Chapter 13

Japanese American Influence On Our Redress

PART I: SAYING THANK YOU TO THE JAPANESE AMERICANS

By Roger Obata and Bill Kobayashi

There has been a parallel history of racial discrimination against Asians in Canada and Asians in the United States, dating back to the late 1800s. It began with restrictive immigration laws in both countries to control the number of Asians entering the country.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882 in the United States. Around the same period, the Canadian government introduced the Head Tax imposed only on Chinese immigrants entering the country. This tax began at $50 in 1885 and “gradually increased to $500 by 1904. It was replaced in 1923 by the Immigration Act “which prohibited Chinese immigration until 1947.”1 In 1891, the B.C. legislature asked Ottawa to raise the Head Tax to $200 and include the Japanese, but Japanese immigrants were never required to pay this tax. Nevertheless, the grouping together of Chinese and Japanese immigrants into an undesirable “Asiatic” class was obvious.

Following Pearl Harbor, Order-in-Council PC 365 was issued on January 16, 1942 to remove male Japanese nationals in B.C. from the 100 mile “protected zone". And on February 19, 1942 President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the exclusion, incarceration of Japanese Americans and expulsion of 120,000 from the Pacific coastal “restricted zone”. It is not surprising that the Canadian and American governments followed each other’s lead in their policies towards Asians. I believe that one can assume some degree of collaboration between the two governments.

Parallels could also be seen in citizenship and voting laws. The British Columbia government denied the franchise to Japanese Canadians, even those born in Canada. This barred them from voting in federal elections as well. In the United States, American born nisei had the right vote, but not the issei for they were ineligible for citizenship by reason of ancestry. Furthermore, they could not own property. Japanese Canadians finally gained the franchise in 1949. And in 1952, the Japanese Americans were at last granted naturalization rights under the McCarran-Walter Immigration and Naturalization Act.

In 1950 when we received the disappointing findings of the Bird Commission, we learned from Mike Masaoka (of the Japanese American Citizens League) that the Japanese American community had experienced a similar situation. Under the Evacuations Claims Act of 1948, the U.S. government tried to settle property claims for a paltry $200 for each family that filed a claim. It seemed that both governments were attempting to settle the compensation issue for less than 10 cents on the dollar.

The latest example of “collaboration” against citizens of Japanese ancestry was in the Redress settlements in both countries. This issue was by far the most significant in terms of the number of people affected and the enormous cost to both governments. The American cost was estimated to be in excess of 1.2 billion dollars and it involved about 60,000 survivors of the internment. We signed our Redress Agreement with Prime Minister Mulroney on August 26,1988, just 16 days after President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 approving Redress for Japanese Americans. Thus, in the areas of immigration, exclusion, citizenship and Redress, there appears to be a pattern of the Canadian government following the lead of the American government in policies involving its citizens of Japanese ancestry.

