Chapter 6

Community Conflict

By the Ad Hoc Committee, Japanese Canadian Redress: The Toronto Story

Based on the notes of Roy Ito and the Committee

Those who would lead the Redress negotiations could not afford any internal conflict in a community of only 15,000 people, yet the conflict was there and inescapable. It might never have developed if all the individuals involved had abided by the democratic principle of majority rules.

Before one can begin to understand the conflict that emerged in our community, it is necessary to look at the evolution of the various Japanese Canadian organizations that played a role in the Redress drama of the 1980s. In Toronto, the NAJC chapter was known as the Greater Toronto Chapter of the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA). The NJCCA and the NAJC were one and the same organization, the NJCCA having changed its name to NAJC in 1980 in order to be inclusive of other Japanese Canadian organizations. The NAJC was being recognized as the only organization with the credentials to represent all JC communities across Canada.

As the chapter representing Toronto at NAJC national council meetings, the Toronto JCCA held five votes, due to the immense size of Toronto’s Japanese Canadian community compared to most other JC communities. A formula was designed to avoid domination by Toronto and Vancouver, the other equally large JC community. Nevertheless, the Toronto JCCA president, who controlled the five votes, had a lot of influence over the decisions of the parent body.

The Toronto chapter’s president was then Ritsuko Inouye. She and her fellow directors had all been elected at the Annual General Meeting of 1980. There were no more general meetings until 1986. We will never know for certain why no annual general meetings were held between 1983 and 1985. If it was because of a lack of interest in the Toronto JCCA, then Redress presented the executive with an excellent opportunity to get the JC community involved and, at the same time, to renew their mandate to represent both the community and the chapter.1 Redress was an issue that could bring out hundreds of JCs, but the inaction of certain members of the Toronto JCCA executive made me wonder if they really wanted to hear how the majority felt about Redress.

The behaviour of the Toronto JCCA executive during the 1980s was quite different from that of their Vancouver counterparts. The JCs of Vancouver held regular democratic elections—and therefore they did not have to waste valuable time and energy on internal conflicts. They could give the Redress campaign their full attention. But in Toronto, we faced very serious problems. Toronto JCCA directors appeared to be locked into their positions of power. If they had been allowed to continue unquestioned in this undemocratic fashion, the entire Redress outcome would have taken a different direction.

A $50 Million Proposal Out of the Blue

The first major indication of an attempt to bypass the democratic process was in early 1983 when George Imai, as chairman of the National Redress Committee (NRC), announced a proposal to obtain a $50 million community fund from the federal government. This announcement came out of the blue, hitting many Japanese Canadians across Canada like a bolt of lightning. It seemed as if Imai had not conferred at all with Gordon Kadota about this move. Kadota, then the national president of the NAJC, was still weighing the options in order to develop a national consensus on Redress. Despite the fact that he was chairman of the National Redress Committee, George Imai had no authority to present any proposal to the federal government without prior approval from the entire NAJC National Council, which is comprised of representatives from major JC centres across Canada.

The National Redress Committee, established by the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) at the Annual General Meeting in 1980, was merely supposed to research and study the subject of Redress and make recommendations to the parent body, the NAJC. Its initial chair was Naomi Tsuji, but shortly after her appointment, ill health forced her to resign, and George Imai took over. But instead of acting as a subcommittee of the NAJC, the NRC, under the leadership of George Imai, was run like an independent organization, going far beyond its mandate. Imai claimed to be acting on behalf of all Japanese Canadians, and particularly on behalf of the issei. But there were several members of the Japanese community who questioned his motives and his methods.

As a member of Toronto’s JC community, I became involved in the Redress movement because I was so incensed by the arbitrary actions of George Imai, but like many others in our community, I did not know what I could do about it. Then one Saturday morning in May 1983, I happened to see a flyer at the Toronto Japanese Language School (TJLS) about a public information meeting sponsored by an organization called “Sodan Kai”, a name that seemed odd to me since I associated these words with a group “discussion” or “consultation", not an “organization1”. I was suspicious at first because I thought it might be a trick to get those attending the meeting to approve some pre-determined Redress position. Nevertheless, my friend, Takaaki Kitamura, and I decided to go hear what was going on.

We were pleasantly surprised to discover that the meeting was held strictly for the purpose of informing and educating the community on the different Redress options that were being pursued in the United States by two Japanese American groups—one trying to reach a political settlement through legislation and another trying to sue the government for damages. In addition to the American speakers, we heard from George Imai, as NRC chairman, and his superior, NAJC president Gordon Kadota.

As I recall that meeting, there was a lack of coordination between these two men. While Imai essentially repeated what he had already said to the press about a $50 million community fund, Kadota said that he was still visiting the various JC centres in an effort to reach a consensus on what sort of Redress the JC community wanted to pursue. Publicly, at least, they should have been in agreement, but they were obviously on two different planes. This meeting was a clear indication to me of a deepening conflict that was fuelled by just two or three individuals.

Imai appeared to be working in a vacuum. His group was still using the old name of Toronto JCCA long after the name had been changed nationally to the NAJC. And the executive failed to hold public meetings to get the input of the thousands of nisei and issei living in the Toronto area, let alone in the rest of Canada. Understandably, many Toronto area JCs felt that they could no longer have faith in him as a spokesperson for our community. Some members of the community felt that it was time to curb his power before things got out of hand.

At a meeting in Toronto on Thanksgiving weekend, October 1983, the NAJC established a reporting mechanism that would strengthen the NAJC’s control of Imai’s National Redress Committee. Imai opposed this attempt to restrict his power. He stomped out of the meeting, announcing his resignation. In stereotypically Japanese fashion, instead of saying, “thanks for your past service and good-bye", a delegation was sent to try to coax Imai back into the fold—and he came back.

Nikko Gardens, November 1 and November 29, 1983

Those of us in favour of seeking individual compensation, together with the sansei dominated Sodan Kai, held a number of meetings that shook the community, but ultimately made us a stronger and more democratic community. Many of the “Redress” meetings that were held between November, 1983 and June, 1984 took place at an old landmark on our Toronto Japanese community map: Nikko Gardens in the heart of downtown Chinatown.

