Chapter 14

Justice At Last!

By Roger Obata

When NAJC president, Art Miki, received a telephone call on August 24, 1988, from the office of the Minister of State for Multiculturalism and Citizenship, he was told to bring an extra shirt. Somehow he sensed that the meeting, to be held the following day at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Montreal, was going to be somewhat different from the previous negotiating sessions with the federal government. When he passed this information on to the rest of the NAJC Strategy Committee, I suspected that this meeting was going to be something very special.

When he entered the conference room at the Ritz Carlton, Miki came face to face with five representatives from the government: Gerry Weiner, Minister of State for Multiculturalism, Dennison Moore, Weiner’s chief of staff; Alaine Bisson, a lawyer from the Department of Justice; Anne Scotton, a multiculturalism officer and Rick Clippendale, one of Weiner’s advisors.

Along with Art Miki, six other representatives of the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) were present at the Ritz Carlton on the morning of August 25, 1988: Cassandra Kobayashi, Audrey Kobayashi, Roy Miki, Maryka Omatsu, Don Rosenbloom (the NAJC legal advisor)—and me.

Bouchard Enters the Scene

On the morning of August 25, 1988, while the two parties were making their formal introductions around the table, in walked Lucien Bouchard. Bouchard, an old classmate of Mulroney’s at Laval University, was someone who exercised considerable influence in the Cabinet. His presence in the room told me that this was “it”.

Bouchard expressed a desire to see the Redress issue resolved by the end of the meeting. He said that the $25,000 individual compensation requested by the NAJC was exorbitant. When asked what he considered a reasonable amount, he replied $15,000. Shortly after making the suggestion, Bouchard made his exit, promising to be available for consultation at any time during the negotiations.

Later that day the NAJC delegation held a separate meeting before responding to Bouchard’s unacceptable proposal of $15,000. The government team did likewise. I argued that a compromise between $15,000 and $25,000 would be $20,000—the amount that was offered to our Japanese American counterparts. I reasoned that since the Japanese Canadians suffered greater hardships and economic losses than the Japanese Americans, the NAJC should ask for another $1,000 on top of the $20,000 sum. After lengthy discussion on the matter, the Strategy Committee accepted my logic and we returned to the negotiating table, determined not to back down on our figure of $21,000.

Surprisingly, the government team did not argue very strenuously against our proposal. After a number of phone calls, presumably to Bouchard and/or Mulroney, they agreed to our figure of $21,000. The affirmative response was an enormous breakthrough! It all happened so swiftly that it took a while for the reality of it to sink in. It felt like we were in a dream. We could hardly contain our elation and shock. After facing four years of frustrating intransigence, the government’s easygoing attitude that day was difficult to comprehend. Brian Mulroney’s representatives seemed to bend over backwards to satisfy NAJC proposals. What had suddenly changed the government’s attitude towards Redress? Was it the influence of Lucien Bouchard? Was it the upcoming federal election? Or was it President Reagan’s signing of the Civil Liberties Bill on August 10, 1988?

The NAJC team did not have much time to ponder the reasons behind the sudden change of heart. There were more important and urgent issues to resolve—criteria for eligibility for individual compensation, the community fund, processing claims, the Canadian Race Relations Foundation and the implementation of the Redress Agreement. After a 17-hour marathon session, the long-awaited agreement was signed on August 26, 1988.

The most significant thing about this historic negotiating meeting was that the government was so different in its attitude towards the Redress issue. They seemed to be overly obliging in trying to meet our requests when for the past four years they had given us such a rough time during the negotiating sessions. When the meeting had concluded, we left Montreal happy with the results and wondering what had changed the government’s attitude, but perhaps we will never know. In two days of intense negotiations we had finally reached the end of a Redress campaign that we had begun in September 1947. It took us 41 years, but the victory was worth it for it restored our dignity and pride.

Keeping Our Lips Sealed

One of the most frustrating challenges facing us after our marathon session with the government negotiators was keeping the contents of the Agreement a secret for a month. We were warned not to disclose the Agreement to anyone until Prime Minister Mulroney formally announced it in the House of Commons. If there were any leaks it could jeopardize the whole settlement—so we were told. There was a possibility that World War II veterans—who could not see any distinction between Japanese Canadian citizens and Japanese soldiers—might launch a public protest against the whole idea of compensation, thus creating another hurdle for us. But, can you imagine how difficult it was for the members of the Strategy Committee to keep their lips sealed when they were bursting with anticipation to tell all their supporters the wonderful news? Various NAJC members suspected that something significant was brewing, but we maintained our promise of confidentiality. I did not even tell my wife, Mary, until September 22, 1988, when we flew back from Ottawa and arrived with Mr. Weiner at the Sutton Place Hotel in Toronto for the official announcement to the Japanese community.

The joyous celebration at the Sutton Place is a separate story that comes later. The most important event of September 22nd was the announcement of the Redress Settlement by Prime Minister Mulroney. As I recall it, the announcement was to be made at 11:00 a.m. Only four MPs—Brian Mulroney, Gerry Weiner, Lucien Bouchard and Don Mazankowski—knew the exact terms of the Redress Agreement so everyone was waiting anxiously for Mulroney to begin speaking. Those of us in the NAJC who were invited to witness this historic occasion were in the public gallery of the House of Commons. Joining me were people such as Harold Hirose, Bill Kobayashi and Mas Takahashi. Before a hushed and anxious audience, Mr. Mulroney rose from his seat and began to read the Acknowledgment and the Redress Settlement. When he had concluded there was a standing ovation.

