mona Oikawa and others who sent out forms and collected the responses. An interesting problem occurred during the month when the letters for the Coalition needed to be mailed out because a postal strike was going on. Canada Post was using replacement workers and the letters to the head of the postal union and other unions could not be delivered by replacement workers when labour groups had been so supportive of JC Redress. Therefore, letters had to be hand delivered, sometimes by people who did not have access to cars.

By April 1988, the success of the National Coalition was indicated by the membership of 65 organizations and over 300 individuals, including Rabbi Gunter Plaut, Shirley Carr, president of the Canadian Labour Congress, historian Ramsay Cook, musician Bruce Cockburn, artist Joyce Wieland, journalist Michele Landsberg, lawyer Clayton Ruby and authors Pierre Berton, Michael Ondaatje, Mordecai Richler and Margaret Atwood. In addition, we had the support of many wellknown Japanese Canadians such as David Suzuki, Ken Adachi, Raymond Moriyama and Roy Kiyooka.

As the day of the “event” inched closer, the Toronto Chapter held a briefing session for participants on April 5, both for those going on the buses and those going by car from Toronto and Hamilton. All the arrangements were in place. Matt Matsui had his cloth banners ready and most of the placards were ready. For the placards, Bill and Addie Kobayashi had archival slides that Jesse Nishihata had made for a presentahtion at the 40th Year Anniversary of the NJCCA/NAJC banquet the previous November. With the help of David Murata, they selected the ones they thought would make the strongest impact. Addie knew of a machine that you could use to transform a negative into a poster-size print, “a blow-up of a negative so it has sort of this eerie look to it…not exactly a clear photograph, but they made wonderful posters. Bill blew up the photos and made the frames with a stick down the middle and stapled the photos on. Since there were only 45 photos, some placards had slogans only.”7 These slogans were personal and historical, relating to the individual’s experience in the camps or as a Canadian war veteran. Van Hori had the only “loud” slogan of the 50 or so placards: “Lyin’ Brian”, referring to Prime Minister Mulroney’s promise to compensate Japanese Canadians. On April 10, 1988, the placards were picked up from the Kobayashi home in Waterloo and taken to Ottawa by David Murata in his van since there wouldn’t be enough room for them on the buses.

The Day Before the Big Day

On April 13, the bus from Hamilton started off from the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Hamilton at 7:00 a.m., making stops at Sheridan Nurseries and Sherway Mall, before the rendezvous at Scarborough Town Centre with the Toronto bus, which made a pick-up stop at Seneca College, Yonge and Sheppard, at 7:30 a.m., as had been arranged by Ken Noma.

The Ottawa Rally committee had taken into consideration every contingency. Dr. Wes Fujiwara and Dr. Misao Fujiwara, provided medical personnel for one bus. In the other bus, a nurse named Barbara Speck was in charge of medical emergencies. Shirley Yamada provided a list of chants (“Hey, hey! Ho, ho! The War Measures Act has got to go!” and “What do you want? Redress! When do you want it? NOW!”) and suggested lyrics for songs that could be sung during the march. Finally, each Toronto participant was given a kit containing a nametag, the NAJC policy statement on Redress, guidelines written by Frank Moritsugu on dealing with the media and a list of the other bus passengers. Similar kits were made for all the participants from Montreal.

As the buses rolled towards Kingston for a lunch stop, we were encouraged to share past experiences. On one bus, Bill Kobayashi started off with the story of his two exoduses—the first from British Columbia to Montreal in the early 1940s and the second one from Montreal to Waterloo, Ontario in 1979. He recalls: “That’s when René Levesque was in power. There was a language problem in the workplace and Anglophones were moving out. I always thought of that as a second expulsion…having to sell a house at distress prices…I had two expulsions…”8

Roy Sato was only nine at the time of the expulsion. He said, “When we went to Sandon, I remember thinking ‘what a place’. You could throw a stone from one mountain to another, right across the valley. The main street was built right across a river…In the winter snow piled up so much that we were able to make tunnels, forts. There we were in Vancouver garb, just rubber boots and light clothes. I think we all got frostbite…”9

The Toronto buses stopped for brunch in Kingston at the Ambassador at 1550 Princess Street, arriving at the Hotel Ramada at 35 rue Laurier in Hull, Quebec, at 2:30 p.m. They were greeted at the NAJC registration desk by Nora Nishikawa from Ottawa and Rei Nakashima from Montreal. A bus tour of Ottawa had been arranged for 3:00 p.m. and some rally attendees visited such tourist attractions as the official residence of Governor General Jeanne Sauvé.

A 5:30 banquet was held at the Palais des congrès [convention centre] in Hull, with cocktails at 4:30. The Ramada was connected to the Palais des congrès by a long passageway, which was useful since it was a rainy day. Roy Miki welcomed everyone on behalf of his brother, NAJC president Art Miki, who could not arrive until later in the evening.