Mike Masaoka and Judge Marutani in Toronto

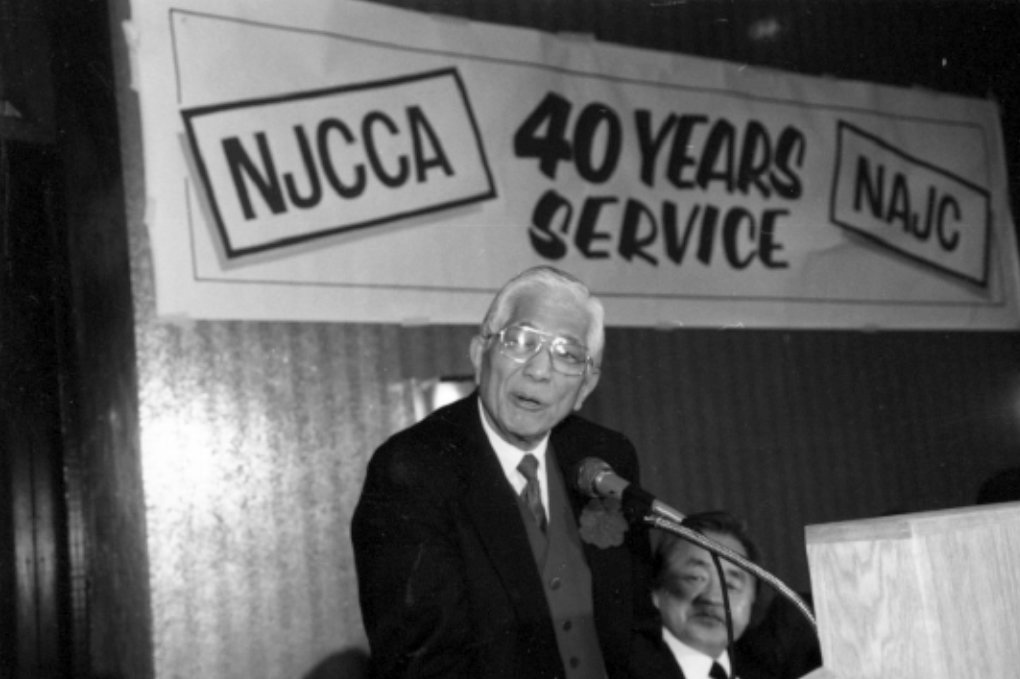

A close relationship has existed between the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) and the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA) ever since September of 1947 when Mike Masaoka came to Toronto to assist us in the formation of our national organization. The NJCCA was formed for a specific purpose of pursuing property claims”—the origin of Redress.

