Chapter 2

Our Expulsion Stories

Part I: The East Lillooet Independent Group

By Stan Hiraki (with the assistance of Blanche Hyodo)

In 1942, I was in my final year of high school. I planned to stay in Vancouver to finish my senior matriculation. Thus, in the spring of that year, I said good-bye to my mother, Sawa Hiraki, and my three siblings as they set off for East Lillooet. My father, Chikai Hiraki, was a naturalized Canadian, but even so, was one of the earliest issei to be sent to a road camp. By choosing to be “self-supporting”, he was allowed to join his family in East Lillooet.

I was allowed to complete my high school education, but I couldn’t attend my own graduation banquet and dance because of the curfew imposed on all Japanese Canadians at the time. By the summer of 1942, many members of our community were confined to Hastings Park. I decided to spend my summer as a volunteer, teaching grade four students in a makeshift school in the arena at Hastings Park. When the Hastings Park School closed, the volunteer teachers were given a crash course in teaching, after which I finally left Vancouver and headed for East Lillooet to join my family.

Accompanying me on the journey was an old family friend, Dorothy Okuma, known at that time by her Japanese given name, Nobuko. She had also taught at the Hastings Park School and her parents were close friends of my parents, both having come from Saga-ken. Also, like my folks, hers had been expelled to East Lillooet, B.C. in the spring of 1942, where they had built their home next door to ours.

The Union Steamship Lines took Dorothy and me to Squamish, British Columbia. At Squamish we boarded a train to the town of Lillooet in the B.C. interior and then a “stagecoach” (so called in those days, although it was nothing more than a passenger car) took us to our final destination, East Lillooet, across the river from the main town of Lillooet. It was 11:00 p.m. when we finally arrived, exhausted and hungry after our long inland journey. But even had we been wide-awake, neither Dorothy nor I would have been prepared for what we saw. Having lived my entire life in the city of Vancouver, with all its modern conveniences, the dismal rows of dimly lit shacks in otherwise utter darkness was incredibly depressing. I felt we had retrogressed to the Dark Ages.

Before coming here, the B.C. Security Commission had assured Bunjiro Hisaoka, our community liaison person, that East Lillooet was a well established community with all the modern facilities and electric lighting. Not until too late did we learn the terrible truth about our “self supporting” community.

Paying the Price for Family Unity

The concept of the “self supporting” scheme was born out of a desperate need to discover a means by which families could be allowed to remain intact. Government policy to date had been to send the adult males to road camps, leaving wives and children to fend for themselves until the government relocated them to government sponsored ghost town settlements. Unlike the Japanese Canadians who were sent to the ghost towns, those who chose to go to East Lillooet received no government assistance since they were considered independent. In order to qualify for the new “self supporting” program, the government stipulated that families had to have at least $1,800. Ultimately, about six different “self supporting” communities were developed in the rugged territory of the B.C. interior—in places such as Minto, Christina Lake, Bridge River, McGillivray Falls, Taylor Lake and East Lillooet. As the name implies, “self supporting” meant assuming complete responsibility, financial and otherwise. This was the alternative we were given if we wanted to keep our families together. We had to use our hard earned life’s savings to pay for our own imprisonment!

My arrival in East Lillooet was some six months after my family had arrived. By then every JC family there had managed to build a crude one-room shack partitioned or curtained off to separate the bedroom from the combined living room/kitchen. There was no electricity and there was no water. A 45-gallon drum had been converted into a wood burning “stove” which served, inadequately, to heat the shack. Just before leaving Vancouver, I purchased a small wood-burning cook stove. Until it arrived, my family was without any property cooking facilities.

Most of the families in East Lillooet were average working people. Some were small businessmen like my father who had owned and operated a 44-room, three storey rooming house on Keefer Street in Vancouver. Others were fishermen and boat builders from Steveston, and farmers from Haney. With absolutely no help from the government or any other outside source, these families demonstrated their resilience and resourcefulness by building their own homes. They also managed, under the most difficult of circumstances, to obtain their own supplies of water and firewood. Basic survival skills perhaps, but nonetheless a remarkable feat.

Never Taking Water and Heat for Granted

That first winter in East Lillooet was exceptionally cold with temperatures hovering around minus 30 degrees Celsius. The intense cold represented an additional hardship when it came to obtaining water. The Fraser River was only accessible at a site some 1,000 feet or so away. By the time I arrived in East Lillooet, there was a well-worn path leading to the river. Here we could fill our water cans (much lighter than buckets) with relative ease, and suspend them from either end of a wooden pole to be carried across our shoulders for the long trek back. I never did master this technique. Once, during one of my water fetching excursions, I found myself waist deep in the frigid Fraser River after accidentally stepping on a thin patch of ice. Somehow I managed to save myself from drowning and I ran all the way back to our shack as quickly as possible to avoid freezing to death. By the time I reached the familiar rows of shacks, my trousers were frozen stiff!

Once the water was safely transported from the river to our shacks, we faced the onerous task of preparing it for drinking purposes. This involved a purifying procedure whereby we filtered the water through a box of sand and charcoal. It was then boiled for several minutes before it was fit for human consumption. These incredibly time-consuming and labour intensive tasks were extremely hard on the men, women and children who learned to perform them on an almost daily basis. The irony was that once we had only to turn on a tap for the same results! We will not easily forget the long and difficult tasks we underwent in order to drink a glass of clean water.

Heating the shacks demanded even more physical exertion and mental determination, but it was imperative that we find a way to keep warm. The alternative in that sub-zero weather was death by freezing. The wood-burning, 45-gallon drum stoves used to heat our shacks needed a constant supply of wood. We therefore had to trudge through the snow a considerable distance from our community to an area that contained more suitable trees. However, even then the wood was not free. It was necessary to pay stumpage fees to the landowner. After felling the trees, we chopped off the branches and sawed the trees into six-foot lengths. The next step was to load the logs onto sleds and pull the heavily loaded sleds through the snow all the way home. Back then, we were not allowed to own trucks, and the B.C. Security Commission had long since confiscated any vehicles that we had once owned. Thus, we had to rely on the combined strength of our own arms and legs to transport the wood to our shacks. But even after our arduous trek home, the work was not yet done. The six-foot lengths had to be sawed into shorter ones, and then chopped into much smaller pieces to facilitate the burning of mostly green lumber. To keep the firewood dry we built storage sheds. The prolonged, backbreaking labour did not come easily to us former city dwellers.

Frozen Ink, Icy Outhouses and the Promise of Spring

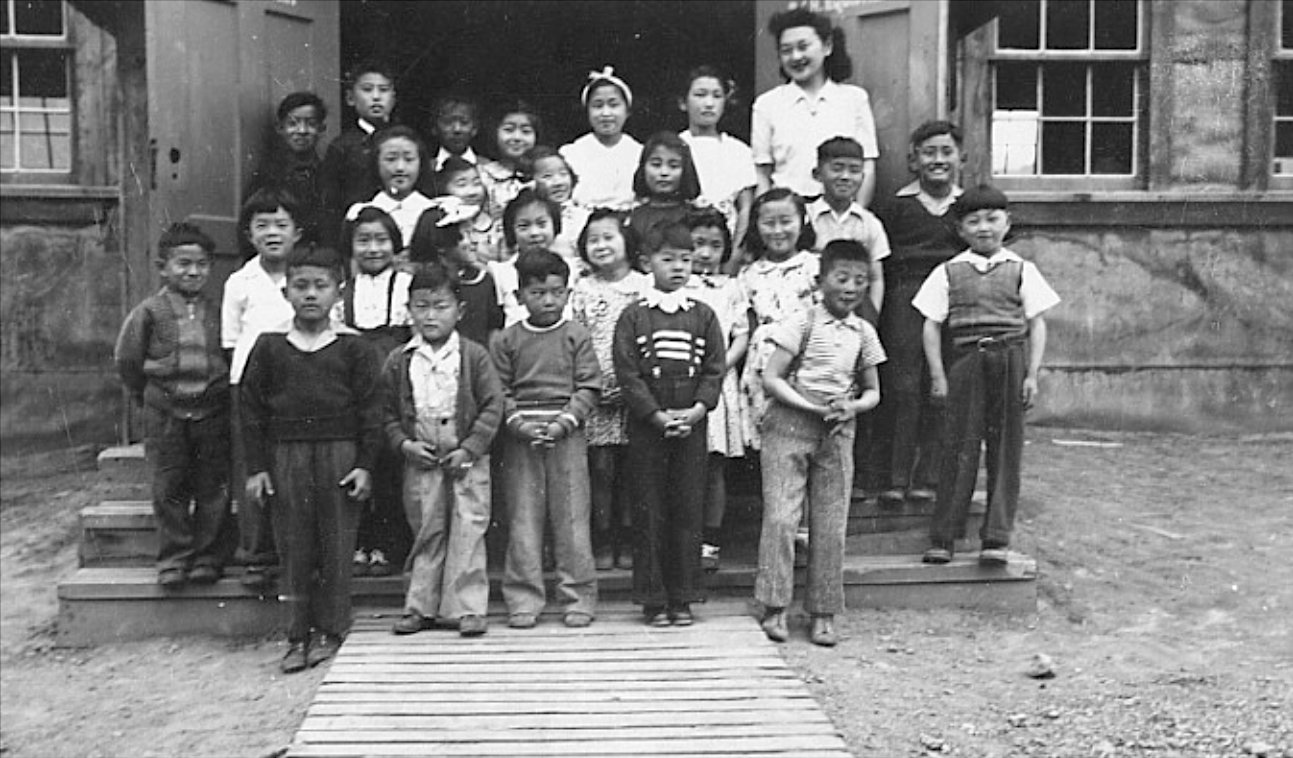

Schooling for the children in our community was an immediate concern. For the time being, we organized classes for them in a large tent. Volunteers built two-seater desks for the students, but lack of space precluded any desks or chairs for teachers. Dorothy Okuma and I shared the teaching duties equally. While Dorothy taught the four lower grades, I taught the four higher ones. We used plywood sheets painted black as our blackboards. At first, we had only one piece of chalk each. It is interesting to note that while the ghost town teachers received a monthly salary of $45 from the B.C. Security Commission, we were given an honorarium of only $5 a month by the ijikai (parents’ association). Furthermore, the commission assumed responsibility for the education of the ghost town children, while neither a schoolhouse nor supplies was provided for the Japanese Canadian children of East Lillooet. We were on our own.

The weather soon grew too cold to continue classes in the tent. By mid-November, the new schoolhouse was completed and Fumi Kono was added to our teaching staff. At the same time, I was appointed school principal. The schoolhouse was divided into two rooms with a solid partition down the middle. Dorothy taught grades one to three in one room, while Fumi and I taught the upper grades in the other.

That first winter the temperatures were unbearably cold. On these days, students and teachers wore jackets and mitts during class in an effort to keep warm. The walls of the school were lined with tarpaper and 45-gallon drum stoves were installed, one on either side of the partition. But, this heating system was far from adequate. The ink froze in the inkbottles and we had to line them up on a shelf beside the stove to thaw. The relentless elements proved too much for the makeshift heating system, but, of course, it was better than nothing.

Having lived in Vancouver all my life, where the winters were relatively mild compared to East Lillooet, I simply didn’t own any heavyduty boots or winter coats such as the polar conditions of East Lillooet warranted. Much of our winter clothing had to be ordered from the Eaton’s catalogue store in Winnipeg and we had to wait for it to be sent to us via stagecoach. We found it easier to choose clothing from the catalogue, which featured a wide variety of colours, styles and sizes, rather than walk or bike four miles to the store in Lillooet. Footwear was another item that we had to worry about. With all the walking, pulling and carrying that we did, our shoes wore out quickly. Some families replaced them with hand carved wooden clog-type shoes held on by a piece of belt across the top of the foot.