Seated at the head table were the evening’s speakers: Andrew Cardoza, executive director of the Canadian Ethnocultural Council; David Kilgour, Conservative MP for Edmonton-Strathcona; Roger Obata, NAJC national vice president; Conservative MP Alan Redway; NDP MP Ernie Epp; Ottawa community representative Amy Yamazaki; NDP MP for Spadina, Dan Heap; Bill Kobayashi, president of the Toronto chapter of the NAJC, and David Murata, the NAJC’s “National Redress Forum” coordinator. The evening’s festivities began with Amy Yamazaki who gave a greeting in Japanese on behalf of the Ottawa JC community. Then respected JC educator, Hide Shimizu made a toast as the guests raised their glasses.10 David Kilgour led off the speeches by recapping the history of the Japanese Canadians, including the exclusionary laws, professional restrictions and denial of voting rights. Ernie Epp noted this was an “historic moment” to bring us here to remember wrongs done. He read greetings from Ed Broadbent.

The NAJC pre-rally banquet provided an excellent opportunity to showcase some of the artistic talent in the JC community. An art exhibit, arranged by Bryce Kanbara, was on display for all the guests to appreciate and Cassandra Kobayashi, for the Vancouver Redress Committee, launched “English Bay at Low Tide”, an original woodblock print by Takao Tanabe, an internationally known nisei artist from Vancouver Island, who was present, and who had donated an issue of 200 prints that would be used as a fundraiser for the Redress movement. They were available that night for $500 unframed.

Paul Kariya,who took over as Master of Ceremonies,11 acknowledged the World War II JC veterans. Then Alan Redway, Dan Heap, Ernie Epp and Andrew Cardoza each had an opportunity to address the dinner guests and offer their support and encouragement. David Murata thanked all of the speakers, organizations and the Ottawa community. A taiko (Japanese drum) performance, a film entitled “Images of the Last 100 Years” and songs by Terry Watada concluded the evening.

The banquet was a good build-up for the march the next day. It enabled participants to talk to the members of Parliament through their stories to reinforce the personal aspect of Redress. Rally participants mingled and delved into the past that had led them to being there. Yuki Mizuyabu recalls that as he began telling his family’s story to MP David Kilgour, about how his parents had “struggled to build a secure, comfortable life for their children and how all that was destroyed by the racist actions of our government…I was crying uncontrollably as I remembered my parents, especially my mother who was deceased by then. Even now, I cannot remember the life of my parents, which was destroyed by Canadian racism, without becoming tearful.”12

Following the banquet, several people worked feverishly to put their personal stamp on the signs, writing up their slogans on the placards in preparation for the next day, kneeling at tables in the pathway between the convention centre and the hotel. Then everyone retired to their hotel rooms to rest up for the big day ahead—the very first mass demonstration anywhere in Canada by Japanese Canadians.

Marching to Parliament Hill

On the morning of April 14, the buses loaded up for the trip to Parliament Hill. The weather was overcast and cool, and most marchers wore raincoats or jackets. The actual march had not been organized in detail and Bill Kobayashi recalls that “when we started the procession, we had all these placards…and they were all sitting there and nobody seemed to want to pick up the first placards” so he and his wife Addie and Roger Obata picked up the first placards to start off the procession. Also at the forefront were Mas Kawanami of Calgary, Charlie Kadota of Vancouver and David Murakami of Toronto. All the other marchers soon followed their lead.13

The group marched up to the Centre Block in a quiet, orderly and dignified manner. As they passed the media microphones, journalists urged them to make some noise, shout some chants. Shirley Yamada also remembers that “native people were demonstrating there too and they were in front of the Peace Tower and we had to cut right through them to get down the stairs…and they just quietly sort of parted and let us through.” There were also two other demonstrations going on at Parliament Hill at the same time, Turk and Sikh groups.

The World War II veterans in attendance, Harold Hirose, Fred Kagawa, Mas Kawanami, Jack Nakamoto, Roger Obata and Stum Shimizu, all wore berets. In fact, Jack Nakamoto had brought several for the other veterans. Fred Kagawa remembers “I went around the army surplus stores in Toronto looking for a beret to wear but they were $20 each. I didn’t want to pay $20 for a beret for a march in Ottawa. I wore my baseball cap which was bright orange.”14

The visual effect of the marchers, ranging in age from teenagers to nonagenarians, with the yellow banners standing out in the dull light and the placards with blown-up photographs, was striking. Two professional photographers captured the march and other events of the day: Gordon King, an Ottawa resident hired by the NAJC national office, and John Flanders.