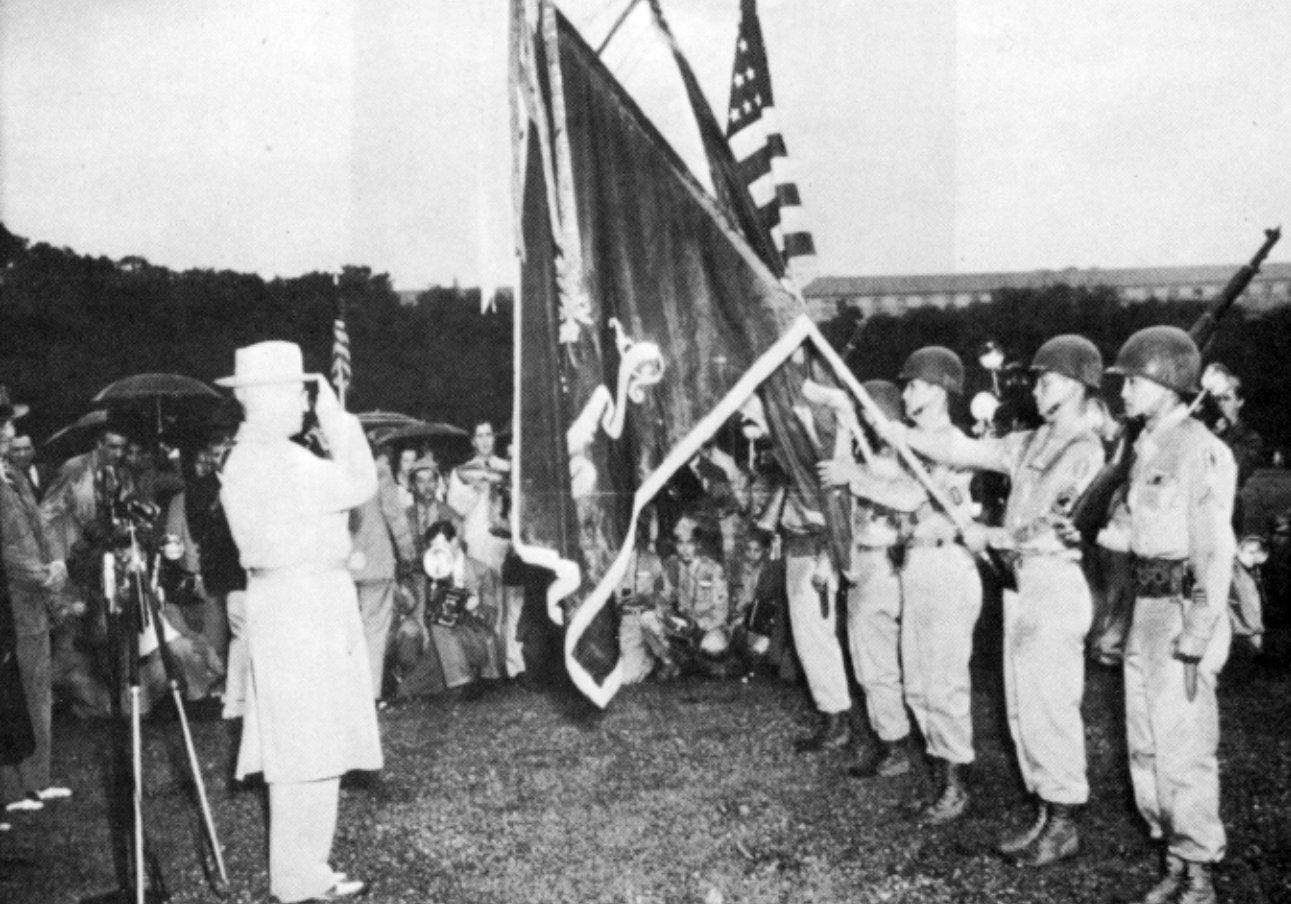

Forty years after his Labour Day weekend visit of 1947, Mike Masaoka visited Toronto again to help us celebrate the 40th Anniversary of the NAJC in October 1987. It was indeed a memorable and nostalgic occasion as four of the original founding delegates, namely Harold Hirose, Edward Ide, Roger Obata and Hiroshi Okuda, welcomed Mike to Toronto 40 years after his last visit. His keynote speech was emotionally charged as he related the incredible record of the 100th/442nd Combat Regiment in Europe, of which he was the first volunteer. The outstanding achievements of the Japanese American veterans would go down in history as an exorbitant price to pay to prove loyalty to the United States. With their valiant achievements in combat in Europe and appalling casualties, this unit was recognized as the most decorated unit of its size in the U.S. Army. However, the ironic reality was that these Japanese American soldiers achieved this distinction while members of their families were incarcerated behind barbed wire enclosures by the American government. This fact was something that the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians made known to the American public.

There is a theory that the success of Redress for Japanese Americans can be directly attributed to the war record of the 100th/442nd Regiment. I for one concur with this opinion, and go one step further to state that we in Canada achieved Redress only because President Reagan signed the Civil Rights Bill of 1988 on August 10th. After bickering with three multiculturalism ministers over a four-year period, without any success, all of a sudden our struggle for Redress was resolved within 16 days from the signing of the Civil Rights Bill in the United States. This was hardly a coincidence. It might also be said that we indirectly owe the success of our Japanese Canadian Redress to the Japanese American veterans of World War II.

When the Redress campaign in both countries began to move into high gear during the late 1970s and early 1980s, we called upon our cousins to the south to lend a hand—and they responded with their more extensive experience and political wisdom. At the first public meeting on Redress, organized by the Sodan Kai in May of 1983, John Tateishi of the JACL and William Hohri of the NCJAR in Chicago came to Toronto to speak in support of Redress.

A few years later there were two other public meetings in Toronto where Judge William Marutani of the JACL spoke at the request of the Toronto Chapter NAJC. Judge Marutani is especially noted for his work as a civil rights lawyer in Mississippi and Louisiana during the period of the late Martin Luther King Jr. and as national legal counsel for the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) during 1962-70. And in 1981, he was appointed by President Jimmy Carter as the only nisei on the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC). It was the recommendation of this commission that resulted in the Civil Rights Bill of 1988 that established Redress in the U.S. for Japanese Americans. Thus, we were able to benefit from the best Redress spokesperson available from the JACL—someone with credibility who was directly involved in the American Redress movement and other civil rights issues.

Judge Marutani spoke eloquently at the first general meeting of the Greater Toronto (formerly North York) Chapter of the NAJC about the remarkable similarities between the Japanese American experience and the Japanese Canadian experience. He not only mentioned the economic losses and violation of civil liberties, but also the “irreparable psychological damage to the individual, to the family and to the community”.2 Quoting a nisei social worker who testified before the Congressional Commission, he got across the point that the horrible experience of being incarcerated and stripped of human dignity was so traumatic that many issei and nisei repressed, denied and rationalized what happened to keep from confronting the truth that the American government was being unjust, racist—and was rejecting them. Reading from the testimony of the nisei social worker, he said, “…Like the abused child who still wants his parents to love him and hopes that by acting right he will be accepted, the Japanese Americans chose to be cooperative, obedient, and quiet Americans in order to cope with an overtly hostile, racist America…”3

Judge Marutani had no trouble holding the attention of the audience of 200 NAJC members. He cogently argued that a mere apology would never be enough to begin to heal the wounds, noting that, “[as] a judge…in the criminal courts, whenever anyone commits an offence… it is not enough for the wrongdoer to turn to the injured person and say ‘I’m sorry’…In order to make sure that he is sorry and doesn’t repeat it again, there is a monetary exchange. And it is symbolic. And the $20,000 in the United States is symbolic…It comes out to $1.2 billion, so vast is the offence.” Judge Marutani went on to say that unless money is involved, the concept of “baka ni sareru” comes into play, that is, “there’s a point where you cannot back off; otherwise baka ni sareru.” He explained that this phrase means, “you are made a fool of; you are being taken advantage of; in other words, you’re a dope.”4 He pointed out that backing off and remaining passive might still be acceptable in an Asian country, but operating according to such cultural ethics in the U.S. [and thus in Canada], renders one a fool.