Today Japanese restaurants are commonplace, but back in 1983, there were just a handful of them. Nikko Gardens was probably the first one in Toronto. It was situated on the second floor of 460 Dundas Street West, just east of Spadina and upstairs of the former Furuya Trading Company. Competition forced it out of business in the mid 1980s, but for several decades it provided a comfortable and familiar meeting place for many nisei and sansei in Toronto. A few years before Nikko Gardens closed its doors, it became the site of some important debates in our community—debates that reopened old wounds and stirred up new conflicts.

Before the official Redress meeting of November 29, 1983, about 50 of the Issei-bu (the issei section of the JCCA) met at Nikko Gardens on November 1, 1983 for a meeting chaired by Sumie Watanabe. Four motions were introduced: to seek a formal apology, to support the position to seek group compensation, to support the Toronto JCCA and to support the National Redress Committee of the NAJC in the matter of Redress. All four motions were passed without a formal vote. George Imai, chairman of the National Redress Committee, concluded that whatever the issei advocated was of utmost significance, since they were the ones who had suffered most. “Issei no kata tachi no tame ni” (for the sake of the issei). This phrase created the false impression that the majority of issei across Canada were behind him.

Later the community newspapers reported the meeting from George Imai’s point of view. But somehow what I read did not match my recollections. How the four motions were considered to have been approved was a mystery to me for I had not witnessed any formal voting procedure—no counting of hands or slips of paper. My presence at this “issei” meeting was on behalf of my father who was too ill to attend. Surprisingly, I had been granted permission to speak. Aside from me and the nisei conducting the meeting, almost no one else uttered a sound. This was typical, I suppose, for a gathering of issei not used to expressing their opinions publicly or opposing authority. I suspect that Imai interpreted their silence as tacit approval of his proposals.

When it was my turn to speak, I pointed out various holes in Imai’s arguments, stressing the fact that I knew of many issei who were actually strongly in favour of individual compensation. I said that those who opposed it had not been given sufficient information. Instead they had been fed the message that the group compensation package alone was the more unselfish, community-spirited option. The implication was that any other position would be shamefully greedy and selfish.

Speaking in Japanese, I was pretty fired up. I emphasized that what we were seeking was nothing more than what we were morally and legally entitled to. Looking around the room, I could see that the JCCA Issei-bu did not have enough active members to adequately represent all the surviving issei in Canada. My father was not a member, nor were any of his close relatives, but here was George Imai speaking on their behalf. Given this situation, we were very fortunate to have the Sodan Kai emerge on the scene when it did for its members brought a refreshingly unbiased approach to the Redress issue, encouraging input from all sources including those inside and outside the JCCA.

Following the “issei” meeting, we held our “Redress” meeting on November 29, 1983. Under pressure from the Sodan Kai, the Toronto JCCA agreed to co-sponsor a meeting with them to discuss the formal structure of our newly formed Toronto area committee on Redress. A notice had appeared in community newspapers and churches a few weeks earlier inviting JC organizations to send representatives or alternates to Nikko Gardens on November 29.

I attended the meeting as a private individual. I informed Ritsuko Inouye, president of the Toronto JCCA and the chairperson of the meeting, of my status because she knew me from the Toronto Japanese Language School (TJLS), where I had been an active volunteer for many years. I did not want her to assume that I was at the meeting on behalf of the TJLS. I made it clear that I was only representing myself.2

The first problem facing the new Toronto Redress group was finding an official name for the committee. It was a tossup between “Toronto JCCA Redress Committee” and “Toronto Redress Committee". After a lengthy discussion, Henry Ide reminded everyone that the original intent was to have the committee under the umbrella of the Toronto JCCA. A motion, moved by Dennis Madokoro and seconded by me, to adopt the name “Toronto Redress Committee” was defeated by a margin of 40 to 18. Finally, we settled on George Imai’s choice, “Toronto JCCA Redress Committee” since most of the participants present assumed the attitude, “What’s in a name?” I was skeptical about including the name “JCCA” in our new committee because it would make it subordinate to the Toronto JCCA, an organization that did not represent the majority of Japanese Canadians in Toronto.

We soon discovered that the whole thing was a bit of a farce, a mere semblance of democracy. It didn’t matter what the name was because the resulting slate of nominees for the committee was still dominated by the old Toronto JCCA executive, with token representatives from various community organizations. Without any advance notice or consultation, a slate of about 18 names was presented. Although it included Maryka Omatsu, Marcia Matsui, Ron Shimizu and Harry Yonekura, most of the other names were of those who were generally opposed to individual compensation, people such as Jack Oki and Sumie Watanabe.3

I suggested that at least one person be added to the committee from every organization that sent a representative to the meeting. The JCCA executive criticized my proposal, claiming that such a committee would be too large and unwieldy, but when Rev. Roland Kawano (of the Japanese Anglican Church) supported me, my suggestion became a motion and was passed. Thus, new blood was added to the committee, representing such diverse groups as the JC Tennis Club (Dennis Madokoro) and the Hiroshima-ken jin kai (Ken Kambara).4

The enlarged committee was then approved. However, since the committee members from the participating organizations were only additions to the original slate proposed by the JCCA executive, the Toronto JCCA leaders still managed to retain their control by being able to out-vote any opposition to their proposals.

Establishing Toronto JCCA Redress Committee, December 14, 1983 and January 11, 1984

At another meeting at Nikko Gardens on December 14, 1983, we held formal elections and confirmed the membership of the newly formed Toronto JCCA Redress Committee. Jack Oki was elected chairman and Frank Hayashi, Kunio Hidaka and Ritsuko Inouye were elected vice chairmen. Other executive committee members included: Maryka Omatsu and Taye Miyamoto, secretaries; Janet Sakauye and Tami Nishimura, recording secretaries; Marcia Matsui, treasurer; Mikio Nakamura, fund raising; Frank Moritsugu and Koichiro Okihiro, public relations and Art Kobayashi, translator. Nominated and acclaimed as members at large on the executive committee were Henry Ide, Dennis Madokoro and Harry Yonekura.