With no indoor water facilities, we had to build outhouses. These were located behind the shacks and some distance away. A trip to the outhouse in wintertime was an agonizing ordeal. How I dreaded that ice cold seat! It was bad enough during the day, but we couldn’t bear the thought of going out into the pitch-blackness of night to find our way to and from the outhouses through the deep snow and howling wind. Therefore, our family, like many others, kept a 4-gallon covered tin inside our shack. It was emptied in the outhouse each morning.

Our bedroom could best be described as wall-to-wall beds. We were a family of six and even though we doubled up, there just wasn’t enough room for an aisle between the beds. We had to crawl over the end of the bed in order to get into or out of it. Before going to sleep for the night, we would load as much wood as possible into our drum stove and bank it so it would burn slowly. Invariably though, the fire burned out long before sunrise. When we opened our eyes in the morning, the shack was bitterly cold—so cold that the walls and floorboard nail heads were covered in frost.

There were times, however, when we actually enjoyed the cold weather. I remember ordering a pair of ice skates from the Eaton’s catalogue and praying that they would fit when they finally arrived. We played ice hockey on the frozen Fraser River, using wooden pucks, which we sawed from puck-sized tree trunks or branches. Rubber pucks were too expensive and one good swing with a hockey stick often meant the loss of a puck in the deeper, unfrozen area of the river. So we learned to bank the snow up to prevent losing our pucks. With replaceable wooden pucks, the inevitable loss wasn’t such a disaster as we usually had an ample supply of them on hand. With next to no manufactured goods around, we learned to be innovative with whatever was available. Whoever said, “necessity is the mother of invention" sure had that right!

In springtime, to supplement our food supplies, we cultivated garden plots between the dirt road and the river. In order to irrigate these plots, it was necessary to build a wooden flume and to install a gas driven pump beside the river to force the water up the flume. As well, wooden holding tanks at intersections provided an all-purpose supply of water for bathing, drinking and laundry. The drinking water still required purifying, but at least we were saved the hardship of fetching and hauling it home everyday from the river. Other types of food and supplies were purchased from an enterprising hakujin (i.e. white) tradesman who owned a grocery and dry goods store in town. Once or twice a week he drove his truck to East Lillooet, took our orders and delivered them to us a few days later.

As spring set in, life in East Lillooet was beginning to get a bit easier. We were growing our own produce and were getting weekly deliveries of food and other staples from the town. By 1944, drinking water was being trucked in from the town as well. Each family owned a water barrel and paid 15¢ for a barrel of water. This ended the onerous task of water purifying that had consumed so much of our time and energy. We purchased a naphtha gas lamp for the kitchen/living room area, as it was cleaner and burned more brightly than the coal oil lamp. However, naphtha gas lamps were expensive, so the coal-oil lamps remained in the bedroom and ofuro (or Japanese style hot tub).

In the summertime, bathing was no problem since we swam in the river everyday. However, this was not possible during the winter. Because we had no communal bathhouses nearly every family had their own wooden ofuro, located in a small wooden shed attached to the shack. The initial soaping and scrubbing was performed before entering the ofuro. During the winter, this cleansing process was uncomfortably chilly. But soaking in the steaming hot ofuro was utter bliss, and made the preliminary soaping and scrubbing in the cold shed worthwhile. To prepare such a bath, a fire was lit beneath the ofuro several hours in advance to ensure that the bath water was hot when you needed it. These hot tubs were built by the Steveston boat builders in our community—men who were skilled in the art of leak proofing.

In December 1944, I left my family and friends in East Lillooet and ventured to London, Ontario where I worked in the dining room of St. Peter’s Seminary. And in the spring of 1947 I moved to Toronto and arranged for my family to join me.

Looking Back on the Ordeal.

The desperation and constant frustration experienced during that first year in East Lillooet gradually began to fade through the combined cooperation of the entire community. Life would never be easy for us there, but we had met the challenge of the wilderness and survived through sheer ingenuity and hard work. I look back on those days with a sense of pride in our accomplishments.

The punishment that we were forced to endure as a result of ignorance and racial discrimination tested our endurance to the limit. Had we been criminals, the government would have provided us with food, shelter and the necessities of life. But as law-abiding citizens, we were treated far worse than thieves and murderers. Our only “crime” was that our features and names resembled those of the enemy. For that we were branded “enemy aliens” by our own government, not only during World War II, but also for years after the war ended.

Many Japanese Canadians to this day believe that those of us in the Lillooet self-supporting group were the lucky ones simply because we got to spend the war years in a camp of our choice without government interference in our lives. On the surface, the concept must have seemed enviable to those who were in road camps or prisoner of war camps, separated from their families. However, the reality of our situation in East Lillooet was a far cry from the superficial image of independence and self-sufficiency. This “self supporting” group experienced a much harsher ordeal than most other Japanese Canadians.

One is tempted to compare our life in East Lillooet to that of the early pioneers in Canada. But the pioneers had the advantage of choosing their sites for building homes and settlements, giving careful consideration to such amenities as firewood, access to water sources and fertile land. Those of us who were misled into going to East Lillooet were virtual exiles in our own country, forced to use some pretty desperate measures under equally desperate circumstances. How we survived the harrowing ordeal, both physically and psychologically, will always amaze me.

Part II: The Story of Yukiharu Mizuyabu

By Yukiharu Mizuyabu

I was living in my birthplace, Nanaimo, B.C., in December of 1941. My parents, both naturalized Canadians, had five other children—my two older sisters, two younger brothers and a younger sister, all born in Canada and, therefore, Canadian citizens. When Canada declared war on Japan, the citizenship of our family members was totally irrelevant to the politicians and bureaucrats who could only see our Japanese faces and our Japanese names. Through their racist eyes, we were all enemy aliens regardless of our citizenship status.

At Brechin School, the public school attended by almost all Japanese Canadian children, we were made to feel like we no longer belonged. We were immediately excluded from the cadet training which all the boys our age had been taking since the war in Europe. The German and Italian boys were allowed to continue their training, despite the fact that their ancestral countries were at war with Canada long before Japan entered the scene. It was obvious that we were being treated differently from all the other children. I don’t think we were told not to come to school anymore, but we all dropped out some time after the fall of Hong Kong, which I recall as the last item of news about the war I heard on the school’s newly installed PA system. Our Japanese language education was also brought to an abrupt halt as the government ordered the immediate closure of the Nanaimo Japanese Language School.

Like many other men in Nanaimo, my father was a fisherman. He was lucky because he owned a salmon trolling licence for summer and a cod-fishing licence for winter. These licences were coveted items since the government was perpetually tightening restrictions for “Japanese” fishermen. My father was a highly skilled fisherman. The income he earned from his catches was more than adequate to support his large family. He owned one of the biggest one-man operated fishing boats in the Strait of Georgia, built less than three years earlier at the famous Kishi Boatbuilding Yard in Steveston. In addition, my father was able to buy us a newly built house on a large double lot.

Our relatively tranquil life took an unexpected turn when the war with Japan started. All Japanese fishermen were ordered to stay in port. Soldiers equipped with bayonets on their rifles stood along the waterfront road to ensure that the Japanese Canadians abided by the curfew imposed upon them. A few weeks later, my father and all other JC fishermen were ordered on to their boats and escorted by the Canadian Navy to the mouth of the Fraser River near New Westminster where the boats were impounded. They were then forced to return to Nanaimo by ferry, possibly never to see their boats again. Without their boats, all JC fishermen were suddenly deprived of their only source of income, but the callous politicians made no provisions for the families affected by these actions.

Leaving Nanaimo

Around March 1942, we began to hear rumours of Japanese Canadians in the outlying coastal areas being rounded up and sent to internment camps. Soon, JC families in Nanaimo began to slip away, one after another, with intentions of joining relatives in Steveston or Vancouver or even the B.C. interior, perhaps naively believing that they could avoid expulsion and internment by living with relatives on the mainland.

After mid-March, the only Japanese Canadians left in Nanaimo were our family and a childless couple, who were waiting around for the balance of payment for their recently sold property. The husband was an ex-fish buyer who had carried on a lucrative business before the war.

My father was puzzled about our next step so we visited the local provincial police station to ask what we were supposed to do. The police officer pointed his finger at my father and then, turning to me, a thirteen year old interpreter, he uttered, “You tell your father he has to leave right away!” But what about the rest of our family? According to the police officer, the rest of us were allowed to stay. My father had no intention of seeing his family split up, but he instructed me to tell the police officer that he would comply with government orders.

A week or so later, the childless couple who were still in Nanaimo apparently received the balance of the payment for their property. They had been staying with us in our attic since the sale of their property. They suggested that the two families leave together for Vancouver. But before leaving, my father thought that we should let the police know he was now going, so he and I again went to the local B.C. police station. The same police officer was there. As soon as he saw my father he shouted, “What? You still here!” I remember the rage in his eyes. I was terrified that violence might erupt. I don’t know exactly how I managed to placate the angry police officer, but I think I said something like, “We’re all going now—for sure.”

My father had already arranged with a real estate agent to have a white Canadian family rent our house as soon as we left. We moved all our belongings, including some of my father’s fishing equipment, into the basement, leaving the main floor and attic to the tenants. And then we waved good-bye to our cherished home and boarded the CPR ferry Princess Elaine for the journey across the strait to Vancouver. During the crossing, the ex-fish buyer’s wife promised my mother that our two families would stick together, but the promise was short-lived. As soon as we landed, RCMP officers, who appeared to have been waiting for us, shoved our family of eight into two taxis. We were whisked away to the infamous Hastings Park, home of the Pacific National Exhibition. This was the holding area for Japanese Canadians before being carted off to their more permanent camps in the B.C. Interior.

Remembering the Degradation

Food and accommodations at Hastings Park were very poor by Canadian standards, even for that time, but obviously the government deemed them good enough for “enemy aliens”. Hundreds of women and children were squeezed into the livestock building, each family separated from the next by a flimsy piece of cloth hung from the upper deck of double-decked steel bunks. The walls between the rows of steel bunks were only about five feet high, their normal use being to tether animals. There was no barrier to reduce the noise of crying babies or the sound of animated conversations. Until I got adjusted to the constant cacophony of voices, it was impossible for me to sleep.

Our “toilets” were sections of a long metal trough with running water, attached to the outer wall in one part of the building. Pieces of 2 x 4 lumber, attached to the edge of the trough away from the wall, functioned as our toilet seats. Stalls with no doors separated the users from each other. It goes without saying that responding to the call of nature was no longer a private act. The lack of sanitary, private toilet facilities became an even more degrading experience when we were fed what we suspected was rotten hamburger meat. Many of us were unable to reach the metal troughs in time. After the second outbreak of diarrhea, there was a minor riot. Eventually, they stopped feeding us “rotten” meat.

While the government had planned nothing for the education of the children at Hastings Park, young, better educated nisei who were still living freely on the outside, volunteered to teach the children. A school was started in the indoor basketball stadium. Our teacher was Mr. Namba who was too passive and good-natured to discipline the boys in his class. One day when the boys refused to obey his instructions to get up on the stage with the girls to rehearse for a school concert, we had exhausted his patience and he sent us to the principal for punishment. He lined us up in a row with our palms held out and hit each of us once or twice. He struck very hard and when it was all over the stick had broken into three or four pieces. It was so painful that one boy sobbed audibly, while the rest of us did our best to conceal our pain. I remember being struck one extra time simply for answering a negative tag question, quite unconsciously, in the Japanese way, instead of the English way. The question was something like “You won’t disobey a teacher again, will you?” The Japanese way is to agree that you won’t by simply saying “yes”, meaning “yes, that is so.” On the other hand, the English response would be “no, I won’t.” So if the question is “You won’t do it again, will you”, then a “yes” response in Japanese means that you won’t do it again. “No” means you will do it again. The reverse meaning is the case in English. Obviously, Mr. McCrae misunderstood me, interpreting my affirmative response as another act of defiance.