The march itself did not take long, as Blanche Hyodo recalls. Blanche had driven up from Toronto with her daughter and just before the march started, returned to her car for her boots. By the time she returned, the marchers had already entered the West Block. It was a great disappointment. “I missed the rally. It was really funny after going all that way…It was a cold day and my feet were frozen and I was so cold, I thought, well, I’ll run back to my car and put my boots on…I ran all the way back, about three blocks away, and when I came back, it was all over. I couldn’t believe it…”15

Sansei Charlotte Chiba remembers: “Like an old silent movie, the marchers quietly made their way up along the winding paths which broke through the carefully manicured lawns. Issei, nisei, sansei, and even yonsei proceeded together, three or four abreast, in a long continuous line. They walked past the Peace Flame, and as they headed toward the giant oak doors of the West Block Parliament Building to the forum, a transformation was happening. Faces of old and young once carrying tentative smiles, began to bear expressions of seriousness and determination. Their steps becoming more steadfast and sure.”16

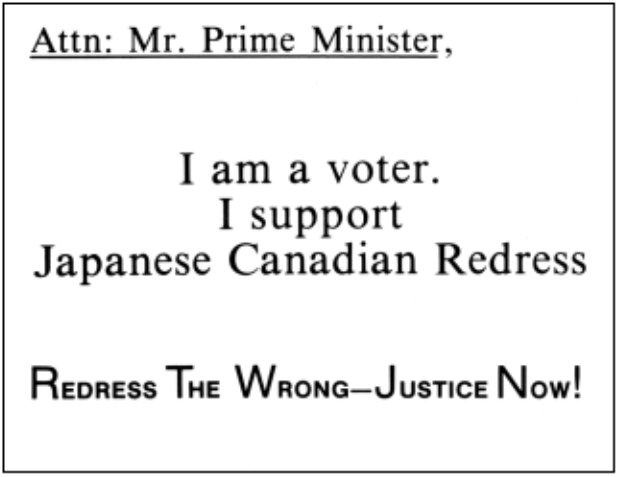

The marchers filed into the Confederation Room, Room 200 West Block of the House of Commons. The National Redress Forum, held in conjunction with the NAJC and the National Coalition for Japanese Canadian Redress, was scheduled for 11:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. As the group waited for the speakers to begin, the approximately 14,000 postcards, which had been folded in half to give a visual sense of their quantity, were spilled out onto the floor and arranged in front of the podium by Hide Shimizu. At that point, Harold Hirose of Winnipeg, a veteran in his beret, was leading the group that was chanting “We want Redress Now” over and over again. This got the crowd worked up and others joined the chanting.

A taiko performance by Wasabi Daiko members Rick Shiomi, Brenda Joy Lem and Simon Yuen opened the event. Then Terry Watada spoke about his father who had passed away the year before, noting that his father had been quiet about his experiences during the war, but “as he got older, he loosened up and started to tell me things.” Terry sang a moving song dedicated to his father called “Nisei Theme” or “The Redress Song”, which he was performing for the first time. The song, with the audience clapping along, stirred up the emotions of many people in the room.

Then Art Miki, as national NAJC president, delivered the opening speech, welcoming and identifying the issei, nisei, sansei and yonsei present. He also recognized the Aboriginal group on the program. The purpose of this event, said Art, was to impress upon the Canadian “government that there is a need to resolve this issue and…there are many people in our community who were directly affected who are passing away each day and each year.” He also mentioned the fact the case for JC Redress had widespread support among other Canadians and that educating the entire society about what happened to the Japanese Canadians was important “for the future of our country.”17

