Chapter 3

Relocation to Toronto

By Roger Obata

Before the outbreak of World War II, there were very few nisei in Toronto. Most of the Japanese in Toronto during the 1930s were entrepreneurs from Japan such as Mr. Ubukata who owned Silks Limited, a textile business. There were also some smaller importing businesses operated by Japanese businessmen. Our “community” in Toronto numbered a mere 20 to 30 people. Ubukata, Hirabayashi, Hirai, Harima, Kawakita, Mawatari, Kurata, Oda, Yanagawa and Nishikawa are some of the names that I remember from those early days. Alongside these issei, were a handful of young, ambitious and adventurous nisei from B.C. who decided to try to build careers in Toronto, individuals such as Lily Ide, George Yoshy, Wes Fujiwara, Lily Washimoto—and me.

After graduating from the University of British Columbia in 1937, I ventured eastward to Toronto with my engineering degree proudly in my hands. Since my job prospects in B.C. were non-existent at that time because of racist restrictions in professional fields like engineering and medicine, coming to Toronto seemed like a logical step. Also, in Vancouver I had publicly advocated the idea of spreading the Japanese community across Canada rather than concentrating ourselves in British Columbia. It was time for me to practise what I preached. When I arrived, my hopes were dashed when I discovered University of Toronto graduates delivering milk and bread on horse-drawn wagons. What would my chances be as a Japanese Canadian looking for a decent job? During my first year in Toronto, I could only find work as a houseboy for wealthy families. But by December 1941, through unswerving determination, I managed to secure a position at Philco Radio Company and my engineering career was launched.

Prior to 1942, the nisei and issei in Toronto were a tiny coterie, but by the spring of 1942, several more had found their way to Toronto as the government’s relocation plan was underway. Because the City of Toronto had an official policy banning anyone of Japanese ancestry who came from British Columbia, the initial destinations for many of the relocees were the sugar beet farms in southern Ontario. Mitchell Hepburn, the premier of Ontario at the time, had personally placed an order for 25 relocees for his farm to fill a severe labour shortage. This group included Luke Tanabe, Tats Harada, Harry Naganobu, Dan Washimoto and Tosh Sugiman—along with the Adachi, Kishimoto, Moritsugu and Yatabe families. Other early arrivals were sent to the tobacco farms of the Tillsonburg region. People like Matt Matsui, Johnny Tanaka, Ted Hayashi, Oscar Hatashita, Paul Asada and George Obokata toiled arduously under very difficult conditions. After their mandatory stints on these farms, most of the relocees trickled into Toronto or Hamilton, despite the official ban.

Networking Inconspicuously

It soon became apparent to those of us who had established ourselves in Toronto several years earlier that these new arrivals needed some organized assistance to get settled. Finding them reasonable accommodations was the first hurdle. And then there was the task of finding them employment, but this had to be done inconspicuously through silent networking. We could not let Torontonians know that we were here in any significant numbers. Remaining invisible was of utmost importance.

In the early 1940s, Toronto was still known as a Waspish town with very few visible minorities. Racial bigotry was right out in the open, especially against Jews. It was not uncommon to see prominent signs reading “Gentiles Only” and “No Jews Allowed” at some of the summer resorts like Jackson’s Point on Lake Simcoe or at some of the posh golf and country clubs in and around Toronto. This flagrant anti-Semitism was something that the Japanese Canadians could easily relate to, not just from recent memories of the expulsion and internment, but going back much earlier to days in Vancouver when some movie theatres and swimming pools excluded Asians. No mingling of the races.

Our shared experience as victims of racism somehow created a bond between the Japanese and Jewish communities in Toronto. Therefore, it was no coincidence that most of the relocees found jobs with Jewish owned firms. Some of the larger employers were Imperial Optical Company and Starkman Instruments. In addition, many members of our community, male and female, were employed in Jewish owned garment factories along Spadina Avenue. Having experienced persecution themselves, the Jews in Toronto showed their support and solidarity in the most practical manner by employing us when very few others would give us any jobs whatsoever.

As more and more Japanese Canadians drifted into Toronto during 1944 and 1945, various problems emerged. Business licences and housing were denied. Some Chinese restaurants refused to serve Japanese Canadian patrons. Some of our children faced blatant racism at school. Ironically, Mr. Trueman, the B.C. Security Commission representative in Toronto, was sympathetic to our situation. He had been sent to Toronto with the purpose of monitoring our resettlement. Since Toronto’s ban against the Japanese was still in effect, he cautioned us to maintain a low profile at all times to avoid stirring up paranoia about a “Japanese invasion” of white Anglo Saxon Toronto. We couldn’t have too many Japanese people living on the same street—or working at the same company. Trueman’s rationale was that in a city the size of Toronto, as long as you were careful to avoid attention, the number of relocees would go relatively unnoticed. Despite the negative message of concealing one’s “Japaneseness”, Trueman’s advice was actually quite sensible given the fact that Canada was still at war with Japan and very few Canadians at that time were capable of differentiating between race and nationality. It was probably safer if strangers just assumed that we were Chinese Canadians.