After our episode with the principal, many of the boys stopped attending this makeshift school. It was easy to get away with absenteeism since our mothers had no idea how we older children were spending the day once we got out of bed in the morning. We were relatively free to do as we pleased because our most important need, food, was provided at the communal mess hall and at our age we didn’t have to be accompanied by an adult.

During our six-month internment at Hastings Park some of the children picked up bad habits. I was certainly no exception. Emulating some of the men who whiled away the time gambling, I soon learned how to play poker, gin rummy and blackjack. We removed the price tags from 5-cent peanut bags to use as our make-believe money for our card games. Looking back, I often wonder how this early introduction to gambling affected the later lives of the children of Hastings Park.

While we were still at Hastings Park, a naval officer informed my father that his fishing boat had been sold. My father was outraged. “Who gave the consent?” The officer replied that it had been a man named Kimura who was one of the Japanese Canadians appointed by the government to advise on the disposal of Japanese Canadian fishing boats. The government had empowered itself to sell JC-owned boats with or without consent. But to cover up the injustice of their actions, the bureaucrats responsible for the liquidation of JC property engaged some Japanese Canadians to act as token consultants. They probably felt that if they mentioned a Japanese name as the person who advised the sale, the owner would be more agreeable to signing the agreement of sale. Venting his anger against Mr. Kimura, my father refused to sign the document. Although I was only 13 years old at the time, I remember thinking that my father’s anger was misplaced. Whoever this Kimura was, he was unable to defy the government when asked to be an advisor.

A Bizarre Excursion

My parents had not expected to be away from home for such a long time. When our stay at Hastings Park grew into months, they became obsessed with the thought that they might never see the money that they had buried in the basement. So they contacted a JC middleman in Vancouver, a man who was in the business of assisting Japanese Canadians in their dealings with the authorities. I don’t know the details of the negotiations that transpired between this man and the RCMP, but it was all pretty fascinating to me.

One day, my parents were called out to the main gate of Hastings Park. I accompanied them as an interpreter. An RCMP officer in civilian clothes, accompanied by his wife, was waiting for us. They beckoned us into their private car and we were driven to the CPR wharf to catch the ferry to Nanaimo. Surprisingly, after disembarking, the RCMP officer and his wife departed in an opposite direction, perhaps for a sightseeing tour of Nanaimo. We felt bewildered by the fact that we were not being treated as dangerous criminals out on day parole. Left to ourselves, we walked the streets of Nanaimo freely and headed for our house north of the city. It was bizarre. We were supposed to be “enemy aliens”, inscrutable saboteurs, yet here we were on Vancouver Island again without an armed guard. Apparently, no one who knew the Japanese Canadians on an individual basis truly believed the government propaganda describing us as “threats to national security”—not the RCMP officer, not his wife and not any of the people who saw us as we walked to our house.

The woman of the family renting the house ushered us into our home, seemingly unalarmed by our presence in town. While I did my best to keep her engaged in conversation, my parents went to the basement to dig up the money. We then returned to the Nanaimo CPR wharf as scheduled to meet the RCMP officer and his wife for the return trip to the mainland. The entire excursion was actually fairly pleasant and civilized. After we got back to Vancouver, the officer and his wife drove us back to Hastings Park where we resumed our life as internees in a prison for Canadian citizens who had committed no crimes.

Our Lemon Creek Shack

Around September 25, 1942, we finally left the stench of Hastings Park and boarded a train for the overnight trip to Slocan City, a cluster of old, Wild West type wooden buildings on the south end of Slocan Lake, approximately 300 miles from Vancouver. From there we were transported by truck to an open field two miles away. Our family of eight was assigned temporary accommodation in a canvas tent measuring 12 X 12 feet. This ordeal lasted for two weeks until we were loaded into a truck again to be taken to Lemon Creek, a camp about five miles away. Here the government, using the labour of JC internees at 15 to 25 cents per hour, had built hundreds of shacks for about 1,700 people.

Each shack measured 14 x 28 feet and was divided into three sections, a 10 x 14 foot section at each end and an 8 x 14 section in the middle. The walls separating the sections had doorways but no doors. The end sections had double-decked wooden beds with straw-filled mattresses. The middle section, our combination living room and kitchen, had a wood burning stove for heating and a wood-burning kitchen range. There was no plumbing and no electricity. Several families shared an outhouse behind the shacks and a water tap located beside the road in front of the shacks. Because our family consisted of more than five individuals, we were the lucky ones. We did not have to share a shack with another family. Lemon Creek was extremely cold in the winter and quite hot in the summer. But the shacks had no insulation. The walls of our shack were one layer of thin wooden board covered with two-ply paper sandwiching a flimsy layer of tar. There was no ceiling below the roof. In the winter, moisture condensed on the inside of the cold walls and turned to ice.

After the tent mess hall was closed, the internees were required to cook their meals using the cast iron, wood-burning cook stove installed in each shack. They purchased food from the two stores set up in the camp for internees to purchase food and other essentials. Those who had no personal funds that the government was aware of were given a living allowance for food and clothing. Our family was refused the allowance because the government was holding the net proceeds from the sale of my father’s boat until he signed the papers consenting to the sale. The money held for him was increased while we were in Lemon Creek, when the government sold his house. Again, as in the case of his boat, the sale was made against the expressed wishes of my father. The government officer who denied him living allowances for his family told him that he would receive $75 a month from these funds if he would simply sign the consent papers. Refusal to comply meant that we would starve. Given this ultimatum, my father finally gave in and we received $75 of our own money every month. Thus, we were forced to pay for our imprisonment out of our own pockets—a requirement not even imposed upon hardened criminals in any penitentiary of the world.

Although Lemon Creek had no barbed wire fences, it was situated in a narrow valley enclosed by mountains, making it difficult for anyone to escape. A mile or so south of the camp, there was an RCMP post on the only route for vehicles. As a thirteen year old, looking up at those huge mountains that surrounded the camp, I felt like I was looking at unscalable prison walls. I remember wondering when I would ever be released from this natural prison.

The government provided a semblance of education for elementary school children in the camp, but nothing for high school students. So we were forced to build our own high school using left over scraps of lumber. A church in Eastern Canada sent us two male and two female teachers; in addition, one or two teachers were recruited from among the more educated internees. When the school was ready to receive students, I had a lot of catching up to do since I had already lost a whole year of schooling.

From about 1944, the internees were allowed to leave the camp to work as farmhands in interior B.C. communities because Canada, like many countries involved in the war, was suffering a labour shortage. In the summer of 1945, I left the camp for the first time to work in Kamloops. While working there on a Chinese Canadian owned farm, I learned of Japan’s surrender. World War II had come to an end. Automatically assuming that we could now begin to rebuild our lives back in Nanaimo, I returned to Lemon Creek to reunite with my family. I was surprised to discover that the ordeal was not over yet. The government refused to release us from our imprisonment unless we agreed to relocate east of the Rockies—or repatriate ourselves to Japan. The rationale behind these ridiculous conditions could no longer be attributed to “national security”. Clearly, the only reason was to satisfy the racists who wanted to banish us forever from the Pacific coast of Canada.

The level of racial hatred generated by B.C. politicians and journalists at the time was incredible. Newspapers reported that they had received letters from the public urging the removal of Japanese Canadians. Roy Ito notes in We Went to War: “Bruce Hutchison of the Vancouver Sun informed the office of the Prime Minister that the newspaper was ‘under extraordinary pressure from [its] readers to advocate a pogrom of Japs. We told the people to be calm. Their reply was a bombardment of letters that the Japs all be interned.’”

The word, “pogrom”, as I understand it, means “organized massacre”. Today, Canada is so quick to condemn “ethnic cleansing” when it occurs in other parts of the world, but just 50 years ago, Canada was itself guilty of “ethnic cleansing” by driving us out of our places of birth on the coast of British Columbia, herding us like cattle into prison camps and then forcing us to relocate east of the Rockies.

Exiles in Japan

By the summer of 1946, the government was still denying us freedom of movement in this country, our native land. I had had enough of this shabby treatment and so I chose to be exiled to Japan along with the rest of my family. The Canadian government liked to use the euphemism “repatriation”, but this was a misnomer. “Repatriation” means returning to one’s home country, not going to a country that you have never seen before. Until 1946, I had never known any country but Canada.

When we arrived in Japan in August 1946, the country was in ruins. Indiscriminate bombing had flattened all the major cities, except for the ancient capital of Kyoto. Tokyo and Osaka were mounds of rubble. In addition, the military forces of the United States and her allies now occupied Japan. Despite the presence of the occupation forces, I felt free for the first time since being imprisoned in Hastings Park at the start of my teenage life. I was now 17½ years old.

Life in Japan during those post-war years was harsh. Bare necessities were scarce. Compared with our pre-war life in Nanaimo, we were living in abject poverty. But we were free and treated fairly. Although we were soon showing signs of malnutrition, I refused to entertain thoughts of returning to Canada or applying for a job with the American occupation forces. The mistreatment I had received from the Canadian government had made me regard Americans with the same disdain I held for Canadian politicians. However, after almost two years of starvation existence in my father’s old village, I succumbed to the lure of a full stomach of nourishing food and went to work for the American military.

I was surprised to discover that the Americans respected my Canadian birthright and treated me not as a recent enemy, but almost as an ally. Japanese Canadians working for the American military, to the chagrin of Canadian officials, were treated not as Japanese nationals, but as “foreign nationals”. As the Canadian government’s post-war policy was not to allow any persons of Japanese ancestry to return to Canada, regardless of their Canadian citizenship, the Canadian officials were concerned that the “foreign national” identification cards, given to Japanese Canadian employees of the American military, might somehow be used as travel documents to return to Canada. The American authorities assured them that the cards could not be used as such. Getting to know the American military men on a personal basis, I gradually broadened my perspective and changed my previously one-dimensional view of white people. I realized that in every group, there are good ones and bad ones, while the majority fall into various categories in between.

While working for the Americans, I learned that the Canadian government had finally given its citizens of Japanese ancestry the right to vote and was willing to accord them the same status as any other citizen of Canada—on paper at least. I was also informed that the Canadian government office in Tokyo was accepting applications for “clarification of Canadian citizenship” from all Japanese Canadians living in Japan, including those who lived through the war in Japan and those “repatriated” to Japan after the war. To me, an exile who had been goaded into signing a statement renouncing my Canadian citizenship prior to my so-called “repatriation” to Japan, the purpose of the application seemed rather whimsical. If the government had legitimately extracted my renunciation statement, it should be demanding that I now apply for a pardon (for whatever wrong I had committed against Canada) and a restoration of my citizenship. Perhaps the politicians in Ottawa were now trying to hide from the rest of the world the shameful manner in which they had driven us into renouncing our Canadian citizenship. Perhaps they wanted to avoid the publicity that might result if the government were to require us to plead for the restoration of our citizenship in court.