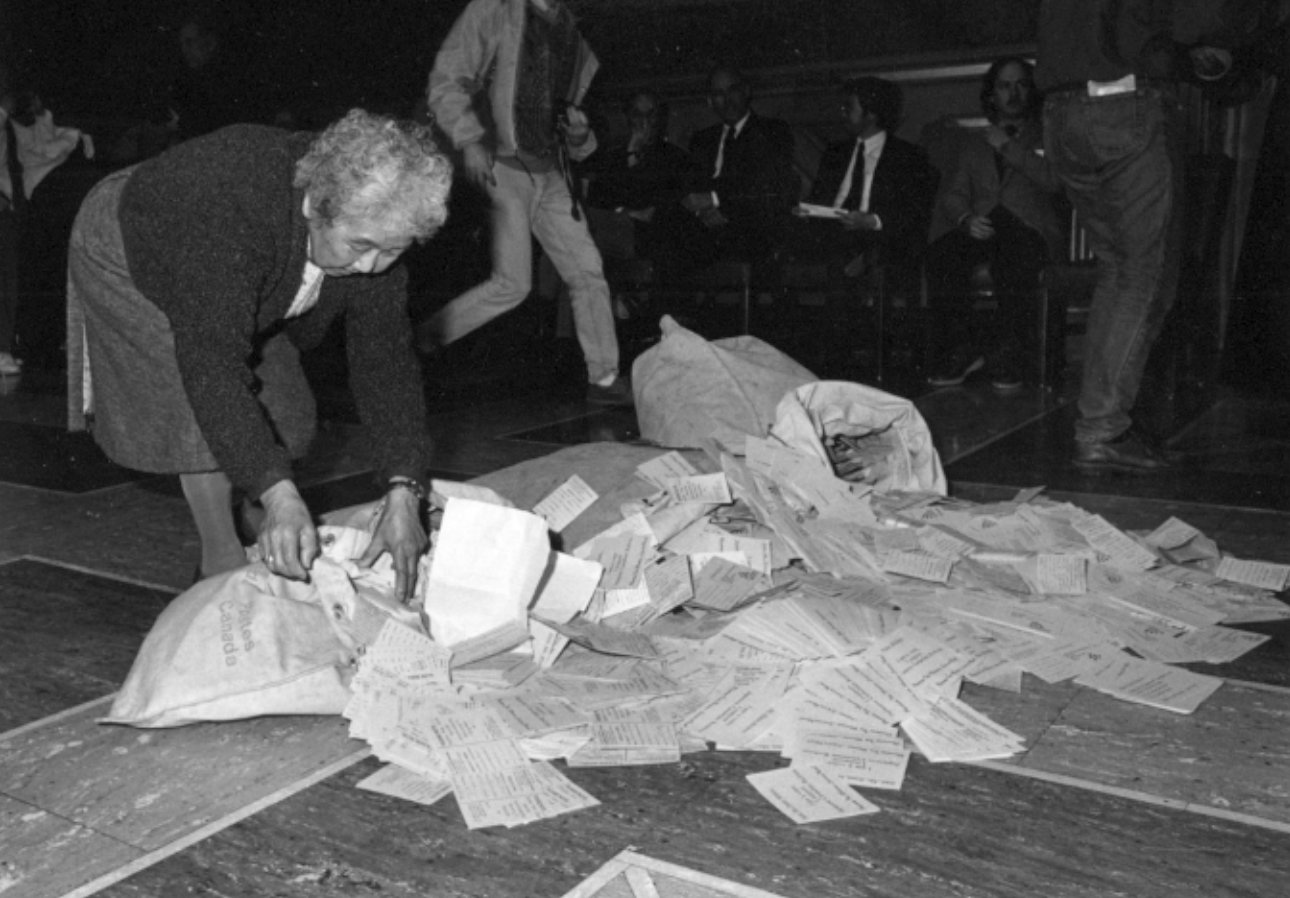

The guest speakers, invited members from the National Coalition for Japanese Canadian Redress, then followed: Canadian Ethnocultural Council representative, Lewis Chan of Ottawa, Archbishop Ted Scott of the Anglican Church of Canada, Ernie Epp, NDP MP for Thunder BayNipigon, Gilles Tardif, vice-president of the Canadian Rights and Liberties Federation, Alan Borovoy of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, Sister Mary Jo Leddy, one of the first members of the National Redress Coalition, Liberal MP Sergio Marchi, David Suzuki, the new minister for multiculturalism Gerry Weiner and Roy Miki, chairperson of the Vancouver Redress Committee.

Archbishop Ted Scott said “this event is a very emotional one for me” since he had grown up in British Columbia with Japanese Canadians and said, ’I remember children going home from school with their books, crying because they’d been told they had to be taken away…the children crying were both of Japanese origin, Canadians, and white people, friends who had been in school together…”18

No one there would forget Alan Borovoy’s dynamic speech, which ended: “We know that we cannot adequately guarantee tomorrow, but we do want to do whatever we can do. That’s why you have our support. Because it’s the only way we know how to say to ourselves, to say to you, to say to each other, to say to posterity, Never again, never again. This will bloody well never happen again!” Borovoy’s rousing speech had an overwhelming impact on many members of the audience, who gave him a standing ovation.19

Sister Mary Jo Leddy thanked the JC community for bringing the Redress issue forward despite the pain it caused to reopen these events. David Suzuki told the audience that [his] “mother was born in Vancouver, raised and lived her entire life in Canada, never went to Japan in her whole life…She died at the age of 74 and I bitterly resent that she died without ever having known an official apology for not having been an enemy…As victims of a great injustice, I also believe that Japanese Canadians assume an extra burden. We the victims know from experience the effects of racism and bigotry and so ours must be the first voices raised wherever we see prejudice rear up. Whether the bigotry is extended towards blacks, Sikhs, Jews, boat people, homosexuals or womlen, Japanese Canadians must be in the forefront against it…”20

Gerry Weiner was the second last speaker. Some were surprised that the newly appointed multiculturalism minister, who had succeeded David Crombie, was willing to attend the Ottawa Forum. Van Hori, Yuki Mizuyabu and others recall that he looked quite uncomfortable during the speeches, particularly when comments were addressed directly towards him. What was probably beneficial to Weiner’s introduction to Redress was that since he was so new to the portfolio, rather than receiving second-hand information from advisors or George Imai’s Survivors’ Group, he was hearing the facts fresh and unclouded by confusion about which JC organization to deal with. He could recognize the legitimacy of the NAJC immediately.