Following the elections, the door was left open for any other interested individuals to come forward to become involved in the new committee. This motion to invite representatives from other organizations was carried by the majority and aimed at getting the participation of individuals with no previous affiliation with the Redress issue.

Despite the increasingly democratic structure of the new Toronto JCCA Redress Committee, the old guard still dominated the decision making process. There had been a unanimous agreement at the December 14 meeting that “the Executive Committee and the Political Action Sub-Committee should meet to discuss national representation and association and political action, then report back to the committee.”5 Thus, no one had given Imai or Oki the right to make any decisions without consulting the other members.

…It is interesting to note that George Imai seemed to be in a hurry to get the whole Redress matter cleared up quickly. According to the minutes of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee meeting of January 11, 1984, he “emphasized the urgency in starting negotiations on an apology…Monetary compensation negotiations are already too late…”6

In reading over the minutes of that January 1984 meeting, I discovered that no progress had been made in drafting a constitution for the new Toronto JCCA Redress Committee, despite the fact that a subcommittee had been formed with that express purpose. According to Ritsuko Inouye, the chairperson of the constitution subcommittee, it was decided that a new constitution was not necessary. She said that “…being a Toronto JCCA committee, the constitution of the Toronto JCCA7 will be the constitution of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee…”7

This evasiveness was also evidenced in Inouye’s failure to call a meeting to decide which delegates would represent the Toronto JCs at the February 1984 national council meeting of the NAJC in Calgary. In a letter, dated January 14, 1984, to NAJC president, Art Miki, Wes Fujiwara stated that he had sent a letter to Rits Inouye two weeks earlier asking for a meeting, but he had not heard back from her: “It is essential that she does not control all five votes when she is supported by such a small percentage of the population of Toronto…We are therefore taking this opportunity to apply for membership as part of the Toronto delegation or as a separate membership on the council. It is purely semantics but if necessary we can call ourselves the North York centre with a total JC population of about 5,000 if you wish. We are too large and too diverse to be represented by Rits Inouye and her executive alone….At present we are calling ourselves the ‘Toronto Chapter’ of the NAJC, in contra-distinction to…‘The National Redress Committee of Survivors’.”8

Silencing Any Other Redress Groups, March 28, 1984

Another important meeting of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee took place on March 28, 1984 at Nikko Gardens. There was an overwhelming response to our further public call for representatives. The new Toronto JCCA Redress Committee consisted of 60 members. Along with those who had been elected at the December 1983 meeting, were representatives from the various ken jin kai (i.e. community organization based on one’s family prefecture of origin in Japan), the Garden Club, Toronto Buddhist Church, Konko Church, Japanese Anglican Church, Centennial United Church congregations, Wynford Seniors, Judo Canada, Kasaaragi Club, Momiji Health Care Society, the Kotobuki kai and the Gakuyu kai.9

The March 28, 1984 meeting resulted in the passing of a “Community Agreement” stating: “The Canadians of Japanese ancestry in Toronto have given the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee the mandate to act on their behalf on Redress matters” and that “…all activities including recommendations concerning redress arising from Metro Toronto should be discussed and channelled through the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee.”10

Unfortunately, this agreement was easily misinterpreted.In the spring of 1984, a public statement was issued claiming that the new Toronto JCCA Redress Committee would be the official and only voice on Redress matters. According to this statement, Canadians of Japanese ancestry in Toronto had given the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee the mandate to act on their behalf and all other Redress advocacy groups in Toronto—including the Sodan Kai—were ordered to cease existence immediately. The dictatorial tone of this announcement was an indication of the inherent discord that plagued the newly formed committee.

In some respects, the Sodan Kai had taken on the role of legal watchdog for they were frequently uncovering examples of bias on the part of The New Canadian and The Canada Times—two Toronto based community newspapers whose owners made no attempt to hide the fact that they were supporters of the community fund compensation-only proposal. The newspapers lacked the resources and necessary personnel to report objectively on complex matters such as Redress so the articles usually consisted of letters to the editor written by George Imai supporters. Thus, I felt that it was futile to write to these papers because our letters were rarely published. Since Sodan Kai openly criticized this biased journalism, it was no wonder that the Toronto Redress Committee chairman was anxious to silence this outspoken group.

The Sodan Kai members who sat on the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee realized that the committee membership was stacked in favour of the Toronto JCCA and they did not hesitate to raise their voices about the unfairness of the committee composition. Thus, the various Redress Committee meetings often ended in shouting matches. The Sodan Kai members accused Jack Oki of being incompetent and incapable of following the accepted Rules of Order for conducting a meeting. They complained that he limited debate on matters that he disagreed with. He was accused of refusing to call executive meetings or public meetings when requested to do so. The Sodan Kai also claimed that he ignored suggested changes in the agenda. Perhaps the most unforgivable act on the part of some members of the Toronto JCCA executive was planting the fear of a “backlash” in the minds of the issei. Faced with such unprofessional behaviour and internal conflict, it was not surprising that an irreparable split was imminent.

A Petition and a $5 Million Surprise

By the middle of April 1984, several new developments had taken place. At the NAJC National Council meeting, Tony Nabata of Ottawa proposed that the NAJC seek $500 million in individual compensation. The proposal was not approved. Around the same time, BroadviewGreenwood MP Lynn MacDonald tabled a private member’s resolution in the House of Commons in support of our case for compensation and a re-examination of the War Measures Act.11

The JC community was also buzzing about a petition, with over 300 names, that Wes Fujiwara presented at the April 7 conference, along with his grievance regarding the internal problems within the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee. The petition stated: “We, the undersigned Japanese Canadians living in Toronto and vicinity, believe that the Toronto JCCA and the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee did not fully represent the diversity of opinions on redress in our community at the national conference in Winnipeg. We therefore present the following position and ask the Council of the National Association of Japanese Canadians to consider this course of action…” The action recommended was that any negotiations with the federal government be accompanied by a well-documented and comprehensive brief regarding losses suffered during and after World War II. It also stipulated that any compensation be based on the research findings and that the JC community be kept fully informed about this research and the progress of negotitions.12 It is important to note here that the Economic Losses Survey conducted by Price Waterhouse in 1986 was originally recommended by NAJC supporters in Toronto through Wes Fujiwara’s petition of April 7, 1984 in Vancouver.