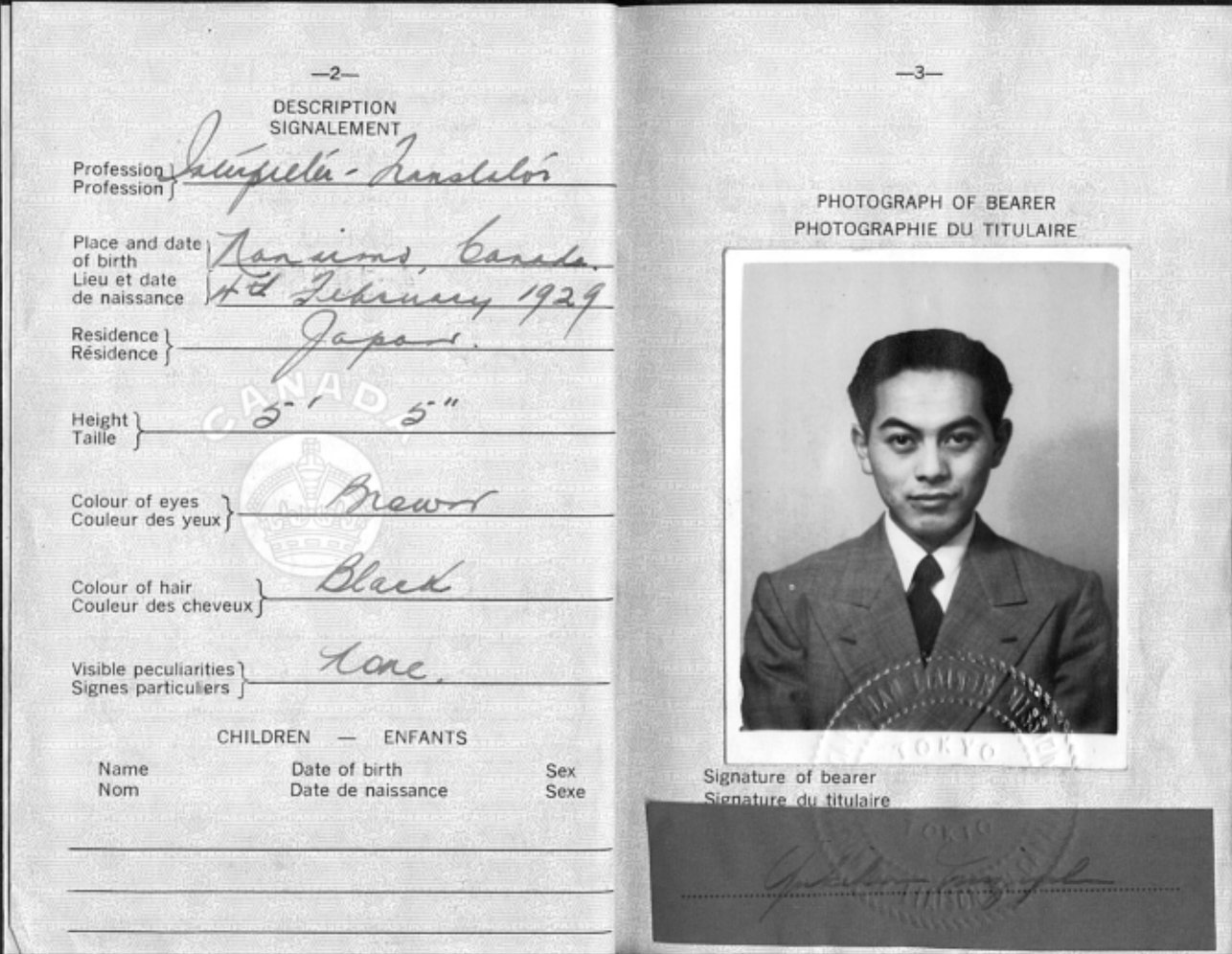

I gave considerable thought to this change of heart in my native land. The Japanese people had been very good to me. Despite the harsh post-war conditions, they had let us share equally in the meagre amounts of necessities of life available. Food at that time was in such short supply that, in my parents’ village, the daily ration provided only 1,000 calories and consisted of some food that was so unpalatable that I could not swallow it. I was getting used to life in Japan and I appreciated the politeness and general sense of honesty and fairness in the society. However Japan was crowded. I missed the wide-open spaces of Canada—an environment that would probably be better for raising children. I also felt a growing need to return to Canada to fight for my rights, rights that had been ruthlessly trampled on. So, in 1951, five years after vowing never to return, I applied for “clarification” of my Canadian citizenship and received a Certificate of Canadian Citizenship from Ottawa.

Many years later, during the days of the Redress movement, I learned that this so-called clarification of Canadian citizenship still did not give me exactly the same rights as a European Canadian residing outside of Canada. For example, German Canadians who had been abroad during the war were offered government-paid passage back to Canada if they had no funds of their own. There was no similar offer of financial aid to destitute Japanese Canadians wanting to return to Canada. In fact, even after 1949 when Japanese Canadians were supposedly given the same rights as other Canadians, any Japanese Canadian who wished to return had to have someone act as a sponsor as an assurance that he or she would not become a public burden. Thus, we would be treated like new immigrants even though we were coming back to our native land. Many Japanese Canadians returned to Canada by entering into labour contracts with Ontario mushroom farmers who paid their passage and acted as sponsors in exchange for a guarantee of three years of labour.

In order to pay for my passage back to Canada, I went to work for a Japanese construction company in Okinawa in 1952. It was one of the many Japanese and American construction companies engaged by the U.S. government to convert Okinawa into what the Japanese press called an “Unsinkable Aircraft Carrier”. Four months into the job, the Americans asked me to work for them directly, offering to pay me a salary that I could not refuse. This well-paying job kept me in Okinawa for another nine years, but I never abandoned my original plan of returning home to Canada. During those nine years, I ended up marrying a woman from Okinawa and becoming the father of two boys. By 1961, when I finally decided to return to Canada, the U.S. military— continuing to respect my Canadian citizenship—offered my family and me free passage to wherever my home in Canada happened to be. I gave the address of an uncle who by then had returned to Vancouver.

Assessing the Past

Personally, I feel fortunate to have survived the hardships of my exile in Japan. I will always feel deeply indebted to the United States government for reversing my fortunes after I was kicked out of Canada by my own government. I also feel indebted to the people of Japan for welcoming me, for helping to alleviate my feelings of rejection, for allowing me to share equally in the very little food available in Japan during the immediate post-war period.

When I wonder what might have been, I think of my late father as well as many other JC fishermen. If the mass expulsion had not occurred, I suspect that he would have become a millionaire in his profession, instead of being dependent in his final years on the meagre federal Old Age Security and provincial supplement for his living after he and mother followed me, their eldest son, back to Canada in 1961.

I know that I would have been able to receive a higher education, increasing my chances for a better career. To prove this to myself, I started night courses at York University in 1991, at the age of 62. Five years later, despite the fact that I was not functioning as well as I did in the makeshift high school in Lemon Creek as a teenager, I managed to graduate with a Bachelor of Administrative Studies degree. In the same month of June 1996, I became a grandfather for the first time to a child half white and half Japanese. Hopefully, the blending of races that seems to be an inevitable and rapidly increasing trend in Canada will soon make racism a thing of the past.

Traumatic experiences cannot be easily erased. Re-examining these events in my life, I find that the passage of time has not diminished my sense of outrage. I do not feel bitterness towards ordinary Canadians. During the war and for years after the war, many of them fell under the influence of hate-mongering politicians who tried to convince the nation that Japanese Canadians were enemy aliens not to be trusted. What these politicians and bureaucrats did to Japanese Canadians on the basis of our ancestry is a vile example of institutionalized racism that should never be forgotten-just like the Holocaust of the Jews in Europe should never be forgotten.

Part III: POW 348, Camp 101, Angler

By Harry Yonekura

I was 19 years old on that unforgettable day in December 1941 when my tranquil life was irrevocably changed. The bombing of Pearl Harbor was an historic event that was to affect me in ways I could never have imagined.

I had become the family breadwinner at the age of 16. My father had suffered a stroke three years earlier, and I knew from that moment that my carefree, childhood days were numbered. Sometime during the intervening years I had come to terms with the reality that while my schoolmates were out playing ball, I had to work. Accepting my fate, I made up my mind to try to become the best fisherman I could possibly be. But then the racist hysteria created by Pearl Harbor brought my fishing career to an abrupt halt, radically changing my life forever.

When news of the bombing was announced, I was busily washing my boat in preparation for winter storage. That year had been my most successful one so far. According to predictions, 1942 was going to be an even bigger and better year. As I worked on my boat, I dreamed about future catches with the new gill net boat that my boat builder friend was going to make for me. When completed, it would be the largest one of its kind on the Fraser River. As I sloshed rinse water over my boat, one of my friends came running up to me to tell me about Japan’s latest act of military aggression. I was stunned! Dropping everything, I raced home to be with my family. Because we had never been fully accepted by the dominant white society of British Columbia, I wondered what the repercussions of the bombing would be for our community. Would I ever be able to fish again?

Later on that night of December 7, 1941, I found out that my fears were well founded, as 39 Japanese nationals were picked up on suspicion of espionage. The RCMP had labelled these respected leaders of the Japanese Canadian community “fifth columnists”. Allowed to take only the bare necessities with them—a toothbrush and a change of clothes—they were whisked off to a POW camp in Alberta. This event sent waves of panic and terror through the community, especially when it was discovered that the roundup had been accomplished through the help of members of our own community who were apparently working as informants for the RCMP, secretly pointing the finger at any person in the community whom they felt had the slightest potential to become a traitor. These so-called “fifth columnists” were singled out because of their positions of power and influence in the community. They included a Buddhist minister, Japanese language schoolteachers and Japanese language newspaper editors. Mr. Tokikazu Tanaka, principal of the Queensborough Japanese Language School, was another victim in this witch hunt. All 39 were thrown into a POW camp.

The fishermen were the next group to be targeted. The day after Pearl Harbor, a group of fishermen from the Skeena River were ordered into their boats without warning—no food and no extra clothing. Their fishing boats were tied to a big naval vessel and towed for four days on the open sea to the dispersal centre. Winter had set in and the men were suffering from extreme cold and hunger. There was no stop for food or water until a day and a half into the journey when the fishermen began to complain. When these fellow JC fishermen from Skeena finally landed in Steveston, we took them home with us for a hot bath and some hot, nourishing food. When ordered back to the navy boat, none of these men obeyed. It was this incident that later influenced my decision to join the Mass Evacuation Group and so resist the cruel and unnecessary government policy of separating Japanese Canadian families.

The following day, we were notified that an Order-in-Council had been passed authorizing the impoundment of the remaining boats. We also learned that another Order-in-Council would impose a curfew on all “enemy aliens”, effective from 7:00 p.m. to 6:00 a.m. No one of Japanese origin could be seen outdoors, unless special permission was granted. As well, we were ordered to turn over all cameras, radios, automobiles and firearms to the authorities.

A Final Farewell to Our Boats

We had learned that our boats would be towed to the Annieville Dyke in New Westminster. Standing there with some other JC fishermen, watching our boats—our livelihoods—passing by en route to the dispersal centre, we realized to our horror that the boats were being damaged because they had been poorly tied together. My mind filled with memories of the care I had lavished on my boat and I could feel my heart pounding with anger and frustration.

Standing beside me to witness this travesty was Unosuke Sakamoto, President of the Fishermen’s Association, and Yoshio Kanda, a district representative of the association. The three of us decided to complain to the Commandant at Gary Point Naval Base. Reluctantly, the Commandant admitted that he had placed inexperienced men in charge of towing our fishing vessels. He also told us that he had been placed in charge of impounding all 1,137 fishing boats and his deadlthine for this mission was December 27, 1941. It was now December 14. This meant that he had only 15 days left to deliver the remaining boats. There were about 450 to 500 fishing boats to impound in Steveston alone! Tentatively, Mr.Sakamoto suggested that the Japanese Canadian fishermen be allowed to sail their own boats to the Annieville Dyke. The offer was readily accepted. There was just one hitch in the plan—how would we get back to the mainland? The Commandant did not hesitate to offer us passage back to the mainland on a naval ferry, from where we pooled our resources and paid for transportation back to Steveston.