Weiner’s speech acknowledged the injustices of the past and expressed regret that the government and the NAJC had not been able to reach an agreement. He expressed willingness to reopen talks with the NAJC negotiating team. Roger Obata felt that Weiner had been visibly moved by the powerful messages of the speakers at the forum since he later assured Roger of his support, having a personal understanding of racial discrimination.21

As the last speaker, Roy Miki summarized the changes within the JC community throughout the Redress process—of breaking the silence, of gaining access to government files that revealed that what was done to Japanese Canadians was a political measure, nothing else. “The government fingerprinted everyone as individuals and it is absurd today, as Mr. Crombie has told us, that Redress can only be Redress if it deals with you as a community, not as individuals. No, we were treated as an ethnic community in 1942. Today, we want to be treated as individuals first, as Canadians.”22

Art Miki concluded, I believe myself that we will achieve Redress” to which an unidentified nisei in the audience shouted, “Redress now, I can’t wait for long!” Terry Watada wrapped up the event with his music.

After the Forum, the marchers picked up their placards and walked back around to the Centennial Peace Flame where many of the placards were left. Many of the marchers just stood there in the rain for a while and this memorable image was captured in photos that appeared in several newspapers. Stum Shimizu and Shirley Yamada went down to the street in front of Parliament Hill with their placards and continued marching up and down in the pouring rain to publicize Redress where they would be more visible.

The four mailbags containing the postcards, which had been folded in half to make them bulkier, were lugged over to Prime Minister Mulroney’s office by Harry Tsuchiya, Roger Obata and Norman Oikawa. Gerry Weiner himself guided them right to the Prime Minister’s secretary who assured them that the cards would be seen by Mulroney himself.

After lunch, the marchers reassembled for Question Period in the House of Commons. The JC Redress issue was understandably the main topic of debate. Unfortunately, only a few JCs were able to witness the proceedings directly because of a misunderstanding regarding passes to the visitors’ gallery. Many had to watch on a closed circuit television in a room that Alan Redway had arranged for the rally participants to use.

The Journey Home

Most of the participants went back to Toronto and Hamilton on the bus around 3:45 p.m. while some others stayed to attend a 4:00 p.m. press conference and wine and cheese reception which was being held for MPs and the media in Room 298, West Block. John Turner and Ed Broadbent were there and mingled with members of the JC community. Harold Hirose was seen actively lobbying the leaders of the opposition parties for their support. Roger Obata remembers talking with John Fraser, then Speaker of the House; “[He] said to me that he thought the Rally was an excellent way to demonstrate the sincerity of our cause. And he was all for it and he praised us for having the courage to come iup to Ottawa and mount a rally of that kind….”23

Sansei Mona Oikawa, whose late father, Ernie Oikawa, served Canada in India and Southeast Asia during World War II, summed up the feelings of many of the rally participants when she said: “I had been to many demonstrations before for different causes but I feel that that demonstration was one of the most moving…I know that my father, Ernest Oikawa, wasn’t able to attend. He wanted to go but he felt he couldn’t walk, but when I saw Roger holding the placard for the vets, I was so happy because I felt my father was there in spirit and we were doing this for all the people who had been interned and it was a beautiful thing for me to see and experience.”

No one on those buses would forget the events of the trip home. In the original arrangements, the Chinese Palace in Kingston had been booked for dinner. However, due to a last minute change in the route, another restaurant, the Golden Dragon, was booked, but David Murata had forgotten to inform the Chinese Palace and the passengers on the bus about the sudden change. It was raining and the buses were on a tight schedule so the Chinese Palace restaurant had been asked to prepare for the large group by a certain arrival time. Yuki Mizuyabu’s daughter, Lilian, who was a student at Queen’s University in Kingston at the time, had arranged to meet her parents for dinner at the Chinese Palace.

As Yuki Mizuyabu remembers the mishap: “As the bus stopped in front of the restaurant, my wife and I noticed that the name of the restaurant, Golden Dragon, was different from that in the printed itinerary. We reasoned that it must have recently changed its name. However, when time passed and my daughter did not arrive, we enquired and found that the stop over restaurant had been changed. I asked for the use of the restaurant’s telephone and called the Chinese Palace. She was there. Moreover, the restaurant had closed itself to the public and was waiting for our group to come there. My daughter sounded frightened. She felt she was being held as a hostage until our group went there to eat the food [that had been] prepared for us.” Lilian told her father, “I don’t think they’re going to let me go!”

Van Hori and Ken Noma drove to the Chinese Palace to rescue Lilian and settle the matter. Because the food had already been prepared, Van and Ken agreed to pay for the uneaten meals and they ended up with several styrofoam containers filled with breaded shrimp which they ate for several days until they were sick to their stomachs. Later David Murata offered to personally reimburse the Toronto Chapter for the cost of the food, but his offer was refused.