Judge Marutani’s speech was an eye-opener for many nisei in the room. It left all of us with a lot to ponder, not only about the Redress issue, but also about our inner selves. He helped fuel our determination to seek individual compensation by underscoring the fact that our experience in Canada was fundamentally the same as that of our American counterparts, and that we had every right and obligation to hold out for a meaningful settlement.

President Reagan Signs Redress Bill

We learned a great deal from the example set by the Japanese American Redress movement. The lobbying necessary to get the Civil Rights Bill of 1988 to the final stage for President Reagan’s signature took almost five years of concentrated effort and perseverance on the part of the JACL. This monumental task was undertaken by the JACL’s Legislative Education Committee (LEC), under the chairmanship of Min Yasui, a well-known leader of the JACL who had defied the government on the mass exclusion from the California coast. Min Yasui recruited Grant Ujifusa as vice chairman of the LEC since “Ujifusa was uniquely suited to help Japanese Americans thread their way through the maze of the U.S. Congress. As co-author of the Almanac of American Politics, Ujifusa brought political savvy and a detailed knowledge of the inner workings of the Hill to the campaign for redress. He also brought entree to the offices of most members of Congress.”5

Grace Uyehara was appointed executive director of the JACL-LEC. She was a spunky woman who impressed me with her articulateness and dedicated drive for the Redress cause when I met her and her husband in Calgary. She, along with Grant Ujifusa, was responsible for coordinating the lobbying both in the Congress and in the Senate. In the House of Representatives, they worked closely with Congressmen Norman Mineta and Robert Matsui and in the Senate with Spark Matsunaga and Dan Inouye. Guiding the lobbying strategy of the JACL-LEC was Mike Masaoka who had many years of experience in Washington behind him.

The intensity of this time consuming work of contacting each and every congressman and senator took almost three years of unrelenting effort on the part of the three people on the lobbying team: Grace Uyehara, Grant Ujifusa and Mike Masaoka. As executive director, Grace was responsible for the letter campaigns, petitions and telegrams to the members of the House and Senate seeking support for the Redress bill. In addition, support was solicited from all sympathetic organizations both Japanese and non-Japanese in this common struggle for justice.

The strategy of the JACL-LEC apparently worked as “the Senate finally passed the redress bill, financial restitution and all, on April 20, 1988 on a 69-27 vote. The long battle for approval of redress was over.”6 The final step was the signing of the bill by President Reagan. There was considerable concern over how he would react to this bill in the face of so much opposition from “outraged veterans.” It was the expertise and experience of Grant Ujifusa that guided the final stages to a successful conclusion. Ujifusa enlisted the support of Governor Thomas Kean of New Jersey who was successful in influencing President Reagan to some degree towards his decision to sign the bill. On August 10, 1988, “in an emotional ceremony attended by over 100 Japanese Americans and key members of Congress, the president briefly recounted the story of the internment…” The following are excerpts from President Reagan’s remarks that day:

Thank you all very much. The members of Congress, and distinguished guests, my fellow Americans, we gather here today to right a grave wrong. More than 40 years ago, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in makeshift internment camps. This action was taken without trial, without jury. It was based solely on race—for these 120,000 were Americans of Japanese descent.

Yes, the nation was then at war, struggling for its survival and it’s not for us today to pass judgement upon those who may have made mistakes while engaged in that great struggle. Yet we must recognize that the internment of Japanese Americans was just that—a mistake. For throughout the war, Japanese Americans in the tens of thousands remained utterly loyal to the United States. Indeed, scores of Japanese Americans volunteered for our Armed Forcend—many stepping forward in the internment scamps themselves. The 442th Regimental Combat Team made up entirely of Japanese Americans served with immense distinction—to defend this nation, their nation. Yet at home, the soldiers’ families were being denied the very freedom for which so many of the soldiers themselves were laying down their lives…

The legislation that I am about to sign provides for a restitution payment to each of the 60,000 surviving Japanese Americans—of the 120,000 who were relocated or detained. Yet no payment can make up for those lost years. So what is most important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor. For here we admit a wrong. Here we reaffirm our commitment, as a nation, to equal justice under the law…Blood that has soaked into the sands of a beach is all of one color. America stands unique in the world, the only country not founded on race, but on a way—an ideal. Not in spite of, but because of our polyglot background, we have had all the strength in the world, that is the American way…

Thank-you and God bless you. And now let me sign H.R. 442—so fittingly named in honor of the 442nd 7

Conclusion

There is little doubt in my mind that the Civil Liberties Bill of 1988 would not have become a reality had it not been for the indisputably, magnificent war record of the 100/442nd Regimental Combat Team. After all, this important bill was designated HR 442 for that specific reason, and President Reagan recognized this significance at the signing of the bill.