Wes Fujiwara’s attempts to expose the problems within the Toronto JC Redress movement sparked a personal attack against him in The Canada Times. The article never mentioned him by name, but referred to him as “the doctor” and “this member of the medical profession”.13 The same article accused the Sodan Kai of using underhanded, illegal methods to obtain signatures for the petition.

By this stage in the Redress saga, Art Miki was fully entrenched as the new NAJC president, having succeeded Gordon Kadota. But, unfortunately, there was little improvement in the relationship between the National Redress Committee (NRC) chairman and the NAJC president. As president of our national organization, Miki was actually ex officio member of the NRC. However, when the NRC held its first meeting after his election, he was not even notified and would have missed the meeting if someone had not informed him at the last minute.

The meeting was held at a new venue, the Oakum House of Ryerson University. Among the issues discussed at the Ryerson meeting was the one concerning the NRC’s alleged usurpation of the parent body’s role. As chairman of the NRC, George Imai had applied directly for a $100,000 dollar grant from the federal government and had already received $60,000 of it. Art Miki was outraged by Imai’s actions. He argued that it was totally improper for any committee of the NAJC to be directly approaching the government for funds without the consent of the parent body. The remaining balance of the grant would have to go the NAJC head office, insisted Art Miki. Reluctantly, Imai’s committee agreed to comply.

In spite of the NRC’s insubordination, it appeared that the NAJC National Council was still not prepared to do anything drastic about it, as long as the insubordination or lack of cooperation did not do significant damage to the Redress movement. But, in June 1984, just a short time after Miki’s visit, Mas Kawanami, the NAJC Council member for Calgary and a World War II veteran, was invited by George Imai to attend a special event in Ottawa, along with other selected Japanese Canadians from across Canada. Through our information network, we learned that David Collenette, then the minister of multiculturalism, planned to announce that a $5 million dollar fund to promote racial harmony was being established to settle the JC Redress issue.

Here in Toronto, we reacted to this news like bees trying to defend their hive from a bear. It was incomprehensible. How could the government possibly expect us to settle for such a paltry amount—an amount that was more like koden, condolence money, for a premature death? Pro-NAJC activists got busier than ever alerting the community about this impending travesty of justice. Joy Kogawa promptly arranged for the use of the Church of the Holy Trinity in downtown Toronto, just behind the Eaton Centre, for a mass protest rally.

We were incensed. Some of us even called George Imai’s house to ask him to come out and explain his clandestine actions. No one answered the phone. On June 17, 1984, within days of our protest rally at Holy Trinity, Miki called a teleconference of the NAJC council members to deal with the crisis that the NRC chair had knowingly or unknowingly created—a crisis that almost resulted in the premature death of our dream of Redress. Miki immediately called for a motion to dissolve the National Redress Committee. George Imai’s gathering of Japanese Canadians in Ottawa to witness Collenette’s proposal was certainly ample justification for dissolving the wayward NRC.

June 1984 Protest at Holy Trinity

We spent many gruelling hours on the phone in our efforts to inform as many people as possible within a short time about the emergency protest rally. Our efforts proved to be worthwhile as the Church of the Holy Trinity, the venue for our public gathering, was filled to capacity. Speaker after speaker denounced the Collenette plan and George Imai’s apparent complicity. Those present at the rally wholeheartedly approved of sending a telegram of protest, not only to Collenette and the Prime Minister, but also to leaders of the opposition parties and other ministers. Our telegram bluntly stated that the Collenette plan was totally unacceptable and that it would trivialize the injustices suffered by the Japanese Canadian community.

We ended our message with the fact that Art Miki, our NAJC president, was the only person accredited to represent our community in Redress negotiations with the government. This telegram was signed by some prominent members of the community, names that Ottawa politicians could not ignore: Tom Shoyama (who rose to one of the highest positions in the federal civil service), David Suzuki (environmentalist and geneticist), Joy Kogawa and Ken Adachi (both well known authors), Roger Obata (founding president of the National JCCA), and Stan Hiraki (former president of the Toronto JCCA). Surely, the impact of these names and the call from Art Miki would bring an abrupt halt to the proposed plan.

The atmosphere in and around Holy Trinity that day was charged with emotion, most of it directed against George Imai. As I sat there listening to the angry speakers, I felt a little uneasy because I was with George Yamazaki and Tony Tatebe, two other ex-internees of the wartime Lemon Creek camp. Tony happened to be an in-law of Imai’s. I couldn’t help wondering how Tatebe was feeling about all the negative comments being hurled against his relative.

David Collenette got the message loudly and clearly. He had no choice but to cancel his announcement and begin treading more carefully and straightforwardly in matters concerning the Japanese Canadian community. If Collenette and Imai had succeeded in having a substantial Japanese Canadian presence at their press conference, it would have been interpreted by the public as a JC endorsement of their deal. The Liberal government could then say that it had finally settled the Redress issue once and for all, closing the door to any further negotiations. When an outraged Art Miki contacted Collenette’s office, one of his aides seemed puzzled by the fact that Miki, as president, had not known about the deal since someone “representing the NAJC” had been in frequent contact with Collenette’s office as the plan developed. There was no doubt in the minds of many people that George Imai was that someone.

When we finally tracked him down, Imai would not admit that he had done anything improper. He was given a chance to defend himself and denied having been in “frequent contact” with Collenette’s office, claiming that the Collenette plan was not, in fact, a negotiated Redress settlement, but merely an immediate response to the government commissioned Equality Now report by the Special Committee on Visible Minorities.

Miki was not gullible. He rejected Imai’s implausible interpretation of the Collenette plan, pointing to the fact that the government commissioned report specifically recommended that the government negotiate with the NAJC. There was no mention in Equality Now of the Toronto JCCA or the National Redress Committee. Also, if Collenette’s plan had nothing to do with JC Redress, then he would not have called off his scheduled announcement when he found out that there would be no significant JC presence at his media event.