After the restaurant misadventure, the buses finally returned to the Scarborough Town Centre at approximately 10:30 that night. Unfortunately, the banners had to be left in the bus because no one had a car there. The banners were never recovered from the bus terminal.

Assessing the Rally’s Impact

What was the significance of the Ottawa Rally? Japanese Canadians had gone public in the most visible way, by marching on Parliament Hill. They had heard respected religious and civil rights leaders, politicians and journalists acknowledging the suffering of the Japanese Canadians and commending their courage in addressing their past and working for a better Canada. As Alan Borovoy said at the Forum: “This campaign is not parochialism by Japanese Canadians—it is social justice for everybody.”

Shirley Yamada remembers, “I have a picture of Roger [Obata] and Maryka [Omatsu] and myself and somebody else and we’re lined up and…we’re all wearing navy blue trench coats. What’s Japanese Canadians’ favourite colour? Navy. So we looked pretty conservative, nobody was wearing wild plaids or anything,” dispelling the image of the NAJC as “radicals”. Shirley also feels that the Ottawa Rally “gave a new sense of empowerment or self confidence to people who had never ever carried a placard in their lives and I think it just added a little something like, hey, I actually did this, I actually demonstrated on Parliament Hill. That is really something for quiet, introverted Japanese Canadians.”24

The Toronto NAJC held a public meeting on May 28, 1988 at the Centennial United Church, organized by Jennifer Hashimoto, Yuki Mizuyabu, Yo Mori, Roger Obata and Bill Kobayashi, to review the Rally with photos and a 45-minute video. Van Hori, Ken Noma and Yo Mori helped set up the VCR and equipment for the meeting. Hide Shimizu hand-printed the Ribbon of Hope names on a yellow background for display, since the originals had to be left behind. Roger hung a framed Tanabe print and Charlotte Chiba and Shirley Yamada looked after the sales table items. Hide Shimizu organized the refreshments. Ken Noma gave the president’s message on behalf of Art Miki and Charlotte Chiba gave the National Council meeting report. Dennis Madokoro was the MC for the evening. Other speakers included Roy Sato, John Karatsu and Joanne Sugiyama.

For those who had not been able to attend the rally, the video alone could not quite capture the elation and spirit of marching on Parliament Hill. Yuki Mizuyabu notes that the late Mr. Takaaki Kitamura had registered for the Ottawa Rally, “but at the last minute he was suddenly taken ill and could not come… The night before the trip, he was hospitalized and then underwent a serious operation. To this day, he regrets that he was not able to attend the rally. He probably would have been the only issei from Toronto to participate.”25 According to Mizuyabu, Mr. Kitamura always had the courage to follow his own convictions even if it meant defying those in power. It was a matter of principle for him. He would never permit anyone to stifle his voice or convince him that he did not have a right to individual compensation. Yuki Mizuyabu states that Mr. Kitamura was one of the few issei who refused to voluntarily leave the POW camp after the war ended. He said that he would not leave unless he could return to his home on the Pacific coast. He stuck adamantly to his belief that the government should have returned him and his family to the location from which they had been uprooted. In fact, the legal points which Mr. Kitamura raised at the time have since been supported by Canada and the United Nations in various cases around the world where ethnic minority groups have been returned to their homes after expulsion by a discriminatory government.26

NAJC Toronto Chapter president, Bill Kobayashi, was very proud of what had been accomplished in only four months. In assessing the long range impact of the Ottawa Rally, he stated: “The rally was successful beyond all expectations. Gratitude is due to the volunteers and participants who made many sacrifices to attend. Not to be forgotten are the many who were unable to attend but gave generously to finance the program and the ‘Ribbons of Hope’. The Redress movement, whatever its outcome, will be remembered for its spirit of community in its fight for justice.”27

The Ottawa Rally brought together Japanese Canadians of all ages, all parts of the country, with support from all quarters, in particular from non-Japanese Canadians. It stands as one of the proudest and brightest moments of the Redress campaign.