Getting Organized

The resettlement plan worked out reasonably well, but the needs of the new relocees in Toronto kept mounting. The need for a volunteer community organization soon became apparent as more and more Japanese Canadians came trickling eastward. We formed our first organization in Toronto in 1943 under the name of the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy (JCCD). The new arrivals looked to the JCCD for assistance and the committee dealt with everything from employment, education and housing to social problems like family reunification and racism. Some of the founders of this committee were pre-war nisei leaders from British Columbia, people like George Tamaki, Kunio Hidaka, Muriel Kitagawa, Kunio Shimizu, Kay Kato, George Tanaka, Eiji Tatabe, Kinzie Tanaka and me.

Besides the usual problems of resettlement, the JCCD was faced with two highly contentious issues. The first one was the famous shoyu and miso controversy. The Japanese government, via the Red Cross and Spanish Consulate, was offering shoyu and miso paste to the relocees in Toronto and elsewhere in Canada. The JCCD took the position that this donation was some kind of surreptitious test of loyalty and should be rejected entirely. We did not want the Canadian government to later accuse us of “accepting gifts from the enemy”. After all, we were still stuck with the label “enemy aliens”. Our Canadian citizenship was meaningless since the federal and provincial governments could only see us as Japanese subjects loyal to Emperor Hirohito.

Having been deprived of shoyu and miso for years, many relocees were understandably anxious to grasp the opportunity to taste these familiar Japanese ingredients again. It was a strong temptation. Many issei and nisei failed to see the political implications of accepting an aid package from Japan. The stance of the JCCD on this issue was therefore open to a lot of criticism from our community, but we had no choice. Our underlying objective in every decision was to rid ourselves of the “enemy alien” label. We too yearned for miso and shoyu, but as members of the JCCD executive, we could not give the Canadian government any opportunity to question our loyalty to Canada.

The second issue with which we were confronted as an organization was the question of enlistment in the Canadian Armed Forces. After Canada declared war on Japan, a ban was imposed on any further enlistment of nisei since every Canadian with a Japanese face and name was viewed as a potential enemy spy. At the same time, the British Army was pressuring Canada to send over Japanese speaking citizens who could act as translators. They would be going overseas not as members of the Canadian Armed Forces, but on loan to the British Army. All of us saw the Canadian government’s distrust of the nisei as a blatant insult, but not everyone in the JC community advocated a lifting of the ban so that we could exercise our democratic rights as citizens to take up arms to defend Canada. The conflict within our community arose from the fact that some people felt very bitter towards the Canadian government because of the expulsion, incarceration and relocation ordeal and wanted nothing to do with helping out a country that had treated its own citizens so shamefully.

The JCCD wanted to hear more opinions on this heated issue so we called a public meeting at the Church of All Nations on Queen Street in Toronto. Eiji Yatabe chaired the meeting and began with a pthresentation on the impressive record of the Japanese Americans’ 100 Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team. He argued that volunteering to serve Canada in the Pacific War, putting our lives on the line, would constitute the most obvious way to demonstrate our allegiance to this country. But Yatabe was in the minority that night.

I can recall violent threats, false accusations and angry shouting matches in every direction. It was chaos. Finally, it came to a vote. Should the JCCD seek the elimination of the government policy barring Japanese Canadians from the Armed Forces? Those present at the meeting overwhelmingly rejected our proposal. I couldn’t believe the response. Then in a moment of spontaneity, the entire executive stood up and resigned en masse right then and there and almost all the male members of our JCCD executive volunteered to serve overseas once the restrictions against us were lifted. How the restrictions came to be removed and the experiences of the nisei volunteers is a fascinating story, one covered very well by Roy Ito in his book, We Went to War1. Despite my steady job at Cansfield Electric, despite my mother’s strenuous objections, I put my life on hold and donned a uniform. There was no way that I could not enlist. It was the price of leadership.

As a founding member of the JCCD, I can honestly state that we realized from the beginning that removing the “enemy alien” stigma was the only way we could start to seek justice for the wrongs committed against us. This was our fundamental guiding principle. We had to continue to demonstrate and confirm our undeniable loyalty to Canada. Clearly, our advocacy work in Toronto during the early 1940s laid the groundwork for the Redress movement that was to follow 40 years later.

It is interesting to note here that the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), under the leadership of Mike Masaoka, was determined to prove the loyalty of Japanese Americans to the United States government. He spearheaded the same military enlistment issue in the U.S. and was the first nisei to enlist in the famous 100th/442nd unit. The major difference between the two situations was the fact that the American nisei paid for their democratic rights in blood, blood spilled across the battlefields of Europe. By the end of the war, 680 were killed in action and 9,486 were wounded.2 Luckily, there were comparatively few casualties among the Canadian nisei soldiers.