Later we learned that Imai had only asked certain members from the NAJC Council to go to Ottawa. Aside from Mas Kawanami of Calgary, he had contacted Jerry Hisaoka of Lethbridge, Tim Oikawa of Hamilton and Vic Ogura of Montreal, a long time supporter of George Imai. Ogura also rounded up some issei from Montreal for this trip to Ottawa. Most of these people were given very sketchy information about the reason for going to Ottawa. Each person heard a different vague story.

The NAJC Council, led by Dick Nakamura of Victoria, voted to dissolve the National Redress Committee. But even after its dissolution, the problem of leadership in the Toronto JC community remained up in the air. Allowed to speak at the NAJC Council meeting as a Toronto representative, Roger Obata assured council members that any work previously under the jurisdiction of the National Redress Committee could be adequately handled by two recently-formed committees, the Brief Committee and the Strategy Planning Committee. After lengthy discussion, the motion was carried with 17 “yes” votes, 2 “no” votes and 9 abstentions. George Imai supporter, Ritsuko Inouye, abstained from casting Toronto’s five votes, despite the fact that she openly advocated a continuation of the NRC. At the same time, she refused to allow Obata or any other Toronto representative to cast even part of the Toronto votes. When Miki put the problem of the Toronto votes before the NAJC National Council, no one would take a stand for or against Inouye, insisting that it was strictly a “Toronto problem” that did not concern them.

Dissolving the Wayward NRC in a Teleconference

The Toronto supporters of the NAJC who were informed met at the Obata residence to participate in a national teleconference to dissolve the NRC. Those present included Wes Fujiwara, Van Hori, Bill Kobayashi, Yuki Mizuyabu, Roger and Mary Obata, Hedy and Harry Yonekura, Stan Hiraki, Matt Matsui, Matthew and Polly Okuno and others.

As a result of the NRC’s dissolution, George Imai was stripped of any status within the national organization. Now no Canadian politician could ever pretend to be dealing with a spokesperson for the Japanese Canadian community by talking to Imai. Because he and his supporters were primarily from the Toronto area, the press and the JC communities outside Toronto were under the distorted impression that the Toronto JC community was somehow of the same mind as Imai. Finally, we could begin to rebuild our public image and counteract this false impression by convincing our fellow Japanese Canadians that the majority of Toronto JCs supported the efforts of Art Miki and the NAJC rather than any organization headed by George Imai. Speaking to a reporter from The Globe and Mail, Miki stated: “Mr. Imai was quite upset about this. But council members decided it was time to take some drastic steps…. [He] knew the rules of the game. The only solution was for us to dissolve the committee.”14 The National Redress Committee had committed itself to be accountable to the National Council of the NAJC by resolution in the “Report of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee of 1984” (pages 8 and 9). The NRC with George Imai as chair had unilaterally commenced negotiating with David Collenette to resolve the Redress issue by inviting certain individuals to Ottawa to witness this event without informing the national president and the National Council. This was a callous betrayal of the aforementioned resolution.

After the humiliation of being ousted from office by the NAJC National Council, I assumed that George Imai would want to stay out of the limelight and divorce himself from the Redress issue, but I was mistaken. He surprised us all by bouncing back and bringing media attention to his organization called the National Survivors Committee. Soon after the dissolution of the NRC, he made statements to the press announcing that the community was split wide open and that he represented 1,500 survivors (900 in the Toronto area and 600 in the Vancouver area) who opposed the NAJC Redress position. Interestingly, he was now saying that he would “continue negotiating with the government”15, when just a short time before in his meeting with the NAJC Council, he had denied being the person from our community in communication with Collenette’s office.

Imai claimed that he was the spokesperson for the “silent majority”. It was a mystery to me how he could be so sure that he had the support of people who barely said a word at public meetings. The Canada Times reported that the co-chairs of this “Survivors’ Committee” were two issei in their nineties, two people whom I was certain would not have the stamina to sit through a marathon meeting on the Redress issue. I questioned the credibility of this new organization in a letter to the editor of The Canada Times. But I should have known that it would be a waste of time to send a letter since the publisher, Harry Taba, was a close friend of George Imai. My letter was never published.

Walking Out in Disgust on June, 27, 1984

The last straw was on June 27, 1984 at a full and final meeting of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee. In light of the announcement in the press of a “Separatist Redress group” affiliated with George Imai, Wes Fujiwara moved that “the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee reconfirm its support of, and its membership in, the National Association of Japanese Canadians.” Fujiwara further requested “this vote be a recorded vote by Roll Call.”16

George Imai promptly made a motion to table the motion. After a lengthy, heated debate, Imai’s motion was carried, making further discussion on the subject impossible. Then Fujiwara, Stan Hiraki, Matt Matsui, Kunio Hidaka, Roger Obata and Harry Yonekura got up and walked out of the meeting in disgust. Through their abrupt departure, they were signalling the fact that they had had enough. They had already wasted almost a year trying to change the ways of people who acted in the name of the community without consulting the community. Any further effort would be useless.

Fujiwara later accused Oki of being derelict in his duty as chairman when he failed to ask Imai to explain to the committee his statement to the press that he was forming a new “survivors’ organization” across Canada to continue meeting with government officials. Surprisingly, The Canada Times published an article by Fujiwara in which he wrote: “Mr. Oki and Mr. Imai used the age old trick of ‘tabling a motion’ in order to avoid a vote on the motion…Moreover, the Toronto chairman allowed…[Imai] to effectively block a motion declaring the Toronto committee’s support of the National Organization, thereby creating the erroneous impression that a large number of the members of Toronto’s Redress Committee do not want to be united with the rest of the Japanese community in one National Organization.” Fujiwara ended his article with the statement, “Incidentally, I am not a ‘young radical’. I am 65 years of age and was an adult on December 7, 1941.”17 This remark was made to refute public allegations that “young radicals” had “taken over the NAJC”.

It was an emotional turning point for the Japanese Canadians in Toronto who believed in individual compensation, as it was soon followed by the formation of the NAJC, North York Chapter. Since the NAJC constitution recognized only one organization for each centre, the name NAJC, Toronto Chapter could not be used yet because the Toronto JCCA was still officially representing “Toronto”.