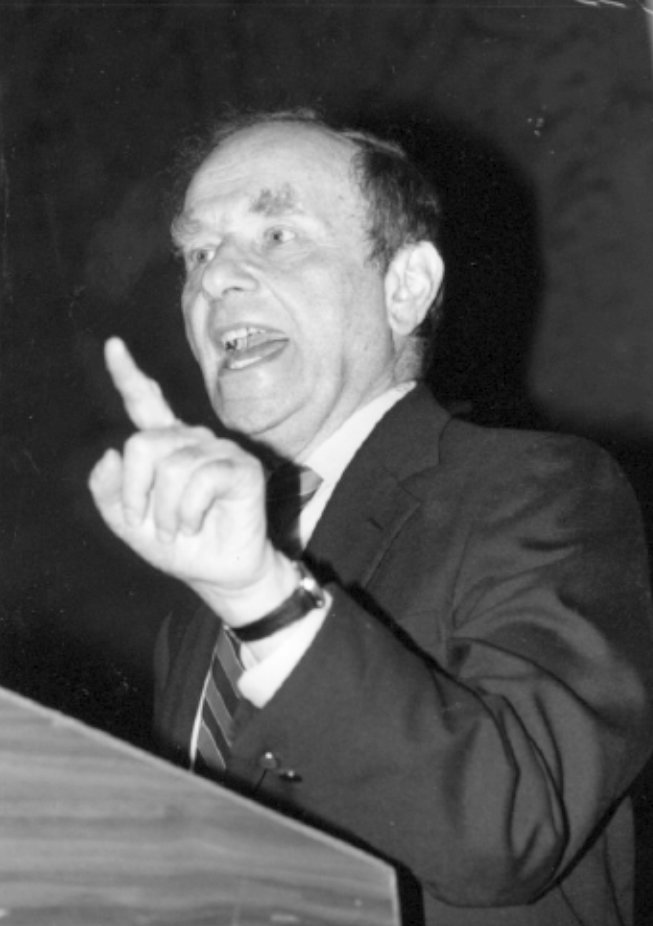

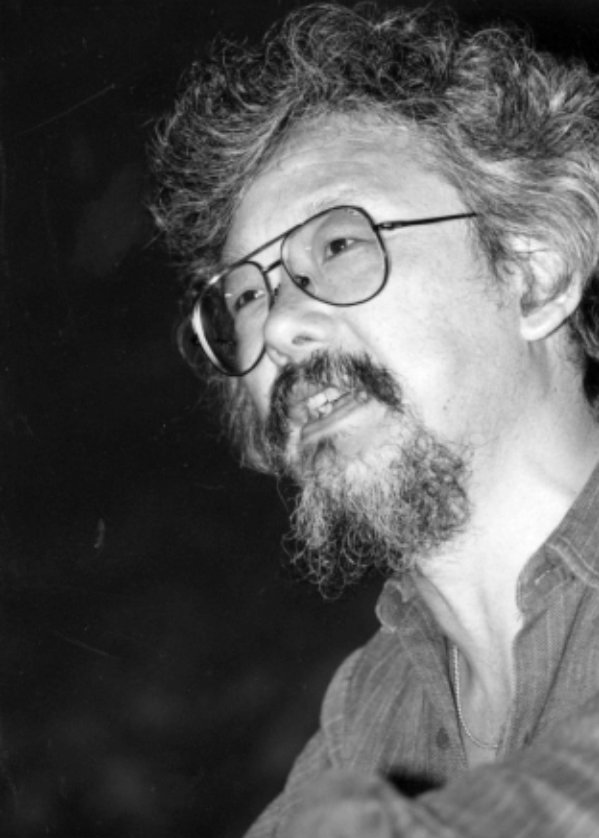

DAVID MOTOSUNE MURATA was born in Shizuoka-ken, Japan in 1957, the son of Rev. Ben Murata, who was minister of the Japanese congregation of Centennial United Church in Toronto. He came to Canada when he was eleven years old. After graduating from the University of Toronto and the University of Western Ontario, David was a lecturer in ethics at U of T. He served as a United Church minister in Vancouver for many years until he became a senior partner in a consulting firm. In late 1987, he got actively involved in the Redress movement in Toronto when the NAJC appointed him National Redress Coordinator and Chairman of the Ottawa Rally Steering Committee, headquartered in Toronto. (Photo courtesy Blanche Hyodo)

KEN NOMA has taught high school for the Toronto District School Board for over 25 years, yet he has found time not only to volunteer in the Japanese Canadian community, but also to work on educational projects designed to enhance intercultural understanding. From 1990 to 1995, he established Pacific Rim credit courses at the high school level and active student and teacher exchanges between Canada and Japan. During the Redress years he worked closely with Sodan Kai members to design and lead high school workshops on Redress and racism. He also served on the Toronto based committee that organized the Ottawa Rally and as president of the NAJC Toronto Chapter, 1989-90. (Photo courtesy Harry Yonekura)

Hide Shimizu filling mailbags with postcards of support to be delivered to Brian Mulroney by NAJC members, April 14, 1988. Hide, who received the Order of Canada for her work as a teacher in the internment camps, was one of the speakers at the pre-rally banquet of April 13, 1988. She passed away in August 1999. (Photo: Gordon King)

Front and back of postcard of support printed on bright yellow cardboard. A total of 63,000 cards were distributed across Canada. The downtown post office box where the signed postcards were mailed back had to be emptied frequently, usually by Toronto NAJC member Van Hori.