After the resignation of the JCCD executive over the Armed Services issue, some of the female members such as Nora Fujita, Em Yamanaka, Eileen Harada and others remained to carry on the work of the committee under the chairmanship of Kinzie Tanaka. As a member of the executive, he too wanted to walk out in protest and sign up to defend Canada, but it was impossible since he was born in Japan and still officially classified as a “Japanese national”.

One loyal friend in the larger Canadian community was Rev. Jim Finlay of the Carlton United Church. It does not exist now, but this church once stood at the corner of Yonge and Carlton Streets. Rev. Finlay opened the doors of his church to us and even took Wes Fuijwara’s sister, Muriel Kitagawa, along with her husband and four children, into his own home on Wellesley Street until they could find adequate housing.3

Our association with the United Church led to the formation of the Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians (CCJC), an ad hoc committee, including non-Japanese Christian church workers that led the campaign against deportations and expatriations to Japan. The CCJC gained support from the Canadian Jewish Congress, the Fellowship of Reconciliation and other organizations sympathetic to our plight. Under the legal counsel of CCF Member of Parliament Andrew Brewin, and with help from the CCJC and the JCCD, we began the lobbying process in Ottawa.

Hearing the Claims

The one consuming goal in the minds of the relocees in Toronto was to seek some sort of compensation from the federal government for their enormous financial losses. We all felt that Canada must be held accountable for the injustices inflicted upon us. Organizing our fellow Japanese Canadians was not easy since we were now scattered across the country. We needed some sort of umbrella organization. The JCCD decided to take the lead temporarily by distributing a survey among the nikkei in Toronto as early as November 1946. We wanted to determine the number of claimants and get concrete figures regarding total losses. By January 1947, a national survey had been drawn up. By April 1947, the responses had been tabulated. The survey showed conclusively that losses approximating $15 million by some 2,000 claimants were at stake since everything that was left behind had been liquidated as quickly as possible by the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property and sold for next to nothing without the consent of the owners.

Armed with our survey results and evidence of the government’s obvious negligence in the confiscation of real and personal properties, the CCJC’s legal counsel, Andrew Brewin, and members of the JCCD lobbied the Secretary of State for a judicial commission to hear the claims that we had gathered. Eventually, the matter was referred to the Public Accounts Committee. Mrs. Donalda McMillan, representing the CCJC, and George Tanaka, representing the JCCD, appeared before the committee, loaded with indisputable evidence of unfair sales by the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property. A few months later, our efforts paid off as the Public Accounts Committee recommended the establishment of a Royal Commission to investigate our claims.

This commission, led by Justice Henry Bird of the British Columbia Supreme Court, was set up on July 18, 1947. It turned out to be a hollow farce specifically designed to appease us and confuse us. The terms of reference were so narrow and biased that it was virtually impossible for any claimant to achieve an equitable settlement. As an example of the ridiculous terms of reference, the onus was entirely on the claimant to prove that the Custodian did not try hard enough to obtain fair prices for confiscated property. What kind of “justice” was this? We protested vigorously against the unfair terms of reference, but to no avail.

It was time for us to strengthen our links with fellow nikkei across Canada and the United States. Fortunately, I was acquainted with Mike Masaoka, the executive director of the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). He had grown up in Salt Lake City with my wife, Mary. He kindly consented to help us get organized nationally. Mike had faced a number of the same issues that we had wrestled with in our community: the enlistment of the nisei and generational conflicts between issei and nisei. Needless to say, Masaoka’s experience, guidance and leadership were invaluable to us at this critical time in the history of our community. Under his influence, we established the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA) with chapters in all the major centers where Japanese Canadians were residing. Based on the model of the JACL, the new organization established its first headquarters in Toronto. George Tanaka became the first executive director, while I was elected president. Since both of us lived in Toronto, our city became the first headquarters of the NJCCA. Later the headquarters were rotated according to the location of the president.

Carrying on the work begun by the Japanese Canadian Citizens for Democracy, the first major task of the newly formed NJCCA was to continue dealing with the Bird Commission. In conducting the National Survey for Property Claims, the various provinces were asked to submit a summary of the claimants in their regions and their losses in order to establish a comprehensive national picture of the situation. I can still remember the countless nights we spent at George Tanaka’s home at 84 Gerrard Street East. His home served as our office, the headquarters of the NJCCA. There we were until after midnight compiling the hundreds of claims that had to be presented to the Bird Commission.