Japanese American veterans had paid a high price in blood on the beaches of Cassino and in the Black Forest of France to prove their loyalty to the American flag. My brother-in-law, Edward Ogawa, who served in the 100/442nd unit, is buried in a military cemetery in France where he was killed in rescuing the “Lost Texas Battalion”. This magnificent war record played a major role in the success of the Japanese American Redress campaign.

It became the job of the JACL-LEC to ensure the recognition of these sacrifices by loyal American citizens of Japanese ancestry on the battlefields of Europe. The outstanding effort of this group of Japanese Americans, along with the invaluable support of the Japanese American congressmen and senators, had a tremendous influence on many politicians. The passage of Bill HR442 in the Senate and the House of Representatives was a monumental feat.

We owe our achievement of Redress to the Japanese Americans, both World War II veterans and the JACL-LEC. I have taken the initiative, as an individual, to convey the gratitude of the Japanese Canadians to the Japanese American Citizen League and to my friends such as Mike Masaoka, John Tateishi, Judge Bill Marutani and Grace Uyehara. I have personally thanked the Japanese American Veterans at the various reunions that I’ve attended, but we as a national organization have done little in a formal, official way to acknowledge their contributions to our Redress. Let us hope that this book will communicate the debt of thanks of all Japanese Canadians to their Japanese American cousins who have done so much to assist us in achieving justice after more than 45 years.

PART II: U.S. CONSULATE DEMONSTRATION

AUGUST 15, 1988

By Bill Kobayashi

The Japanese American Redress movement was watched closely by the National Association of Japanese Canadians, recognizing that Canadian politicians would be greatly influenced by the U.S. decision. A number of American nisei came to address our community during our Redress campaign of the 1980s. People such as Mike Masaoka, Judge Bill Marutani, William Hohri and John Tateishi kept us apprised of the U.S. movement. In 1988, the movement was gaining support in Congress, but there was always the spectre of a presidential veto.

Therefore, in early 1988 when I visited a cousin in Los Angeles, an assistant director of public works for Los Angeles County, I asked, “What do you think about the possibility of President Reagan’s veto?” My cousin replied, “There are a number of influential nisei in the Republican Party in California who are putting the pressure on Reagan to pass the bill.” Consequently, on August 10, 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Bill authorizing Redress for Japanese Americans.