Leading the march to Parliament Hill, from left to right are Charles Kadota from Vancouver, Roger Obata (then NAJC National Council Vice-President), Bill Kobayashi (then President, NAJC Toronto Chapter) and Dave Murakami from Toronto. Also near the front of the line were Mary Obata (seen behind Bill), Mas Kawanami from Calgary and Kiyoshi Shimizu from Victoria. (Photo: John Flanders)

World War II veteran, Roger Obata, raises his placard in preparation for the march. He was at the forefront of Redress activities since the early days of the Bird Commission. (Photo: John Flanders)

Alan Borovoy of the Canadian Civil Liberties Association delivered an impassioned speech at the Ottawa Rally forum. He stressed the significance of viewing the struggle for Japanese Canadian Redress as the struggle for “social justice for everybody”. Many people were in tears when he uttered, “Never again! Never again! This will bloody well never happen again!” (Photo: Gordon King)

David Suzuki, scientist and broadcaster, was one of the main speakers at the indoor forum on April 14, 1988. He spoke eloquently about the effects of the expulsion on him personally as well as the role of our Redress struggle in the larger struggle for human rights. Towards the end of his speech he stated, “We cannot speak of Canada as just a place, a democracy, a country of equality for all, so long as we fail to address native claims and native rights. And so I urge all of you to look on our struggle for justice for the Japanese Canadian community as the beginning of a much greater struggle.” (Photo: Gordon King)

Demonstrators carrying placards and yellow “ribbons of hope”, preparing to enter the Parliament Buildings. These yellow ribbons represented the names of Japanese Canadians who were at the rally in spirit—those who could not attend because or work commitments and illness, along with those who had passed away too soon to witness this memorable event in Japanese Canadian history. Recognized in this photo are Matthew Okuno, Wes Fujiwara and Joanne Sugiyama (holding sign).

Demonstrators pour into the West Block entrance of Parliament Buildings on the morning of April 14, 1988. (Photos: John Flanders)

ADDIE KOBAYASHI is a nisei who was born in Vancouver. Addie and her family were interned in Tashme and moved to Montreal in 1943. In 1954, Addie married Bill Kobayashi and they raised six children. Addie has worked for the National Film Board as a secretary and a freelance transcriptionist and for Brock University in St. Catharines as a secretary. Her deep interest in the Redress movement began during the JC Centennial and since then she has contributed to her community in countless ways as a member of the NAJC Toronto Chapter. In 1987, Addie organized the memorable NAJC 40th Anniversary Celebration. She is also the author of Exiles in Our Own Country: Japanese Canadians in Niagara. (Photo: John Flanders)

John Turner, then Leader of the Opposition, chats with World War II veteran and past JCCA/NAJC President Harold Hirose at Ottawa Rally. (Photo: courtesy Jennifer Hashimoto)

Notes

1 “April Public Forum Planned Buses Converge on Ottawa”, Nikkei Voice, Vol. 2, No. 1 (February 1988), p. 1.

2 Letter from Roger Obata to NAJC National Council members, dated July 25, 1985.

3 Group taping session of the Ottawa Rally, May 3, 1993.

4 Ottawa Rally tape, May 3, 1993.

5 Quebec NAJC bulletin.

6 Group taping session on the Ottawa Rally, May 3, 1993. Jennifer Hashimoto created the forms for the Ribbon of Hope donations.

7 Ottawa Rally group taping session., May 3, 1993.

8 Bill Kobayashi, taped recollections, April 13, 1988 bus trip to Ottawa Rally, 25-40.

9 Roy Sato, taped recollections, April 13, 1988 bus trip to Ottawa Rally, 50-65.

10 Hide Shimizu was the first JC public school teacher in British Columbia. She trained teachers in the internment camps and became a Member of the Order of Canada for her wartime efforts to continue the education of JC children. Sadly, Hide passed away in August 1999.

11 The MC for the pre-rally banquet was NOT Paul Kariya the famous NHL hockey player, but a cousin of his.

12 Yuki Mizuyabu’s Ottawa Rally notes provided for May 3, 1993 taping.

13 Group taping session on the Ottawa Rally, May 3, 1993.

14 Ibid.

15 Interview by Jennifer Hashimoto with Blanche Hyodo, November 29, 1994.

16 Chiba, Charlotte. “Ottawa Rally, April ’88—A Retrospective", JC Community News Special Edition: The Ottawa Rally. April, 1988.

17 Miki, Art . [speech]. April 14, 1988, National Redress Forum, Ottawa.

18 Archbishop Ted Scott. [speech]. Ibid.

19 Borovoy, Alan. [speech]. April 14, 1988, Ottawa.

20 Suzuki, David [speech]. April 14, 1988, National Redress Forum, Ottawa.

21 Roger Obata, notes, August 5, 1995.

22 Roy Miki speech, April 14, 1988, National Redress Forum, Ottawa.

23 Ottawa Rally group taping session, May 3, 1993.

24 Ottawa Rally group taping session, May 3, 1993.

25 Yuki Mizuyabu’s Ottawa Rally notes for May 3, 1993 taping session.

26 Yuki Mizuyabu, unpublished article on issei participation in Redress movement, July 1999.

27 Bill Kobayashi, JC Community News Special Edition: The Ottawa Rally, April 1988.