After two and a half years of intense political wrangling over the validity of the claims and the terms of reference, the net result was a settlement figure of approximately $1¼ million for a total claim of about $15 million, according to the JCCD survey. This figure was a joke, an insult. As Ken Adachi put it, “An old Issei in 1950 could stare at his cheque for $140.50 awarded as his recovery on a house in Vancouver for which he paid $3,000 in 1930 and which was sold by the Custodian for $1,200 in 1943. He could stare and stare and wonder what remote connection it had with the destruction of his life’s work and security…Losses had to be measured in terms of entire lives.”4

Unacceptable Advice

Surprisingly and regrettably, Andrew Brewin was not as committed to our cause as we had believed initially for he recommended that the Japanese Canadian claimants accept the findings of the Bird Commission and the waivers demanded by the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property—legal waivers that would prevent the recipients of any settlements from seeking future claims. As legal counsel for the Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians (CCJC), Brewin’s recommendation was a great disappointment after our years of hard work. Accepting the Commission’s findings would be like acknowledging that it was all over and done with and that the government could no longer be held accountable. Standing up in protest, Kunio Hidaka and I resigned from the CCJC. We did not want to be associated with an organization that would prevent us from seeking true justice. The Commission may have rendered us powerless with their rigid stipulations on what claims were acceptable for consideration, but we were not gullible. We were not prepared to settle for peanuts. It was a depressing ending for all the time and effort that we had put in to try to get a fair and equitable settlement from the Bird Commission.

That figure of $1¼ million was to remain etched in my mind for 40 more years. Sadly, the NJCCA remained relatively dormant until the Japanese Canadian Centennial in 1977. After the Bird Commission Hearings, the door on the property claims issue remained closed and we all directed our energy towards the task of raising our families and rebuilding our lives. But, for a handful of us, the issue of fair compensation was always there percolating at the back of our minds. There were some of us in the Japanese community in Toronto who were not going to allow Justice Henry Bird to have the last word on the matter. We always knew that one day we would try again to seek the justice that had eluded us for 40 years.

A group of Japanese Canadians taking a break from work on Premier Hepburn’s farm, July 1943.

Front Row (L to R): unknown, Mari Yatabe, unknown, Mrs. Yatabe, Mrs. Kanamaru, Niiko Nakamura. Second Row: Mrs. Kumagai, Ruby Numajiri, Grace Numajiri, unknown, unknown (wearing hat). Third Row: unknown, Mas Yatabe, unknown, Joanne Yatabe, Kay Yasunaka, unknown, Matt Matsui, unknown, Tosh Sugiman, Ken Saegusa, Roy Kumano, Frank Nakamura, unknown.(Photo courtesy Momoye Sugiman.)