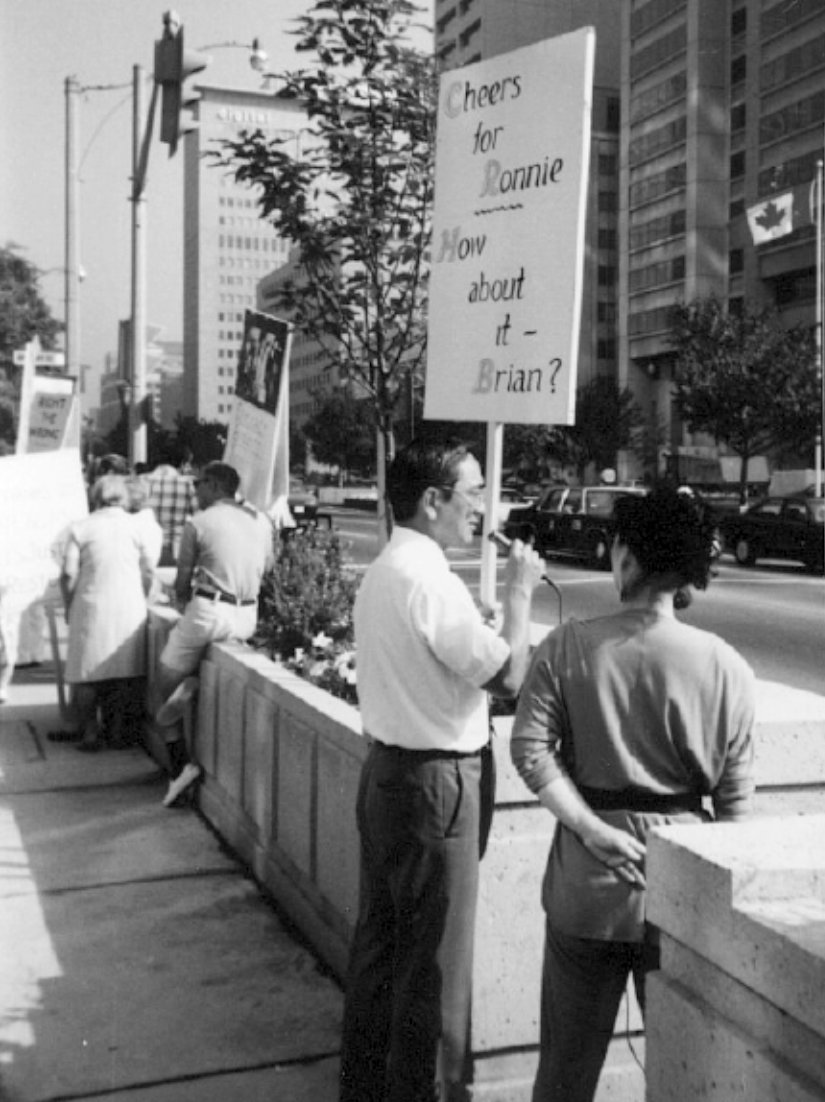

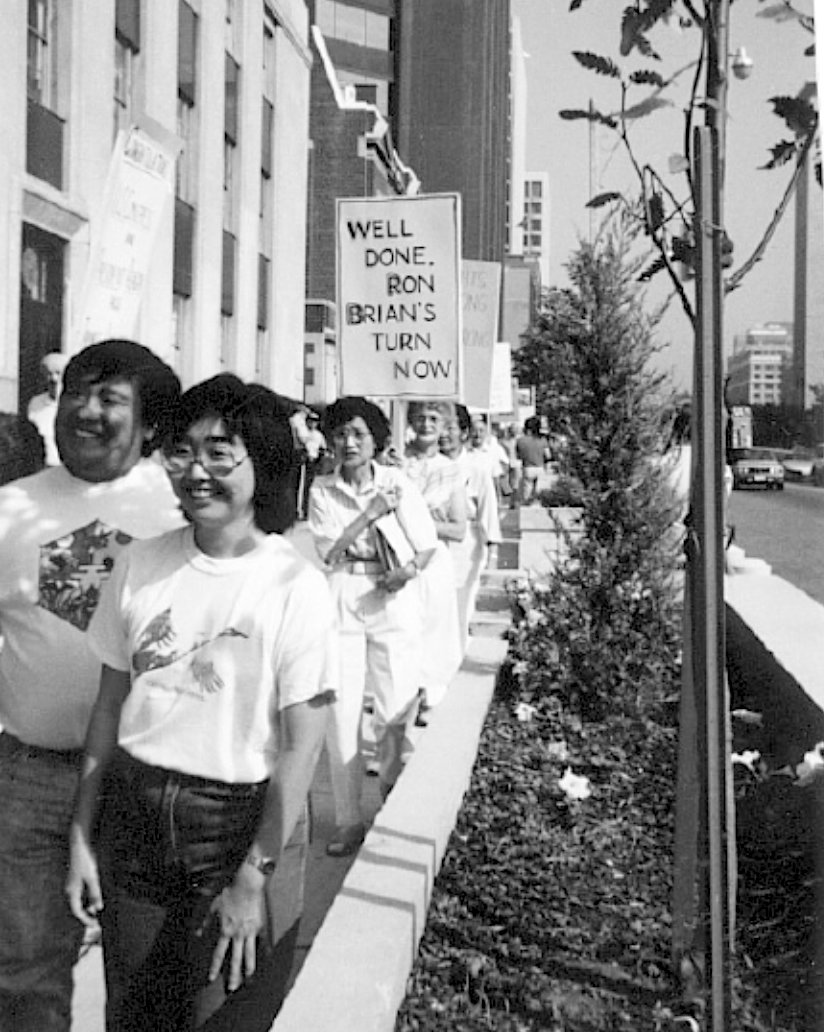

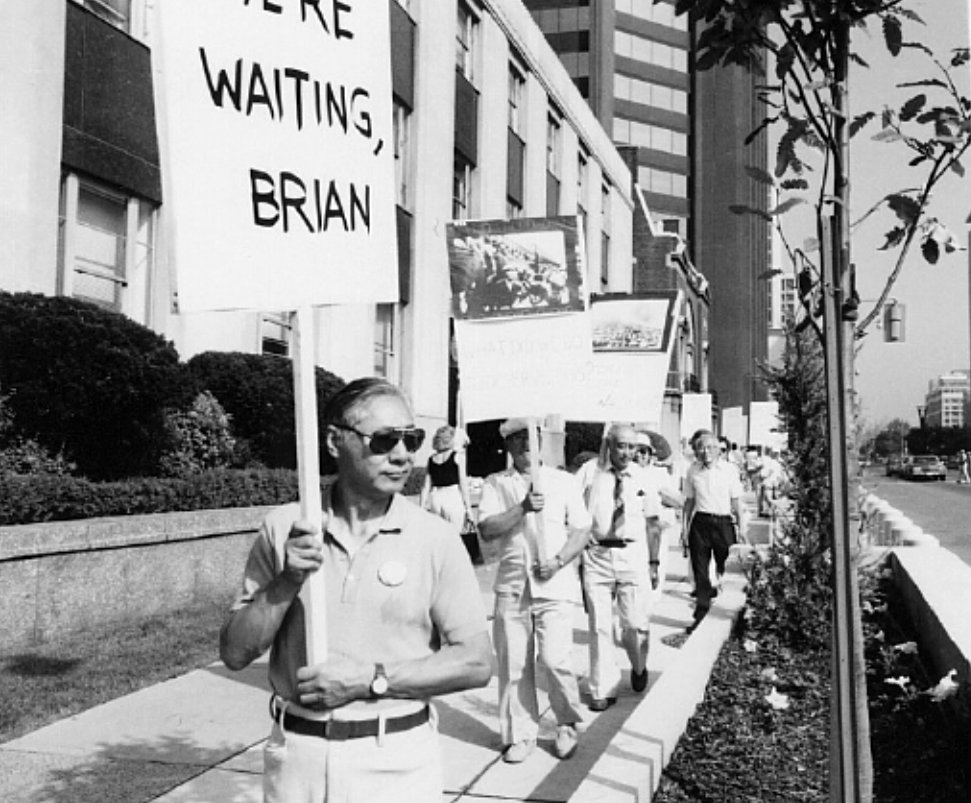

The NAJC Toronto Chapter planned to capitalize on the U.S. decision with some form of public display to draw attention to our cause. Van Hori organized a demonstration at the U.S. Consulate on University Avenue near Dundas in downtown Toronto. The date was set for August 15, 1988. Fortunately, Van secured a permit from the Metro Toronto Police on the condition that pedestrian traffic not be impeded—fortunate because when the demonstration started, we were confronted by the RCMP security who eventually allowed us to continue.

Unlike most demonstrations, this one was unique because we were not protesting against anything. We were there to praise the actions of the U.S. government and President Reagan. The ulterior motive was that we hoped to shame the Canadian government and Prime Minister Mulroney into following the example set by the Americans.

Before the demonstration, I contacted the United States consul general, John Hall, for an appointment with our representatives to congratulate the American government on their landmark decision. He declined to meet with us, presumably to avoid the perception of meddling in Canadian internal affairs. However, at the start of the demonstration, I entered the U.S. Consulate and tried again unsuccessfully to get an appointment to meet John Hall. As a last resort, I asked, to no avail, if he would just step outside and acknowledge our presence with a wave. We hoped that our designated photographer for the event, Fred Kagawa, could get a shot of him. But he refused to oblige.