I guess we all needed one last voyage on our own boats before bidding them farewell, possibly forever. I will never forget the overwhelming sadness and sense of disbelief I felt at Annieville Dyke as I patted my boat and tied it up securely one last time. Then I quietly said goodbye and got up, resolving to put aside my emotions and accept the situation. My country was at war and I had to do whatever was necessary to prove my loyalty.

During our last few moments with our boats, Mr. Sakamoto tried to draw an analogy between the impoundment of our boats and a death in the family. He said that we had been asked to forget our personal feelings for the sake of our country, which is what is expected when a beloved member of the family passes away and one is forced to ignore one’s feelings of grief and loss while there are funeral arrangements to be made and mourners to receive. But with those boats we had sustained our families despite ongoing attempts by the government to drive us out of the fishing industry through restrictive legislation. We learned to cope. We got used to the discrimination that we faced. But having to sacrifice our boats—the focal point of our lives—was the hardest thing of all to bear.

Now, whenever I think about my boat, my thoughts drift to my parents. During my adolescence, I probably took my parents for granted, but now I see that I couldn’t have become a successful fisherman without their continuous moral support and hard work. Every morning at 4:00 a.m., my mother would cook an entire day’s food supply for me. In those days, because of the lack of refrigeration, my mother was very careful when selecting the food for my bento (i.e., a Japanese style lunch box divided into sections). By 6:00 a.m. she delivered the bento to the packer boat responsible for District #1 where I fished. Around 10:30 or 11:00, the packer boat would drop off the still warm food. Thus, I could always count on an instant warm lunch. I didn’t have to waste precious time preparing my meals as other fishermen did. I could work hour after hour hauling in my nets and then whenever I was ready to eat, dig into my bento.

My father was also an enormous help to me. In the first year of my career he used to go out to the fishing grounds with me. At that time the nets had to be hauled up by hand since there was no mechanical retrieval system. Because of my father’s weakened condition, I was careful to position myself in front of him where I would bear the brunt of the loaded nets. But when he could no longer fish, he became my net mender. During the winter months, both my parents would hand-make some of my nets. About 12 or 13 different size meshes were used, depending on what type of salmon was running during that particular four year spawning cycle. As a result, the nets always needed mending. All of those sweet memories dissolved into the distance as I boarded the naval ferry back to the mainland.

A Woman Weeping at the Train Station

Shortly after we returned from Annieville Dyke, the government began sending Japanese nationals between the ages of 18 and 45 to road camps. Each week another trainload of them would be shipped out. A deadline of mid-March 1942 had been set for the expulsion of all native born Japanese. Many families were left without a father, without any source of income for food or other necessities. Something had to be done to help these families, so as a district representative, I helped organize a food pool. Despite the fact that we were all suffering, the community rallied to help out by donating enough money to purchase entire food stocks at wholesale prices. We also helped these fatherless families pack and organize their belongings in preparation for the ultimate moment when they too would be expelled from their homes.

Everything was happening so fast during those first few crazy months that I didn’t have time to sit down and analyze the situation. I hadn’t begun to comprehend the enormity of the injustices we were experiencing. I was too preoccupied with practical matters. Besides, our community leaders, afraid of a backlash, were preaching total cooperation with the government. They said that we should prove that Japanese Canadians are loyal, law-abiding citizens. At first, most of us did all we could do to fulfill this mandate, trying to convince ourselves that “it couldn’t be helped”.

However, one day while watching the last group of men being led to a waiting train, I witnessed a disturbing scene that will remain with me forever. An issei woman, whose husband had just entered the train, was down on her hands and knees begging an RCMP officer to take her with her husband. With an infant on her back and a tearful three year old by her side, she wept at the feet of this stone-faced officer. The tears were coursing down her cheeks. She was not asking that her husband be allowed to stay. She merely wanted to accompany him to wherever he was being taken so the family would not be split apart. Seeing this public outpouring of raw emotion, I became convinced that something was terribly wrong. How could our community leaders continue to preach conformity to government orders when faced with such inhumane treatment?

I felt that the government was perpetrating a grave injustice upon Japanese Canadians by forcibly splitting up family units and I began to share my views with my friends. A few days later, some Vancouver community leaders, including Fujikazu Tanaka, Bob Shimoda and Shigeichi Uchibori, arrived in Steveston. A meeting took place and we listened intently as the three men gave us the latest details regarding the government’s expulsion and relocation plan. By the end of the meeting, two factions had emerged. One group advocated total cooperation with the government, while the other one stood for family unification. Needless to say, I joined the latter group.

Later that night, I had trouble falling asleep. My mind kept returning to the weeping woman at the train station. I could hear her voice over and over again, desperately imploring the officer to let her get on the train with her husband. My indignation and anger overwhelmed me as I tossed and turned in my bed. I knew that I could never again blindly accept what I perceived as undemocratic and racially motivated policies.

Used to rising early, I got up as usual at 5:00 a.m., and went outside. And, as was my custom, I looked up at the sky to check the weather conditions. Slowly, I made my way down towards the river to check my boat—only this time there was no boat to check. Along with the realization that I no longer had a boat, I also confronted the fact that I did not have sufficient education, training or experience in any other field but fishing. As I stood there gazing at the river, the reality of being unemployed and unemployable hit me like a gigantic rock. As a fisherman, the weather, the high tide and low tide—indeed all that once had ruled my life—were no longer my concern. Only another fisherman would understand my emotions at the time. Even now, almost 60 years later whenever I visit B.C., those powerful emotions return, as I take yet another photo of the Fraser River at Gary Point—the river that was once my second home.

Returning home from my walk along the river that spring morning in 1942, I caught my sister and brother-in-law in a heated argument. This was very uncharacteristic of them. Therefore, I knew that the issue between them had to be pretty serious. It was soon revealed that my brother-in-law wanted to be removed to a sugar beet farm in Manitoba, but my sister did not want to venture there, despite the fact that this was the only way that they could stay together. At the same time, my parents were slated to go to Kaslo, but accommodations there were scarce. Consequently, the authorities had to issue extension papers to all proposed Kaslo internees. Meanwhile, a deadline for leaving Steveston had been set, so our family, along with many others, were forced to find temporary accommodations at Vancouver rooming houses.

Daring to Stand Up for Our Rights

Around the time of our expulsion from Steveston, tensions were developing within our own community between the JCCL leaders who advocated total compliance with government orders and the Mass Evacuation Group who wanted to keep family groups together. Finally, Fujikazu Tanaka and Bob Shimoda, two of the main proponents of mass evacuation (i.e., expulsion) were forced out of the Japanese Canadian Citizens’ League (JCCL). Strengthening their arguments was the example of the United States where close to 100,000 Japanese Americans had been allowed to go to the internment camps in family units. We could not comprehend why the Canadian government could not follow the same program when there were only 23,000 of us. Why did the government insist on separating the men from their families?

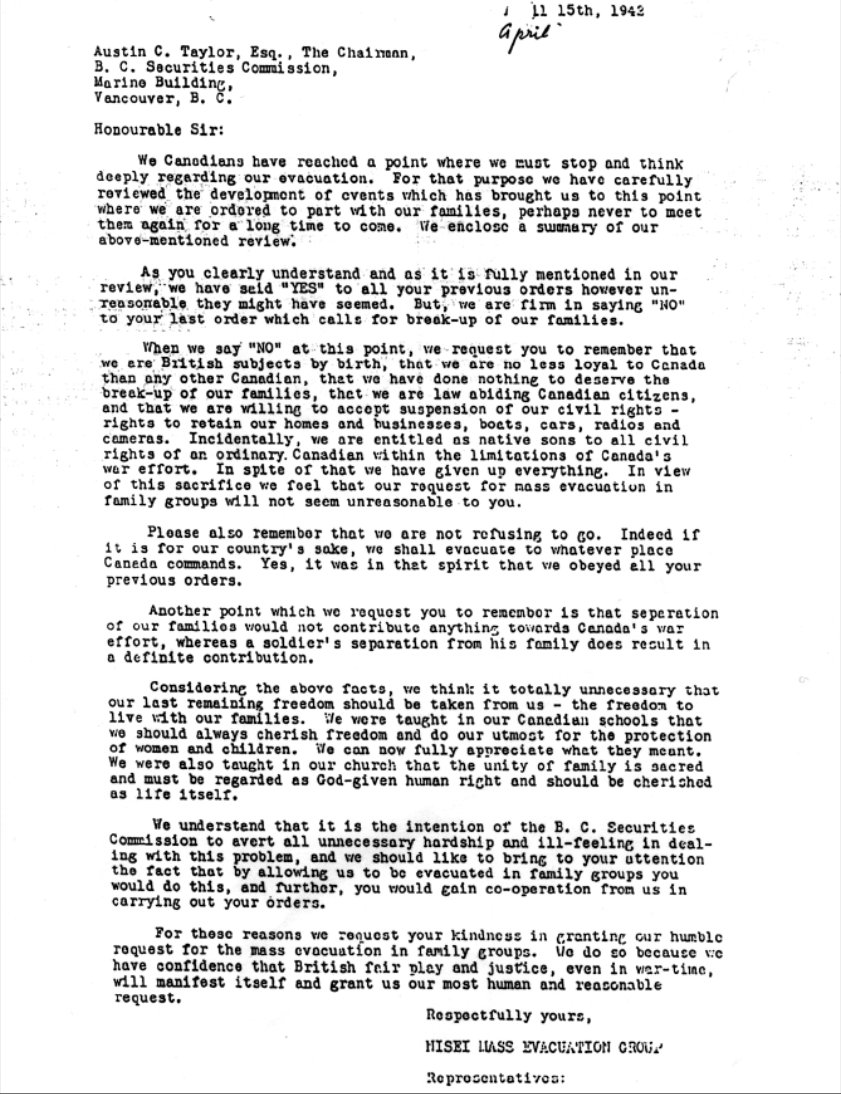

Although we were not too comfortable about confronting the Government of Canada, we felt that we had no choice but to do so. Our families meant more to us than anything else. Since our movements were restricted, those of us involved in the Mass Evacuation Group had to hire a lawyer to lobby our case in Vancouver and Ottawa. Our lawyer, Paul Murphy, met with the Minister of Labour, Humphrey Mitchell, who passed the buck to the B.C. Security Commission. As a last resort, our group sent an open letter to the B.C. Security Commissioner, Mr. Austin Taylor, stating our case for mass evacuation. We asked him to reconsider his policy of separating families on the grounds that it was cruel and inhumane and represented a disregard for basic democratic rights. As expected, Taylor would not budge. His stubborn refusal to listen to our pleas was not our only source of outrage at that time. We also had to face the blatant racism of another prominent politician, Louis St. Laurent, the minister of justice in MacKenzie King’s cabinet. When questioned by a CCF Member of Parliament about the illegality of sending Canadian citizens to POW camps, he stood up and replied, “Once a Jap, always a Jap. Blood is thicker than water.” His comments were splashed across Vancouver newspaper headlines the next day. Coupled with Taylor’s rejection of our proposal, this did more than anything so far to convince more nisei to join our Mass Evacuation movement and tear up their extension papers.

We soon discovered that all our movements were under the scrutiny of the RCMP who were searching for “subversives” around every corner. One day in mid-June, three of my friends and I decided to pay a visit to the B.C. Security Commission to make enquiries about our fate. There had been no word about where we were being sent and we felt that it was our right to know. Before we reached the commissioner’s office, we made a few stops along the way. First there was Kondo’s Drug Store on the corner of Powell Street and Main. While inside chatting with a friend, one of us noticed a known “secret agent” outside—a watchdog for the RCMP—so we decided to move on. Continuing towards the B.C. Security Commission building, we stopped again for about 40 minutes to play a few games of archery. Little did we know that this brief excursion through the streets of the neighbourhood would cost us our freedom. That 40 minutes spent in the archery arcade gave the RCMP time to coordinate our capture perfectly. Neatly sandwiched between two squad cars, one approaching from each end of Hastings Street, we were boxed in with no possible escape route.