A further development occurred in the fall of 1984 when the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee formally acted to disassociate itself from the NAJC. It is interesting to note that when this major decision was taken, several prominent Toronto based, NAJC supporters were in Ottawa. Then in early March 1985, a letter was sent to specific Toronto JCCA Redress Committee members expelling them from the committee for supporting the new NAJC North York Chapter. It didn’t seem to matter to them that the representatives whom they were kicking out were chosen by the various community organizations that had been invited to send delegates to the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee.

Analyzing the “Conflict”

The “conflict” in Toronto need not have reached the level that it did. The media created an image of two equal factions, but in reality there was only a handful of individuals actively promoting the notion of group compensation alone. They were supported by a few fellow JCCA directors and issei members who were led to believe that asking for individual compensation would anger the rest of the Canadian population. In opposition to this group, were a few hundred individuals of various generations who felt that the entire community needed to be consulted before anyone approached the government with a Redress proposal. Suddenly awakened in early 1983 by George Imai’s statement to the press on his Redress deal with the government, this group eventually became supporters of the NAJC and the proposals that led to our final Redress Settlement.

Then there were those fence sitters who wanted individual compensation, but were afraid of appearing greedy. The rest of the JC population in Toronto remained relatively uninvolved. Whatever their reasons for staying silently on the sidelines, I do not fault them. In the beginning, I too did not expect our politicians to agree to spend hundreds of millions for a politically insignificant segment of the voting public, but keeping up the fight for justice was something I knew in my heart that I had to do. Unfortunately, the whole process took a little bit longer because of the unparliamentary behaviour of a few people in our community.

Despite the fact that they agreed to expand the membership of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee, George Imai and his supporters made it clear through their arbitrary actions that they were not really willing to share the major decision making power. At one point, I recall Imai saying that he didn’t want too many people involved because the process “would become messy”. If the political process dragged on too long—if too many opinions had to be taken into consideration—a change in leadership might occur in the JC community.

As I see it, these “community leaders” wanted to remain in charge and accept accolades for being the ones to negotiate a settlement—any settlement. Supposedly, they received their mandates to lead the community in 1980 at an annual general meeting of the Toronto JCCA. But by 1983, their mandates had expired and none of them made any attempt to call an annual general meeting to get their mandates renewed.

The situation that we faced here in Toronto was unique because just a few individuals were making major decisions without the approval of the majority. While creating a semblance of democracy with the huge Toronto JCCA Redress Committee, the George Imai group was running a separate campaign behind closed doors. They failed to give the Japanese Canadians in Toronto an opportunity to hear and question their plans. If democratic procedures had been followed in Toronto’s Japanese community, the famous “rift” might never have occurred.

Examining that whole chaotic period 15 years after the fact, I can see that the relative silence of the issei was manipulated over and over again to prove that group compensation was what they really wanted. However, by eventually submitting applications for individual compensation, the Toronto area issei proved that they were never opposed to the notion of individual compensation. Their silence did not signify an acceptance of George Imai’s position, but merely a general feeling of resignation and futility. Very few issei or nisei believed that individual compensation could become a reality because it would be far too expensive for the government. So why waste any time, effort or money to support an unattainable goal?

The majority of issei supported neither individual compensation nor the community fund package. They were still unable to shake off the “shikata ga nai” (it can’t be helped) attitude. The conflict in our community was within the circles of active, vocal nisei and sansei. Most of us vocal ones supported individual compensation because, even if we failed to achieve our goal, it would be better to make an effort to fight for our beliefs rather than be tempted into accepting an easy solution.

Only a few members of the active/vocal JCs opposed the NAJC’s stand on Redress because they didn’t think the NAJC proposal for individual compensation would ever have a chance of being accepted. Thus they chose to push for group compensation and create a respectable façade, one that presented them to the community as being unselfish and only concerned about the welfare of the collective. And, in the eyes of the Ottawa politicians, they would become heroes for saving the government millions of dollars.

Graciously grasping any offer was better than aggressively pursuing something unattainable. After all, the quickest way to negotiate any deal is to accept whatever the other side wants, which is the least costly settlement. Prior to the Japanese American Redress Settlement, passed just before ours, neither a Liberal government nor a Progressive Conservative government agreed to discuss compensating individuals. The reason was cost. Neither party was willing to spend hundreds of millions for an ethnic minority that represented only 1⁄5 of one per cent of Canada’s population.

It was interesting talking to the issei about the compensation question. I remember one time when Harry Yonekura and I met informally with some issei to ask them why they were against individual compensation. I suggested to them that if individuals were compensated, those advocating community compensation could donate their compensation money to whatever community cause they supported. Grinning slyly, one of the issei men replied that if individuals grasped the money in their hands, they would not let go of it (“nigittara hanasanai”). An issei woman sitting across from him nodded her head in full agreement.

Those opposed to individual compensation also included a few nisei who, in one-to-one conversation, professed to have no desire for material benefits. When I went to a seniors’ home to collect signatures on postcards to be sent to PM Mulroney, I had no trouble getting signatures from the non-Japanese staff. Ironically, however, when I approached a nisei who was visiting his mother, he asked if I was with the group supporting individual compensation. When I replied “yes”, he stiffened and uttered, “You’re greedy.” Then he quickly walked away. I dream of meeting this person one day just so that I can ask him if he has since turned greedy and applied for compensation. If so, I wonder if he has donated it to a charity of his choice.