While I was in the Consulate a security guard rushed in announcing the presence outside of “demonstrators with signs”. Immediately, the guard was instructed to lock the doors and allow only people with “legitimate business” to enter singly. I advised them not to fear since it was a friendly demonstration, not one that would erupt in violence.

We had spent days preparing for this demonstration by making placards and trying to figure out what wording we should use on the signs. It took the combined effort of many heads to think up the most effective wording. Many NAJC volunteers came out to march up and down in front of the consulate. Yo Mori’s sign read, “THANKS, RON. WE’RE WAITING BRIAN”. Other signs read, “CHEERS FOR RONNIE, HOW ABOUT IT BRIAN?” and “U.S. RIGHTS THE WRONG, WHAT’S WRONG WITH CANADA?” And there was also one that read, “RIGHT THE WRONG—REAGAN YES—MULRONEY???”

The whole purpose of the demonstration was to gain some valuable publicity for our cause and this was certainly accomplished with Stum Shimizu waving his sign at curbside all afternoon. The usually heavy University Avenue traffic slowed down as drivers observed this unusual scene.

We even made the evening news on CITY TV’s news program, “City Pulse”. Interviews by reporter Thalia Assuras of Roy Sato, Mary Obata, Mae Ogaki and Roger Obata were shown on television that night. As this event was part of our public education campaign in support of Redress, it was felt that we had scored a few more points in our crusade for justice.