First we were asked for our I.D. cards. After producing them, the officers asked for our extension papers. Not one of us could produce an extension paper, having previously destroyed them in anger and resentment. We were ordered into a squad car, but I had been having difficulty fitting my I.D. card back into my wallet. Therefore, I was slow to obey. One of the officers reacted by pushing me towards the car and I automatically raised my head. In that instant, I caught a quick glimpse of an Asian face ducking down behind a storefront window. At the time I thought little of it, but in retrospect, I realize that this Asian face belonged to the informant who had likely been following us and reporting to the RCMP by phone. It was the only plausible explanation for the perfect timing of our capture, especially in those days before two-way radios.

The four of us were carted off to the Immigration Jail at the foot of Burrard Street, arriving around 11:00 a.m. This bleak place already held about 150 JC detainees, all of whom were confined in a space originally intended to house about 20 temporary immigrants. There were no beds, only a blanket and a thin mattress laid out on the cold, concrete floor. Even though this was the fourth floor of the building, it looked and smelled like a dungeon—a grim reminder of our dismal plight.

My first concern was to contact my mother to let her know where I was, but when I asked the guard if I could use the phone, he completely ignored me. Around 11:45 a.m. a Chinese kitchen worker delivered our lunch. I again asked if I could make a phone call. It was not permitted. When I was almost finished my lunch, my fellow inmates told me to hang onto my cutlery, as I would need it. I was puzzled. Later I was told that if I wanted to get a message to my family, I would need to send it via one of the visitors gathered outside of the jail each day hoping to catch a glimpse of their loved ones. Visitors were kept back and away from the jail a distance of about half a block, so it was necessary to weight down a message with the cutlery in order to have it cross the stretch separating us from the visitors.

That afternoon I made my first attempt. With a snap of my wrist, I sent my note soaring through the barred window towards the waiting crowd. To my chagrin, my missile fell far short of its mark. However, one remarkably determined woman, braving the stern warning of a jail guard, ran forward into the restricted zone and snatched up my note, waving it in the air to show that she had it. The note contained my name and the names of my three buddies, along with my mother’s address. Luckily, the note got through to the Mass Evacuation headquarters at the Patricia Hotel on Hastings from where it was delivered to my mother. Two days later my mother and sister came to visit, bringing my already packed bags from the rooming house where we lived. For the past three days while in jail, I had not even been able to brush my teeth! Years later, my mother told me she set out my dinner plate two nights running, and when I failed to turn up, she concluded that I had been picked up by the RCMP and thrown into jail.

During the first week of July 1942, Mr. Shigeichi Uchibori visited us in jail to update us on the results of his negotiations with the government. We were relieved to learn that our two most important requests had been granted. The B.C. Security Commission had accepted the mass evacuation policy, provided that our organization cease all underground activity. The government also agreed to guarantee food and shelter for all JC evacuees, moving them out of the Hastings Park grounds to camps in the Slocan Valley and Tashme areas.

Mr. Uchibori did not succeed in getting the release of the men in the POW camps of Angler and Petawawa. Nor could he secure the release of any JC inmates at the Immigration Jail—even after he suggested that they be used as labourers to build the shacks for the relocation camps. The government responded by sending the “road camp” JCs to build the shacks since they were viewed as “the good guys” for their complete obedience. We, on the other hand, were the “bad guys” because we had insisted upon standing up for our human rights as Canadian citizens. In those days, the notion of “human rights” was a fairly new concept. The Mass Evacuation Group was one of the first organizations to use this phrase.

Having gained our two main objectives, Mr. Uchibori asked us to formally accept the latest concessions. He advised us to write a letter of appeal to Commissioner Mead of the RCMP accepting the terms of the new policy of mass evacuation. As a member of the Mass Evacuation Group, I composed the letter, but it had to be signed by my fellow JC inmates as well. Out of 150 inmates, only 70 signed the letter. Here I learned a lesson in politics. If only 70 inmates signed the appeal, then we represented the minority. I reasoned that the majority who had not signed were single men with no family members here in Canada. It was understandable that the issue of family unity would not have as much significance to them as it did for those of us with families here.

From One Prison to Another

Ten days later we were all shipped off to Angler POW Camp “101” in Northern Ontario. Compared to life in the overcrowded Immigration Jail, Angler brought us a certain measure of “comfort”. The initial fear and hopelessness—evoked by the barbed wire and the mandatory uniforms with the huge red circle on our backs—eventually dissipated as the daily routine of prison life took over. We were assigned huts with real beds and JC community leaders were in charge of settling disputes and of general camp guidance.

I was assigned to Hut 3B where many of my roommates were comprised of Mass Evacuation Group executives and their supporters. I was surprised to learn from them that the RCMP had raided our Mass Evacuation headquarters at the Patricia Hotel during a meeting. Mr. Uchibori had escaped arrest only because he was half an hour late arriving and missed the whole thing. Some of the other men in my hut were strangers to me. Three beds to the right of mine, there was a kika nisei (Japan educated nisei) who had been arrested for a curfew violation. This man had lived in an all-white neighbourhood and had had very little contact with other Japanese Canadians. In fact, he had not even been aware of the curfew. Both his parents were dead and his only living relative was a sister he had been forced to leave behind. He worried about her constantly and eventually developed signs of mental illness. His entire body would begin to shake whenever he was agitated and his deeply scratched face mirrored a tortured soul. Eventually, he was sent to a mental institution in Winnipeg.

Thinking about this lonely man in my hut only augmented my own feelings of depression. I felt so closed in for I had spent most of my recent years on the endless expanse of the open sea. My sense of confinement therefore was very acute. It was now November 1942, and I knew that I had to pull myself together if I was not to end up as another JC patient in a mental institution. So I asked my hut leader to try to arrange a job transfer for me. I had been working in the postal sorting centre for two months and then in the claustrophobic camp kitchen, serving meals to the other inmates. I asked to be transferred to the “clean-up crew” who were responsible for maintaining the grounds around the prison compound. Working six hours a day outside soon began to restore my natural good spirits. At the same time, I had recently renewed and reinforced my faith in the Buddhist beliefs I had grown up with. This gave me the strength to deal with the feelings of apprehension that had been building up inside me all these months.

Around this time, Mr. Fujikazu Tanaka received a report from Mr. Shigeichi Uchibori advising that about 95% of the remaining evacuees were now safely settled in the facilities constructed for them. A few families had absolutely refused to leave their homes in Vancouver, stating that as Canadian citizens they had every right to remain in the city. These people were still in Vancouver after the last of the evacuees had left.

After hearing Mr. Uchibori’s report, the Mass Evacuation leaders met and then disbanded as a group. We were now able to contemplate what course to choose for our individual futures. There were, at the time, two schools of thought regarding the future. A group of kika nisei advocated denouncing their Canadian citizenship so they could be included in the government’s exchange plan for VIPs stranded in Japan. These were the Canadian consuls and/or ambassadors and their staff who had been caught in Japan when the war broke out. The kika nisei still had fairly strong ties to Japan, and resented the treatment they were experiencing from the Canadian government.

Before 1942 came to a close, I took the step of requesting a formal hearing for my release from the camp. My hearing was held during the last week of January 1943. Commander Bradshaw, a very tall man whose voice held a ring of authority, presided over my hearing. I was accompanied by Tokikazu Tanaka, camp leader. Also present was and Mr. Pipher, the head of the B.C. Security Commission, Eastern Region. When Commander Bradshaw entered the room, followed by four officers, everyone stood up. When he sat down, everyone sat down. I remember feeling extremely nervous, but Mr. Tanaka reassured me that everything was fine. And then suddenly, Commander Bradshaw’s booming voice barked at me, “What makes you think you should be released from here?” Momentarily startled, but determined to have my say, I stood up and replied, “Sir, in my religion, giving is the most important part of my belief. This past Christmas I received two gifts from my family, but because I was confined in Angler POW Camp 101, I was unable to give them a gift in return. Because of that, I had a very unhappy and lonely Christmas. By Christmas 1943, if I receive two gifts, I want to be in a position to give back four.” Commander Bradshaw pointed his finger at me and in his booming voice uttered two condescending words, “Good boy!” Then he left the room. I was a free man!

For the first time since my boat was confiscated, I could begin to plan for my future. Mr. Pipher informed me that there was a good job in Toronto, but I was not used to large cities. Eventually, I opted for the Pigeon Timber Company in Neys, Ontario. When May arrived, I began working there, thus starting a new chapter in my life.

HASTINGS PARK (now the site of the Pacific National Exhibition) served as the emergency dispersal centre for Japanese Canadians who were driven from their homes. Yuki Mizuyabu was among the many Japanese Canadians imprisoned at Hastings Park.

Needless to say, there was no privacy at Hastings Park. The males were forced to sleep on crude bunk beds with straw mattresses. These beds were organized in monotonous rows, reinforcing the feeling of degradation since they were placed in a building usually used to house livestock. (Photo courtesy Vancouver Public Library)

Hastings Park racetrack was where the Japanese Canadians were forced to take their cars and trucks. The office of the Secretary of State appointed a custodian to auction off these vehicles as quickly as possible. (Photo courtesy Special Collections: UBC Library)

Japanese Canadians lining up for the rations of food at Hastings Park. Sometimes inadequate food preparation and storage was a problem resulting in outbreaks of diarrhea. (Photo courtesy Vancouver Public Library)

Daily life at Hastings Park was boring and claustrophobic for the women and children. (Photo courtesy Vancouver Public Library)

Dorothy Kagawa (nee Okuma) with her grade one to four class standing in front of the East Lillooet School, District 29, circa late 1940s. Stan Hiraki was also a teacher at the school in charge of the upper grades. (Photo courtesy Dorothy Kagawa)

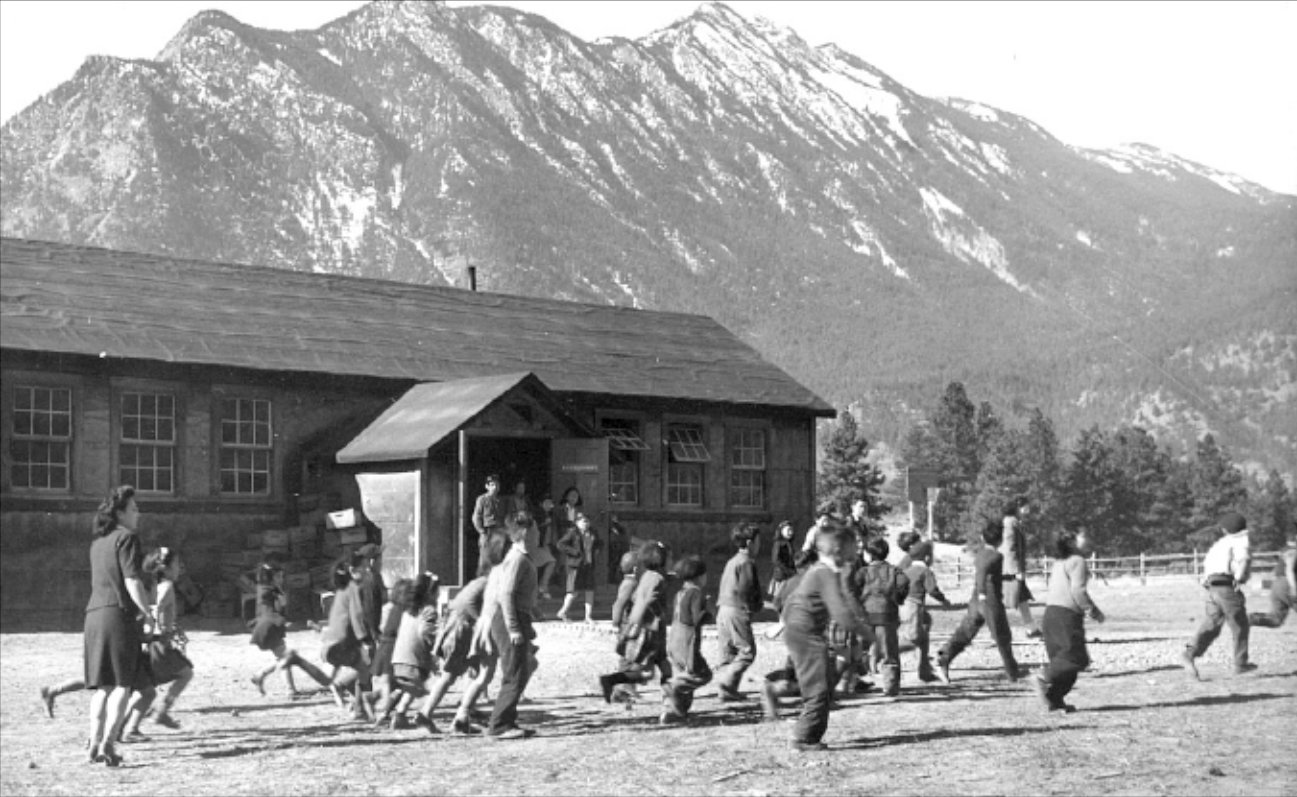

Dorothy Kagawa and her multi-level class at recess time. This building, which served as both a school and community centre, was built by the Japanese Canadians in this self supporting community. (Photo courtesy Dorothy Kagawa)