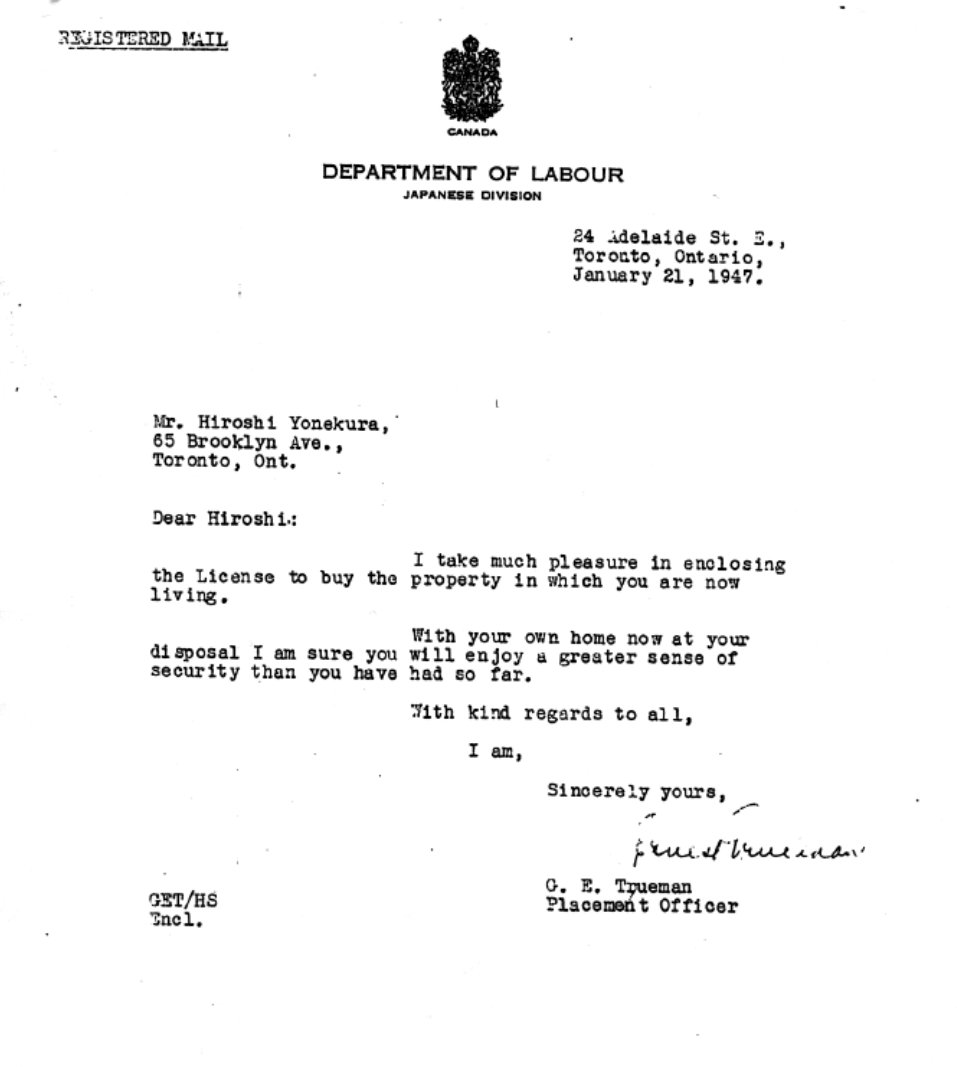

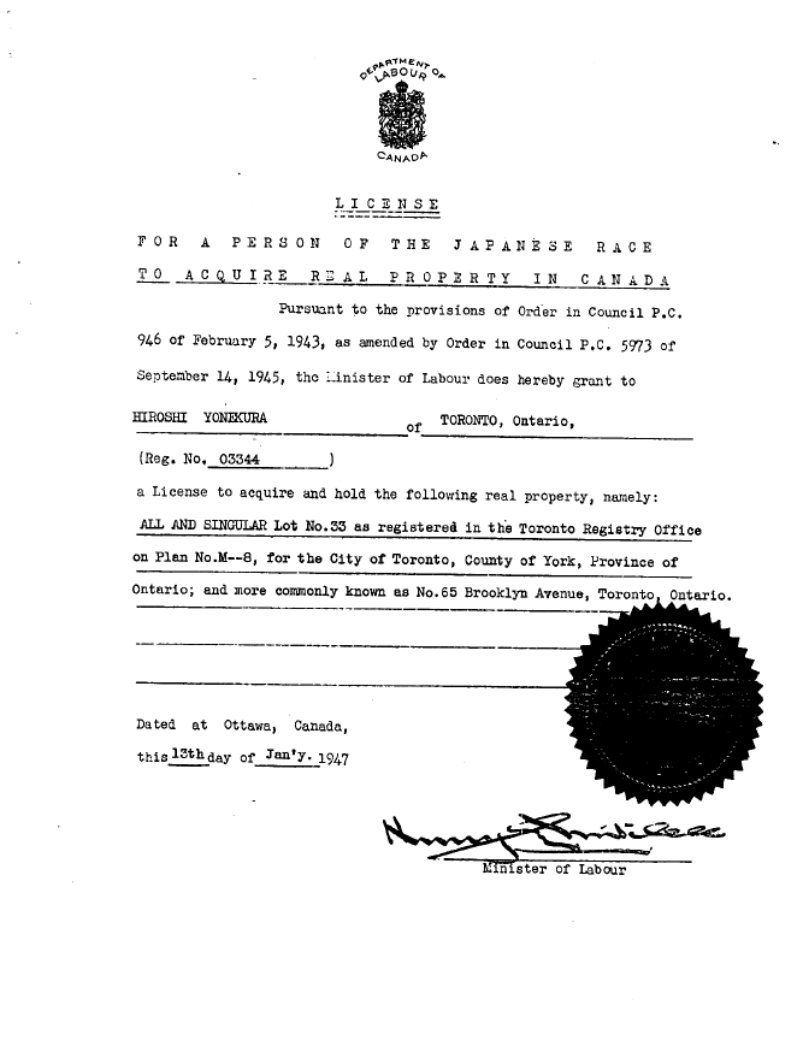

A year and a half after the end of World War II, Canadians of Japanese ancestry in Toronto still had to receive permission from the government to purchase real estate. Left: Harry Yonekura’s letter regarding the purchase of his first home in Toronto, 65 Brooklyn Ave (pictured below). Right: The actual licence to purchase the property. (Photo: Harry Yonekura)

Toronto May 1944. Just a few of the boys taking life easy on a public lawn in downtown Toronto: Tom Iwasaki, Masao Maeda, Haruo Maeda, “Tish” Tsujimura, “Susee" Hotta, Mi Akiyama. (Photo courtesy Sugiman family collection)

CCF MP Andrew Brewin served as legal counsel for the Co-operative Committee of Japanese Canadians (CCJC), an ad hoc committee including non-Japanese Christian church workers that led the campaign against deportations and expatriations to Japan. Like his CCF colleague, Angus MacInnis, Brewin spoke out vehemently in favour of granting Asians the franchise. He was one of our chief negotiators during the Bird Commission Hearings of the late 1940s. Mr. Brewin passed away in September 1983. (Photo: National Archives of Canada)