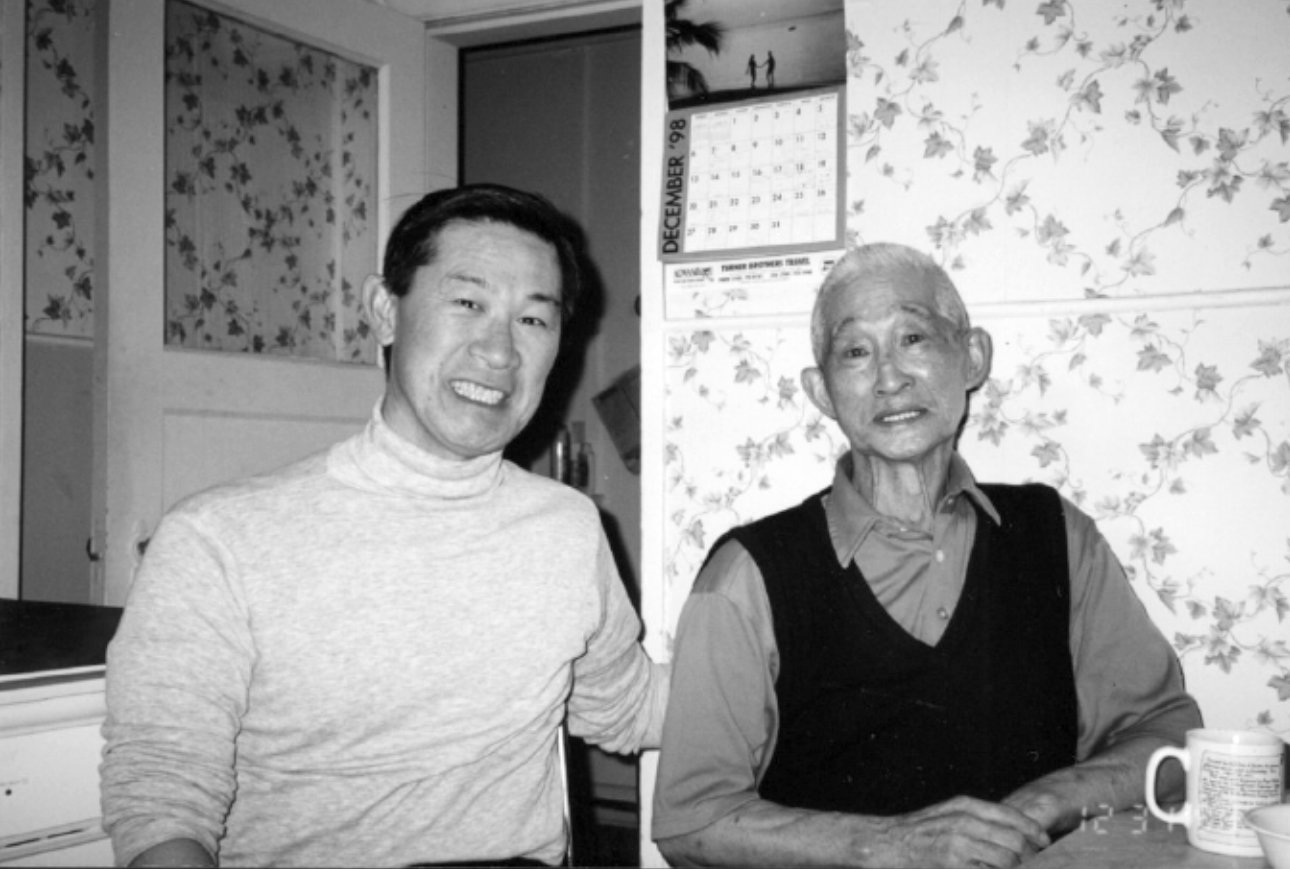

YO MORI (left) was always around helping the NAJC quietly in countless ways throughout the Redress years. He could be seen doing all those jobs that often don’t get noticed—setting up chairs and tables for meetings, hanging up posters, distributing flyers across the city, making telephone calls, putting up decorations for NAJC banquets, dry walling and painting the NAJC office on Harbord Street. As Yo states, Somebody has to do those jobs.”

Yo, a nisei, spent most of the expulsion years in an internment camp in Sandon, B.C. Later he moved to Roseberry, B.C. and eventually to Toronto in 1946. During the 1950s, he served in the Canadian Navy Reserve. He continued his association with the Navy Reserve into the early 1980s as an accomplished saxophonist in the Navy’s band. His involvement in the Redress movement is interesting because he was introduced to the whole issue through his mother, HISA MORI (right), who came from Shigaken, Japan. One night in 1983, Mrs. Mori asked her son to escort her to a meeting at Nikko Gardens Restaurant. Yo recalls, “From that moment on I tagged along with my mother to many more meetings because it was hard for her to get around by herself, especially at night. Since I was there I decided to help out the cause…Compared to most issei, my mother was outspoken. She believed in a fair Redress settlement. She believed in fighting for her rights. She said that she went to those meetings to give George Imai and Jack Oki a piece of her mind.”

Today Yo is retired and lives in Brampton, Ontario with his wife, Jean and their niece, Kimberly. He and Jean have two adult sons, Kenny and Paul who live in Toronto. Recalling his reaction at the Sutton Place Hotel in Toronto when Gerry Weiner made the historic announcement about the Redress settlement, Yo states, “It was a big surprise that we won. It was a joy!” His only regret is that his mother passed away before she could receive her compensation. (Photos courtesy Blanche Hyodo and Yo Mori)

MATT MATSUI (shown above far right with his siblings: Dick, Frank and Mary) was born in October 1914 in Vancouver, the eldest son of a family of five brothers and one sister. Before Pearl Harbor, Matt had a well-established bicycle business in Vancouver and was very active in the Japanese community on Powell Street. After relocating to Toronto during World War II, he again started a bicycle business on College St. near Spadina Ave. and became the neighbourhood’s trusted bicycle doctor. Streams of local politicians, writers and University of Toronto professors wheeled their bikes into his shop. A few doors down was MP Dan Heap’s constituency office where those involved in the Redress struggle could always turn for friendly support and emergency photocopying.