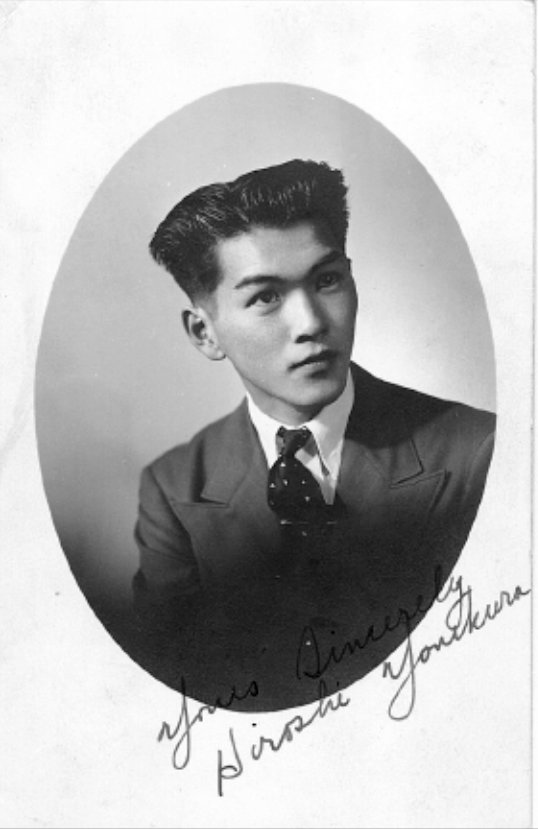

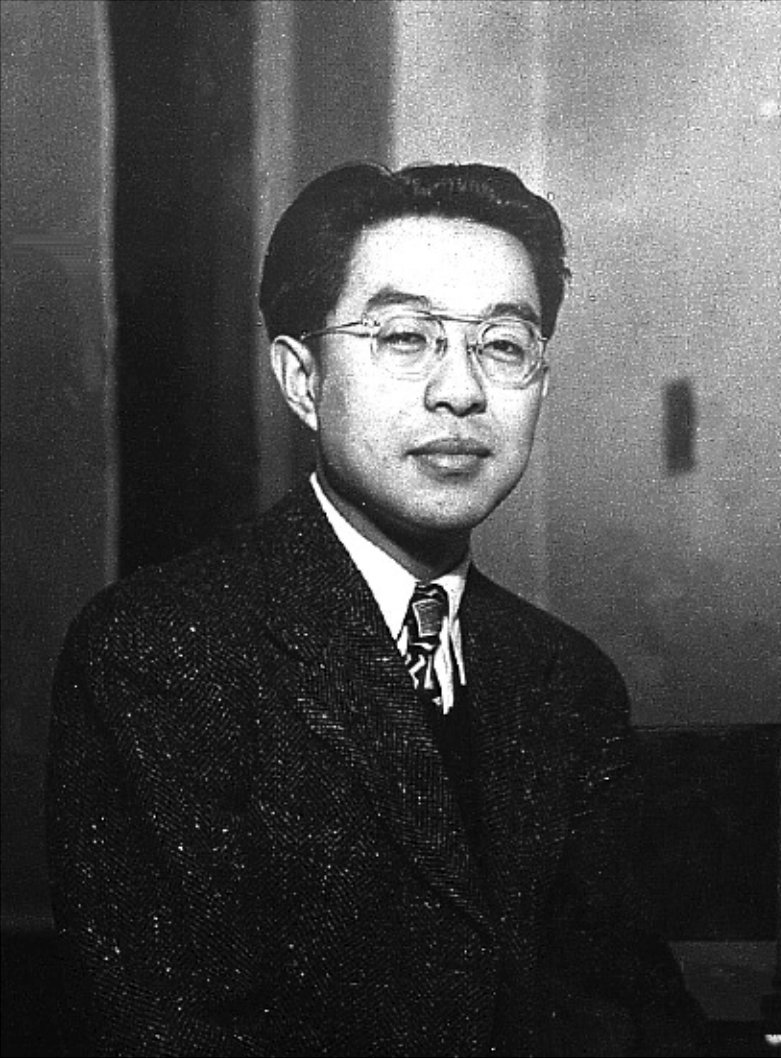

Stan Hiraki at 29. (Photo courtesy Stan Hiraki)

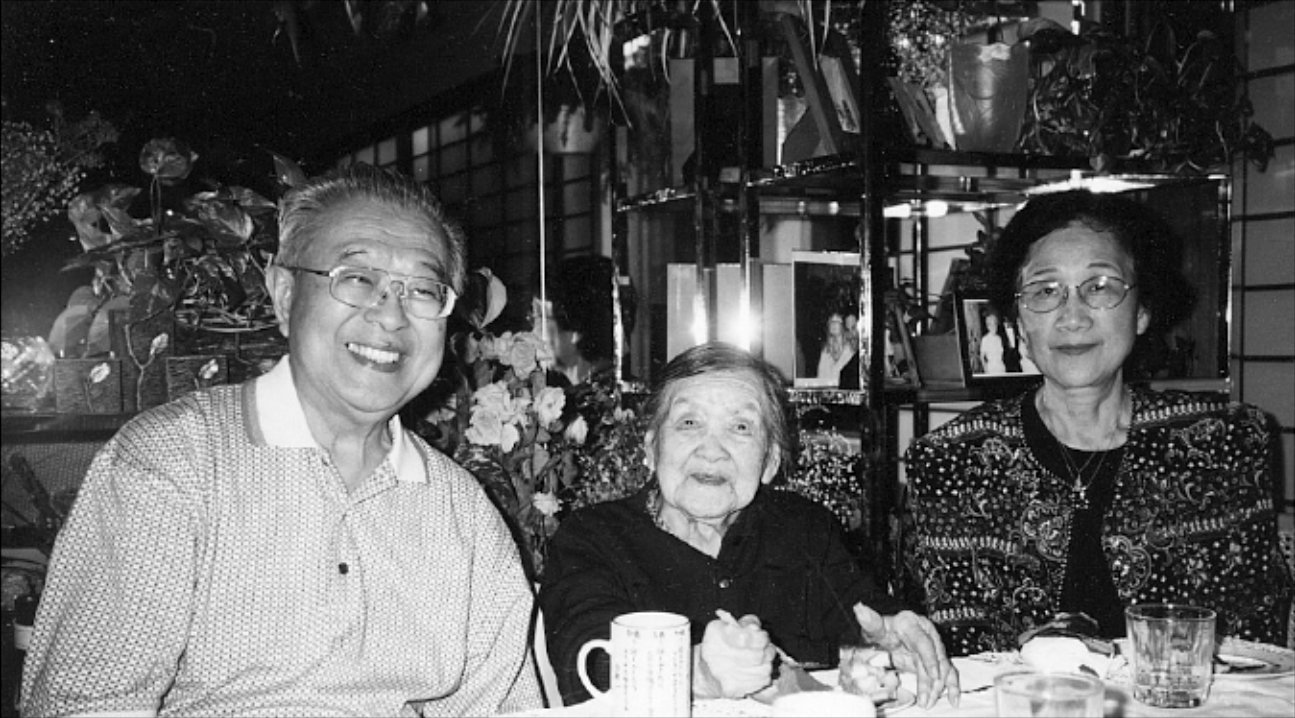

Stan Hiraki with his 106 year old mother, Sawa Hiraki, and his wife, Marjorie Hiraki, in October 1999. (Photo courtesy Stan Hiraki)