KUNIO HIDAKA was a pillar of strength in the Japanese Canadian community from the early 1940s until the formation of the Toronto “North York” Chapter of the NAJC. Born in Haney, B.C., Hidaka graduated from the University of British Columbia with an economics degree. During the expulsion years he worked for the B.C. Security Commission as a liaison person between the Commission and the Japanese community in Slocan, Bayfarm, Popoff, Lemon Creek and Greenwood. In May 1943, he moved to London, Ontario, where he worked in a steel rolling mill. He continued his education at Queen’s University, the University of Toronto and George Washington University. Kunio worked for the Ontario government in labour relations and community planning until his retirement in 1983. In the early Toronto years, he was active in the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy, assisting in the fight against deportation and participating in the Bird Commission hearings. In the 1980s he got involved in the Toronto JCCA Redress Committee and the NAJC, North York Chapter. Kunio Hidaka died suddenly on June 10, 1985, the day after he presented the results of the Price Waterhouse study of economic losses of Japanese Canadians at an NAJC Redress meeting. (Photo: Markham Photo Centre)

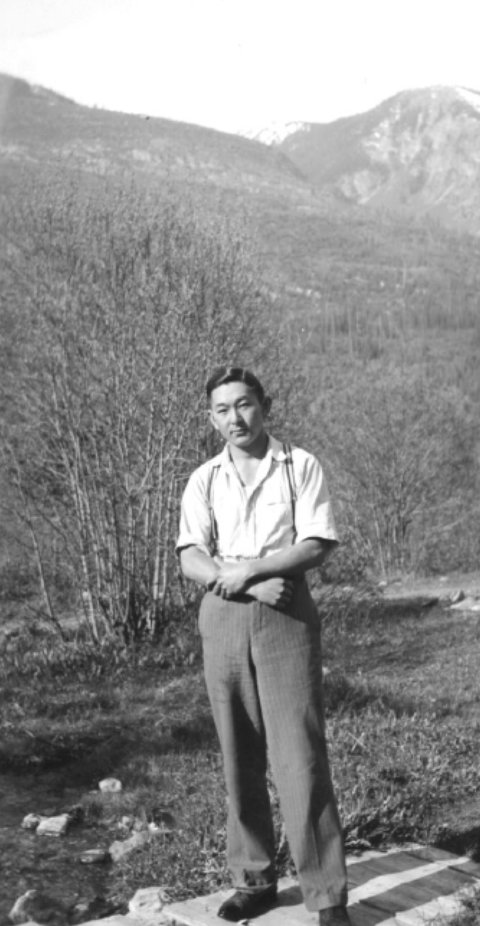

KINZIE TANAKA (shown in Lempriere Creek, B.C. in 1942) was one of the founding members of the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy (JCCD). When the executive resigned to sign up for military duty in a show of loyalty towards Canada, Kinzie wanted to join them, but he was disqualified because he was born in Japan. As chairman of the JCCD, he was left in charge of the organization, working alongside the women executive members. (Photos courtesy Kinzie Tanaka)

GEORGE TANAKA, brother of Kinzie, was not only a founding member of the JCCD, but also the first executive director of the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA). After serving in the Canadian Army, he took on this position to spearhead the Property Claims campaign of the late 1940s that led to the Bird Commission hearings. Thus, he helped lay the groundwork for the Redress movement of the 1980s. Sadly, George and his wife, Kana, were killed in a tragic car accident in 1982 before he could see the dream of Redress fulfilled.