In spite of the 30-degree plus weather, 50 or more came out to help, some for short periods from breaks from downtown offices. Photographs by Fred Kagawa show Matthew and Polly Okuno, Sab Takahashi, Reiko Mizuyabu, Yo Mori, Terry Watada, Blanche Hyodo, Dave and Aiko Murakami, Hedy Yonekura, Dorothy Kagawa, Kay and Ted Hayashi, Matt Matsui—and several others pacing back and forth with their signs. A welcome treat was when Wes Fujiwara appeared with cans of soft drinks for the thirsty demonstrators.

What influence this demonstration might have had in the final decision is difficult to determine, but we can safely guess that it had some impact. On August 26, 1988, eleven days after our appearance outside the U.S. Consulate, the NAJC negotiating committee was called to Montreal and was able to negotiate a satisfactory Redress agreement, an agreement that became public on September 22, 1988. No doubt the American Civil Rights Bill of August 1988 was a model for the Canadian Redress Settlement.

President Harry S. Truman awarding Presidential Unit Citation to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Comprised of the 442nd Infantry Regiment, the 232nd Engineer Company and 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, this team was the most decorated unit of its size in the U.S. Army. Most of the military awards were for individual acts of bravery. The awards for Purple Heart number more than 9,000. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a unit made up of Japanese American soldiers, received the following decorations for participation in seven major campaigns in Europe:

- 7 Presidential Unit Citations

- 9,486 Purple Hearts

- 1 Congressional Medal of Honor

- 52 Distinguished Service Crosses

- 1 Distinguished Service Medal

- 588 Silver Stars (28 of the Silver Stars were awarded a second time)

- 22 Legion of Merit Medals

- 5,200 Bronze Stars (1200 of the Bronze Stars were awarded a second time)

- 15 Soldiers Medals

- 14 French Croix de Guerre

- 2 Italian Crosses

- 2 Italian Medals for valor (Photo courtesy Jack Wakamatsu)

Above and below: The Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team in the field, France, 1944. (Photos courtesy Jack Wakamatsu)

Mike Masaoka, a veteran of the 100th/442nd Combat Team, was instrumental in the formation of the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Associatiothn. He came to Toronto in 1947 to help us get organized and returned in 1987 for our 40 Anniversary Celebration. (Photo courtesy Roger Obata)

JUDGE WILLIAM (BILL) MARUTANI is familiar to most Japanese Americans because of his regular column in Pacific Citizen, a Japanese American community newspaper—and his long history of fighting for human rights, not only for Asian Americans but Black Americans as well. We were very fortunate to have his personal input during our struggle for Redress in Canada. He spoke at public meetings in Toronto at the invitation of the NAJC Toronto Chapter. (Photo courtesy Roger Obata)

President Reagan signing HR 442, the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 on August 10, 1988, which authorized Redress for Japanese Americans. Japanese Americans attending ceremony were, from left to right, Senator Spark Matsunaga, Representatives Norman Mineta, Patricia Saiki, Robert Matsui, and JACL President Harry Hajihara. (Photo courtesy Rita Takahashi)

NAJC DEMONSTRATION ON UNIVERSITY AVE. IN FRONT OF U.S. CONSULATE, AUGUST 15, 1988

(Photos: Fred Kagawa)

Recognized in first photo: Dorothy Kagawa. Recognized in second photo: Hedy Yonekura, Reiko Mizuyabu, Dorothy Kagawa and Blanche Hyodo.

Dorothy Kagawa, HedyYonekura and Kay Hayashi in front of U.S. Consulate.

Recognizable in photo: Yo Mori, Ko Ebisuzaki, Dave Murakami and Matt Matsui.

Roger Obata being interviewed by CITY-TV’s Thalia Assuras.

Recognized in this photo: Polly Okuno, Bill Kobayashi and Aiko Murakami

Recognized in first photo: Terry Watada and his wife, Tane, Polly Okuno and Blanche Hyodo. Recognized in second photo: Blanche Hyodo, carrying sign.

Notes

1 The Women’s Book Committee, Chinese Canadian National Council. Jin Guo: Voices of Chinese Canadian Women. (Toronto: Women’s Press, 1992), p. 17.

2 Chiba, C.M. “Voices of Inspiration—United States Judge William Marutani Speaks At Greater Toronto Chapter, NAJC General Meeting". The Canada Times. March 7, 1986.

3 Marutani, William. [speech] February 9, 1986. Delivered at first general meeting of Greater Toronto Chapter, NAJC at Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, Toronto.

4 Ibid.

5 Case Program C16-90-1006.0. Harvard University.

6 Ibid.

7 Reagan, Ronald. [speech] August 10, 1988. Delivered on the occasion of signing Civil Rights Bill of 1988 in Washington, D.C.