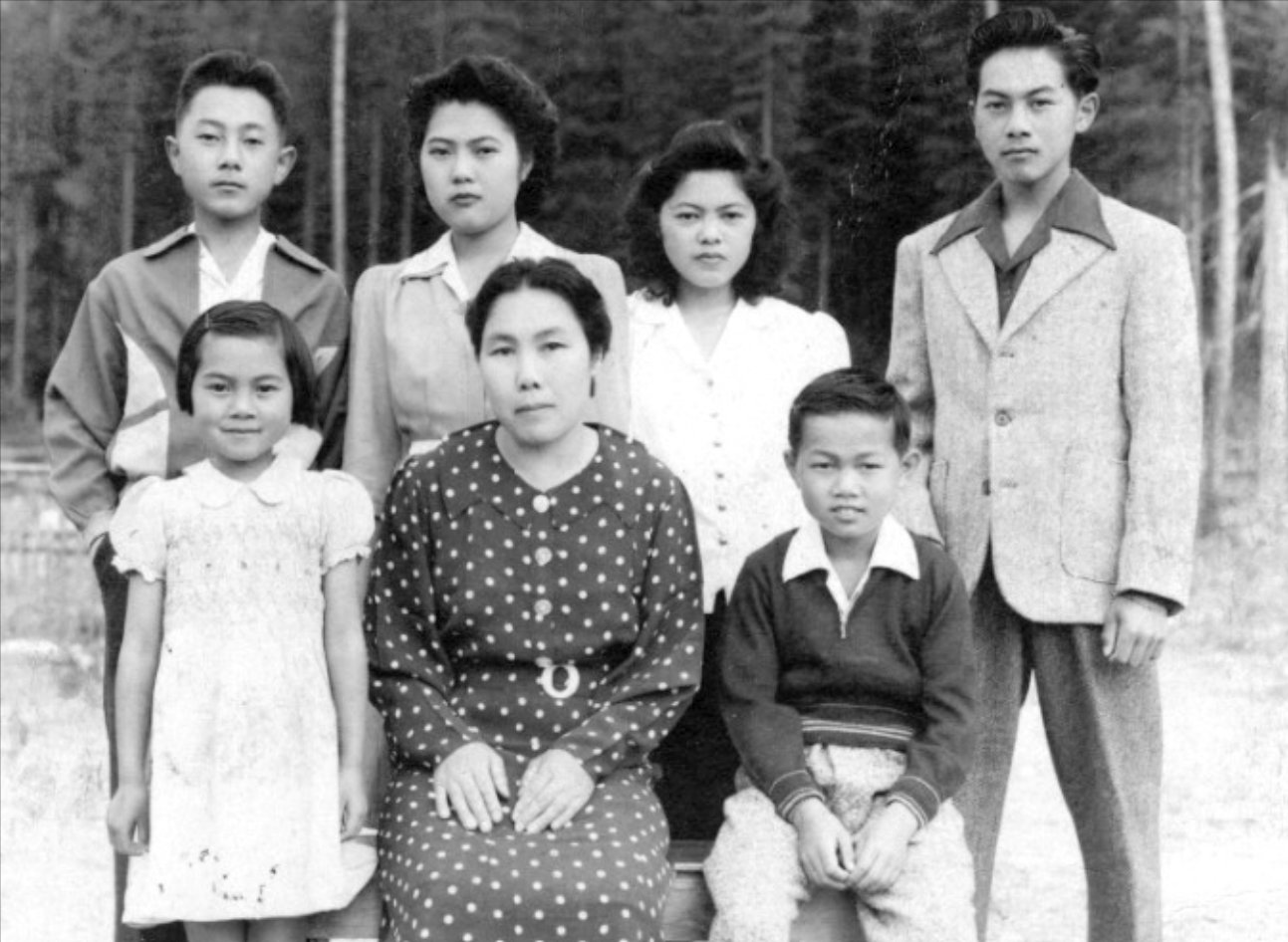

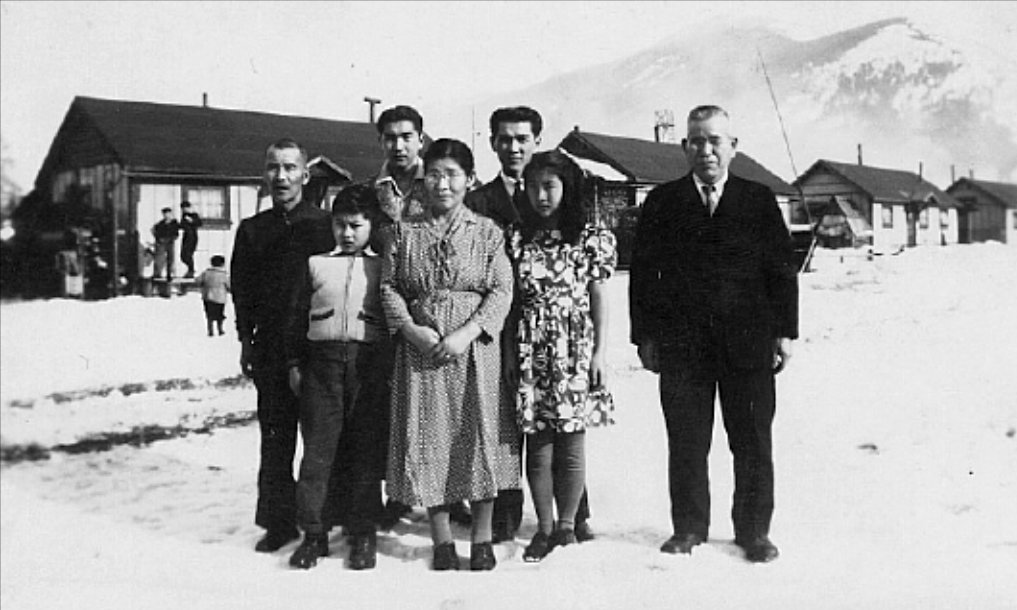

Yuki (far right) with his mother and five siblings in Lemon Creek, May 1946. (Photo: J.T. Izumi)

The Mizuyabu home at 238 Chelsea Street in Nanaimo. Yuki’s father had this house built on a double lot just a year before they were forced to leave it. (Photo courtesy Yuki Mizuyabu)

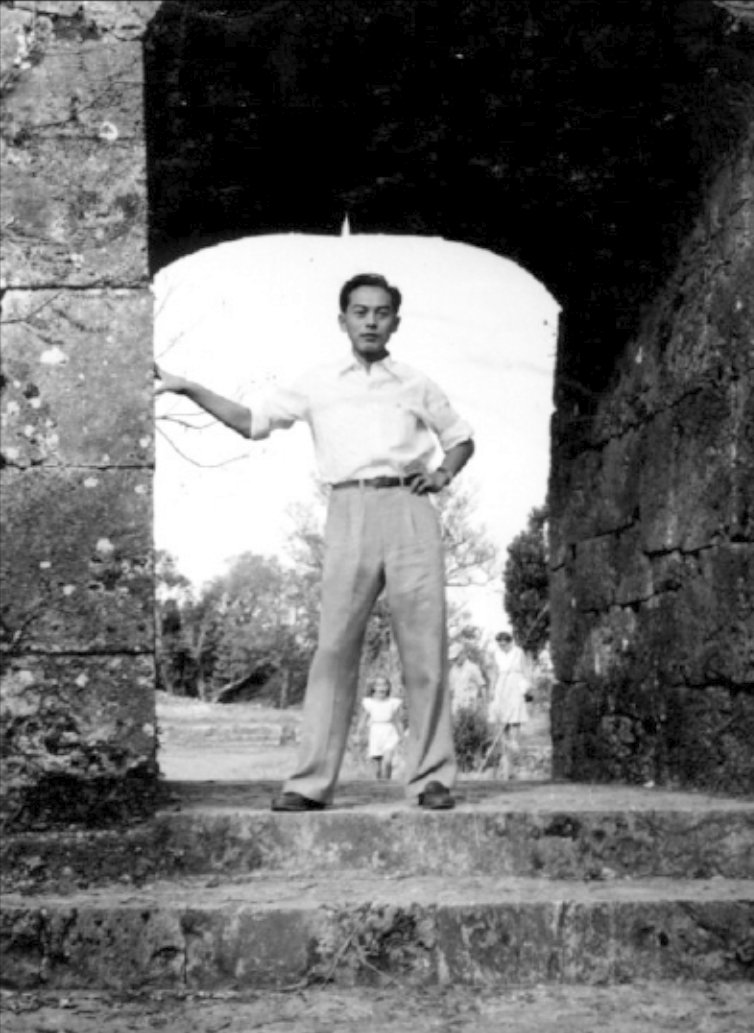

Yuki at the ruins of Nakagusuku Castle in Okinawa, fall of 1953. Yuki spent most of the 1950s in Okinawa working with the American military as an interpreter. (Photo courtesy Yuki Mizuyabu)

Yuki visiting Osaka, Japan, 1956. (Photo courtesy Yuki Mizuyabu)

Yuki’s first Canadian passport after his application for “clarification of Canadian citizenship" was accepted. He used it to return to Canada in 1961. (Photo Courtesy Yuki Mizuyabu)

Yuki at his graduation, York University, 1996, where he received a Bachelor of Administrative Studies degree. (Photo courtesy Yuki Mizuyabu)

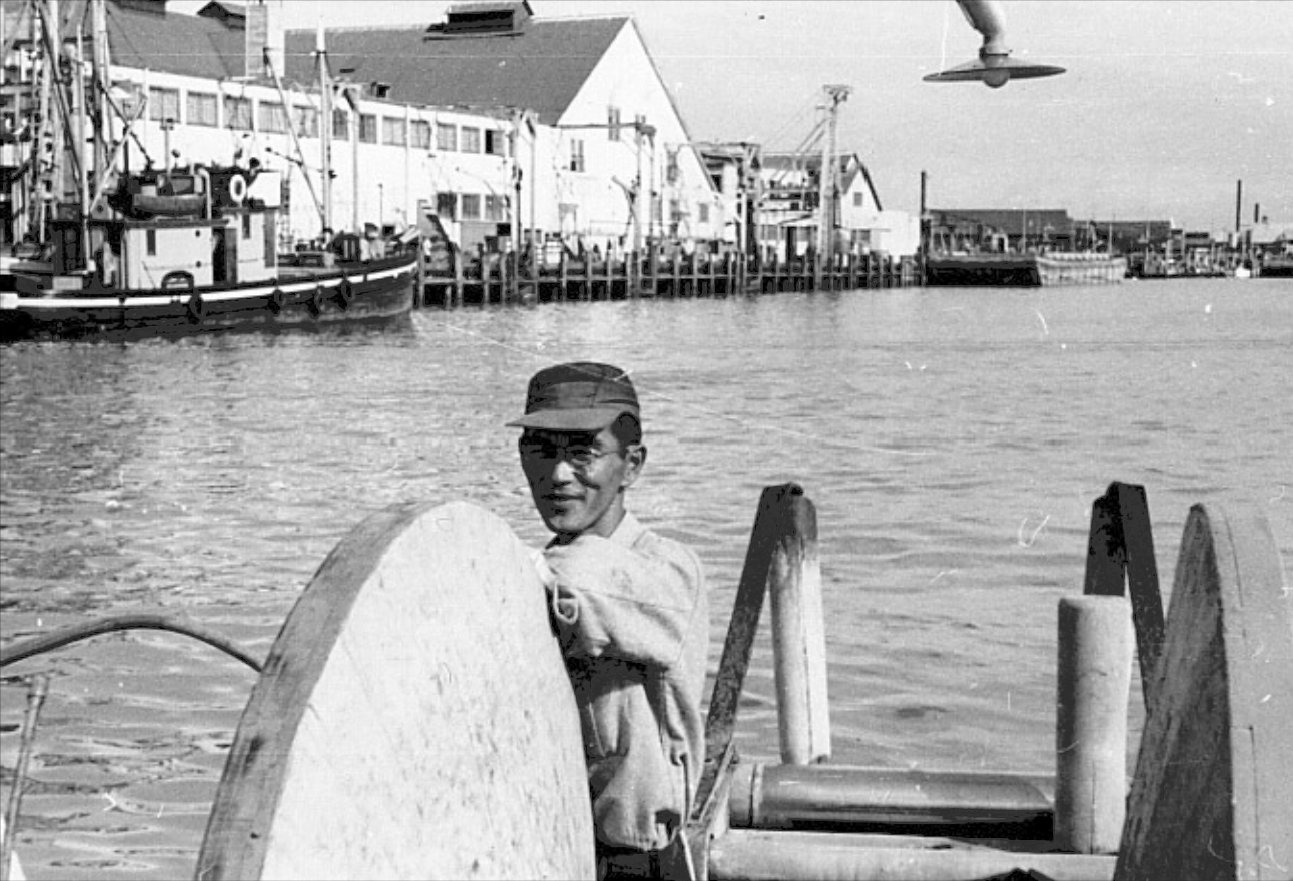

A young Harry Yonekura and his fishing boat. (Photo courtesy Harry Yonekura)

About 1,000 Japanese Canadian owned fishing boats were impounded by the government and taken to Annieville Dyke. They were later sold for next to nothing by the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property. (Photo courtesy Special Collections, UBC Library)

One of the tragedies of the expulsion is that many families were forced to separate. Women and children went to detention camps in the B.C. interior while some of the male members of the family were taken to road camps. This photo shows Japanese Canadians during the confusion of relocation to the Slocan area. In the spring of 1942, Harry Yonekura became involved in the Mass Evacuation Group, a lobbying organization that tried to keep families together. (Photo: Tak Toyota/National Archives of Canada)

The Yonekura family in Lemon Creek, 1944. Left to right: Tomekichi (father), Yoshiharu (brother), Tadao (brother), Sumiye (mother), Harry, Asako (sister), Toramatsu Ito (uncle). (Photo courtesy Harry Yonekura)

The letter above to the B.C. Security Commission from the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group provided logical arguments for keeping families together.

Angler, Ontario, P.O.W. Camp where Harry Yonekura was imprisoned, 1942 to 1943. In September 1995, Harry received a letter from Herb Gray, the Solicitor General at the time, assuring him that his “internment under the War Measures Act did not result from a criminal offence and, therefore, no criminal record would have been created in respect of that interment.” (Photo courtesy Archives of Ontario)