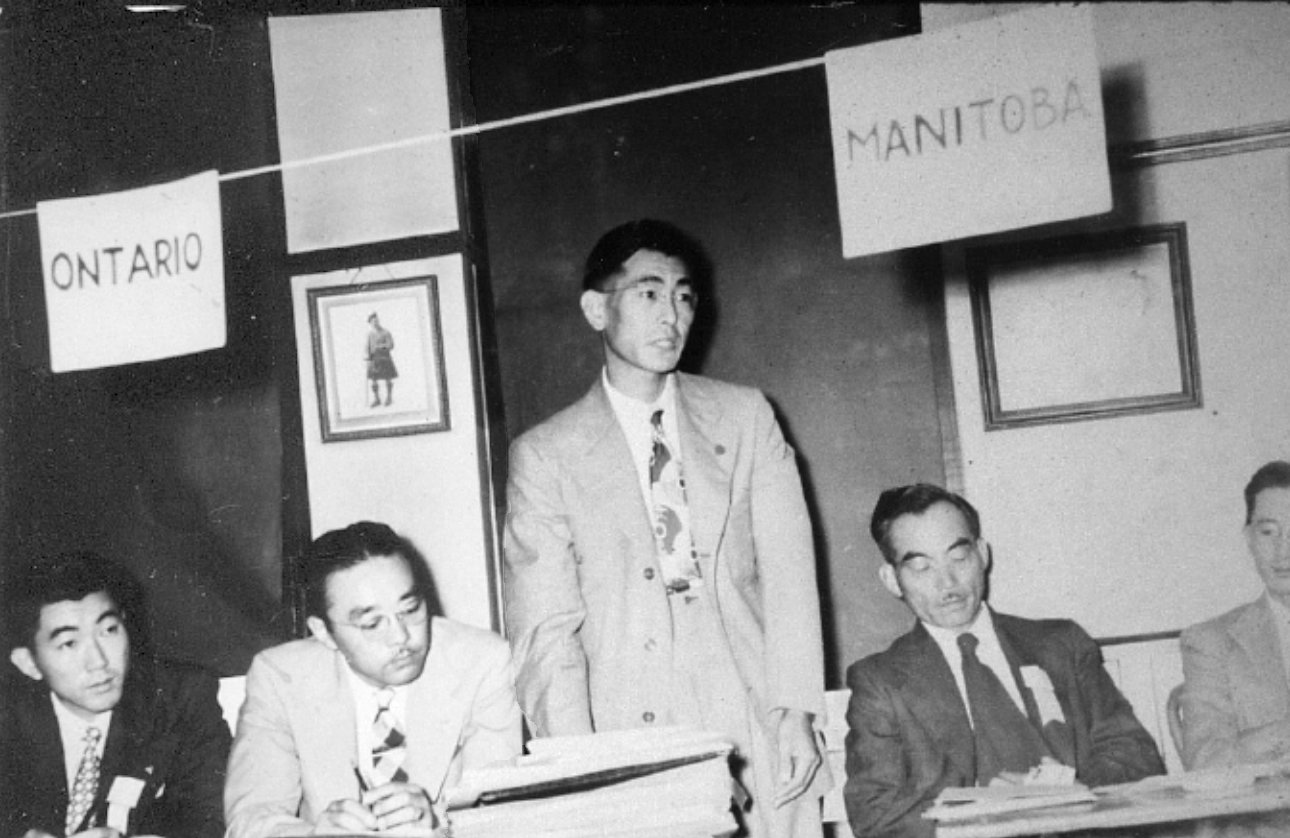

Toronto, September 1947: First conference regarding formation of National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA), renamed National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) in 1980. Left to right, Edward Ide, Roger Obata, George Tanaka, T. Umezuki and Harold Hirose. (Photo courtesy Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre)

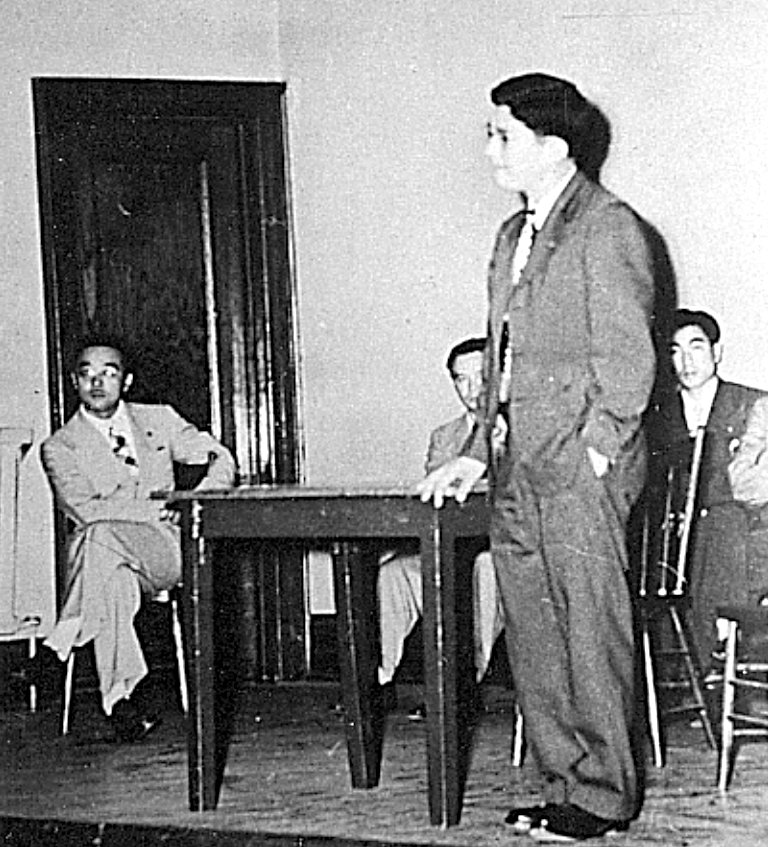

Noted American nisei community leader, Mike Masaoka, speaking at first conference of National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association, September 1947. (Photo courtesy Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre)

REV. JAMES FINLAY was a loyal friend to the Japanese Canadian community in Toronto from the early days of our relocation. During the 1940s, many nisei newcomers from B.C. were welcomed to the “House of Friendship” (the Carlton United Church) on the southeast corner of Yonge and Carlton where Rev. James Finlay was the minister. Rev. Finlay took a keen interest in the plight of the Japanese Canadians in Toronto and he helped them out in numerous ways to find housing, employment and acceptance through his church.