Matt’s customers could read all about developments in the Redress movement because he had newspaper article and flyers all over his doors and windows, information about how the average person could help our cause. He became immersed in the issue through his daughter, Marcia, one of the founders of the Sodan Kai, and his son, Jim. Matt’s friends in the Japanese Canadian community dropped in regularly at his shop to discuss Redress—people like Kunio Hidaka, Yo Mori, Jim Nasu, Rev. Roland Kawano, Yuki Mizuyabu, Joy Kogawa, Ko Ebisuzaki and others. Some of the early strategy meetings of the Concerned Nisei and Sansei took place at Matt’s home. Matt Matsui contributed an enormous amount of time and energy to our struggle. (Photo courtesy Matt Matsui)

DENNIS MADOKORO (left) is a sansei who was born in Toronto in 1945. He is the third child of the late Mary Miki and John Yoshio Madokoro (right), a Pacific fisherman before and after the war for a total of approximately 60 years. In 1951, after a brief period in Toronto, the Madokoro family moved back to B.C. Dennis spent most of his school years in Port Alberni, B.C. After obtaining his B.Sc. from UBC in 1968, Dennis served a short term as an officer in the Canadian Navy. Then he entered the business world in Toronto. He and his wife, Iris, live in Unionville with their two sons, Tim and Clayton.

Dennis began his involvement in the Redress movement in 1983 as a representative on the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee. Later her helped out the NAJC Toronto Chapter in various ways until Redress was achieved in 1988. He got involved because of “a feeling that something had to be done.” He states, “I had heard all the evacuation and internment stories from my parents. The emotions that the stories evoked in me were confusing and disheartening. How could something like this happen in my Canada? Even if we never succeeded, it became, for me, a quest to right a wrong that had happened to my family. In the early 1980s, my father told me that…he would never see Redress happen in his lifetime. I am proud to have been a small part of the process that allowed my father to hear the acknowledgement that the Canadian government had treated him and my mother unjustly.” (Photo courtesy Dennis Madokoro)

SUSAN AND KUNIO HIDAKA, 1973. As noted in Chapter 3, Kunio worked tirelessly for the Redress movement from the early days of the Bird Commission. His wife, Susan, was born in Okanagan Centre in 1929. She spent most of her working years with Imperial Oil Ltd. as an executive secretary. Although she was neither expelled nor interned, she supported the Redress movement because she felt strongly about the injustices and loss of civil rights on the basis of race. Recalling that period, she states, “Job opportunities were limited, travel was restricted and fingerprinting with an I.D. card was mandatory.” Susan Hidaka was on the publicity committee of the NAJC North York Chapter (later to become the Toronto Chapter). Since 1993, she has lived at Momiji Seniors Centre. (Photo courtesy Susan Hidaka)

JACK OKI, a World War II veteran, has served the Japanese Canadian community in Toronto for many years as a member of the Toronto JCCA executive and chairman of the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee. He was also vice-president of the National Council JCCA/NAJC. He is a familiar face at Nipponia Home where he has been longtime chairman of the Board of Directors. Under his leadership, Nipponia Home has undergone extensive renovations. During the tumultuous Redress years he was at the centre of controversy because his views and behaviour sparked angry reactions in many NAJC supporters. (Photo: Roger Obata)

Notes

1 The Constitution of the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association, September 1961, Article VIII, Section 2 states: “The National Executive Committee shall be the elective body of the National JCCA for a term of two years.”

2 Like all other JC organizations, the TJLS had been invited to participate in forming a Toronto Redress committee. As the president of the TJLS Ijikai (or Supporters Association), Mizuyabu called a board meeting to discuss the invitation. The board decided not to get involved in the Redress issue since it was “too political". They would not even agree to send Mizuyabu to the November 29th meeting as an observer. So he went as an individual. But by the spring of 1984, he sat on the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee as an official representative of the Wakayama-kenjinkai

3 Minutes of Toronto JCCA Redress Committee meeting, Tuesday, November 29, 1983.

4 The full Toronto JCCA Redress Committee was comprised of Frank Hayashi, Kunio Hidaka, Henry Ide, Edward Ide, George Imai, Rits Inouye, Ken Kosaka, Marcia Matsui, Martha Matsunaga, Taye Miyamoto, Mikio Nakamura, Denise Nishimura, Tomi Nishimura, Tosh Noma, Jack Oki, Koichiro Okihiro, Maryka Omatsu, Janet Sakamoto, Janet Sakauye, Fumi Sasaki, Ron Shimizu, Mits Sumiya, Kinzie Tanaka, Kizuye Tanaka, George Takahashi, Harry Tonogai, Issaku Uchida, Sumie Watanabe, Harry Yonekura, K. Fukushima, Frank Hatashita, Mr. Ishikawa, C. Ito, Ken Kamabara, Rev. Roland Kawano, Art Kobayashi, Susumu Koyama, Matt Matsui, Mamoru Nishi, Mary Obata, Rosie Ogaki, Shin Omotani, Yoichi Saegusa, H.M. Shimoda, Dr. Fred Sunahara, ShigeoYajima, Yonekazu Yoshida, Sam Murakami, Takeo Nakano, Dennis Madokoro, Frank Moritsugu and George Nishidera. By January 1984, Roger Obata and Stan Hiraki were also appointed to the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee.

5 Minutes of Toronto JCCA Redress Committee Meeting, December 14, 1983.

6 Minutes of Toronto JCCA Redress Committee Meeting, January 11, 1984.

7 Ibid.

8 Letter to NAJC President Art Miki from Wes Fujiwara, dated January 14, 1984.

9 The Gakuyu kai was represented by nisei Matt Matsui. He got involved in the Redress movement when his two children Marcia and Jim, challenged him: “What’s the matter with you? You’d better show up!” Matt decided to go as the representative of Gakuyu kai, an organization composed of graduates and former students of the Alexander Street Japanese School in Vancouver.

10 Minutes of Toronto JCCA Redress Committee Meeting, March 28, 1984.

11 New Democratic Party of Canada news release, April 12, 1984.

12 Petition presented to the NAJC National Council by Wes Fujiwara at April 7, 1984 conference in Vancouver.

13 “Broken Promise", The Canada Times, Vol. No. 35, E-40, May 18, 1984.

14 Hickl-Szabo, Regina. “Japanese Committee on Redress Dissolved", Globe and Mail,

15 McAndrew, Brian. “Split Leaves 2 Groups Claiming to Speak for Interned Japa

16 Minutes of Toronto JCCA Redress Committee Meeting, June 27, 1984.

17 M. Wesley Fujiwara, “Toronto JCCA Redress Committee Splits", The Canada Times, June 3, 1984.