Later Rev. Finlay was instrumental in organizing the Co-operative Committee on Japanese Canadians, an organization which accomplished so much for the exiled JCs in dealing with the Government of Canada, particularly regarding the deportation issue. There are many JCs in Toronto who are greatly indebted to Rev. Finlay for his many acts of kindness and support during those troubled years. It was an honour to have him at the head table at the Victory Banquet in November 1988, alongside Rev. Cyril Powles, another dear friend of the JC community. (Photo: Harry Yonekura)

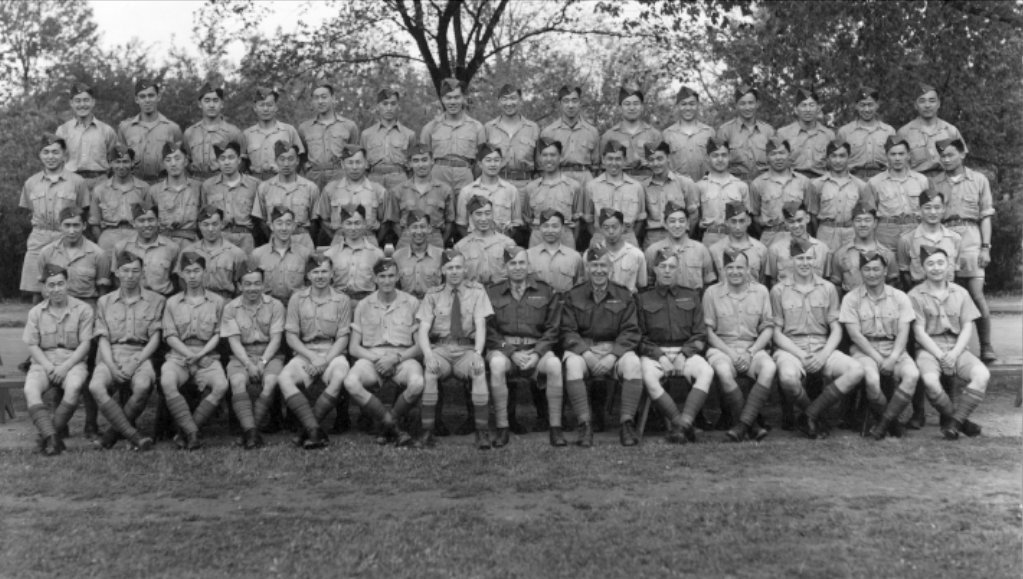

No. 17 PLATOON “B” COY. No. 20 C.I.(B)T.C.-C.A.

Brantford, Ontario, June 6th, 1945

Top Row: R. Matsui, H. Miyazawa, K.R. Oki, S. Nikaido, J. Sato, J. Goto, M. Arikado, K. Ito, G.M. Kadota, S. Oue, S. Oikawa, K. Kaneda, K. Fujikawa, M. Ono, R. Obata.

Third Row: G. Hasegawa, T. Kunitomo, T. Yamashita, A. Sato, M. Kawanami, D. Watanabe, K. Tasaka, Y. Oki, M. Yatabe, Y. Hyodo, F. Tonegawa, T. Ode, A. Sakamoto, G. Ohashi, J. Inose, H. Kunihiro.

Second Row: G. Masuda, M. Hyodo, K. Tsuchia, K. Nishio, T. Shimizu, L. Suzuki, K. Goto, J. Watanabe, K. Kitagawa, T. Nishimura, K. Nozaki, G. Shintani, K. Matsubuchi, Y. Adachi.

Front Row: K. Fujioka, E. Yatabe, R. Ito, M. Nobuto, L/Cpl. E.R. Sawyer, Sgt. G. Johnstone, Lieut. J. Marion, Maj. N.C. Bucknan, M.M., Capt. H.B. Henry, Sgt. Maj. W. Mitchell, M.M., Cpl. E. Clare, L/Cpl. E.S. Mullen, K. Kato, T.J. Oki.

(Photo: T.J. Silverthorne)

Notes

1 Roy. We Went to War (Toronto: Nisei Veterans Association, 1984), pp. 151-232.

2 Ibid., 161.

3 The Kitagawa were the second Japanese Canadian family to receive special permits from the B.C. Security Commission to resettle in Toronto.

4 Adachi, Ken. The Enemy That Never Was (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Inc.), pp. 331-332.