An even more dramatic moment came when NDP leader Ed Broadbent got up to add his comments. As he quoted a passage from Joy Kogawa’s novel, Obasan, his emotion-filled voice faltered and hesitated for a brief moment. At that point I would dare to say that there were many tear-filled eyes among the Japanese Canadians in the gallery.

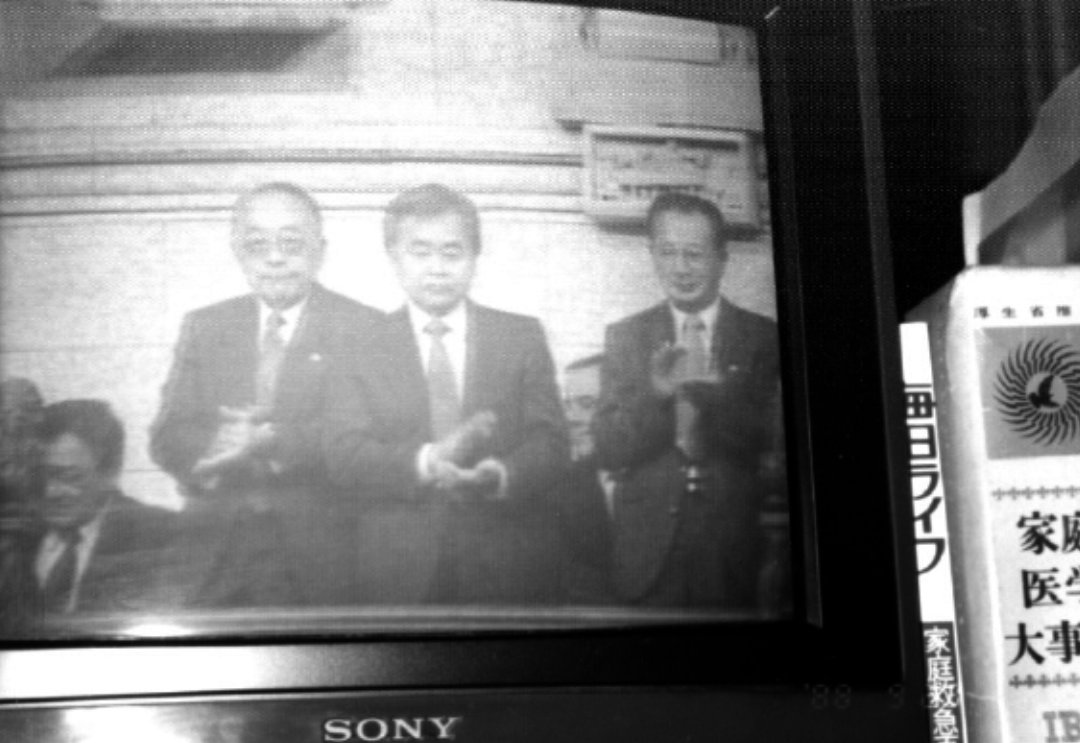

Later I found out that a close friend of mine in Tokyo, who happened to be watching television at the right time, saw on his TV screen a shot of Harold Hirose, Bill Kobayashi and me in the gallery! He happened to have his camera handy and immediately took a picture of his TV screen and sent it to me. Since no cameras are allowed in the House, this photo is a rare memento of that historic day, and one that I will always treasure.

For me personally, it is difficult to describe the feeling that welled up within me as I stood and applauded Mr. Mulroney from the gallery. I felt that a tremendous load had been lifted when the label of “enemy alien” was official removed from my back with the prime minister’s apology on behalf of the Canadian government.

It was an unforgettable, emotional moment for Japanese Canadians watching from the visitors’ gallery. After 41 long years, I suddenly felt ten feet tall! The Government of Canada was finally acknowledging that what they did to us during and after the war was “unjust”. Our forced removal and internment, our deportation and expulsion, the confiscation and sale of our private and community property, the restriction of our movement and our disenfranchisement were now considered to be influenced by “discriminatory attitudes”—not threats to national security. The official “Acknowledgement” even noted the fact that the proceeds of the liquidation of our property were used to pay for our own internment!

An official signing of the Agreement by Art Miki followed the announcement and other speeches in the House of Commons. Then a press conference was held at the National Press Gallery where Gerry Weiner and Art Miki appeared before a sea of reporters. The significance of this historic event was evident from the extensive media coverage. Following the press conference, we attended a reception in the Centre Block of the House of Commons. It was an opportunity for NAJC representatives to thank the politicians who had supported our cause during the five-year Redress campaign—John Turner, Ed Broadbent, Sergio Marchi, Ernie Epp, Dan Heap, John Fraser and Gerry Weiner. They in turn congratulated us for our successful perseverance. Mr. Weiner publicly invited the NAJC members present at this reception to another reception later that day at the Sutton Place Hotel in Toronto.

The Agreement became front-page news. There was pandemonium in every Japanese community across Canada. Phones were ringing off the hook as the media tried to contact people in our community to get a reaction to this announcement. In Winnipeg, Mrs. Miki, mother of Art and Roy Miki, was interviewed on television. Apparently, she cried for joy knowing how much effort her sons had contributed towards the victory. All across the country Japanese Canadians celebrated. We did it. We finally did it!

We were caught up in a euphoric flurry of activity as we dashed from one reception to another. Bill Kobayashi, Roy Miki and I were invited to travel on the same plane as Mr. Weiner from Ottawa to Toronto to attend the government-sponsored reception at the Sutton Place Hotel that afternoon. Since those of us from the NAJC who were in Ottawa on September 22, 1988 were too overwhelmed to focus on much else other than our victory, we knew nothing about the reception in Toronto until Mr. Weiner told us about it. Spontaneously, he invited us to join him on the plane to Toronto. It was an offer we gladly accepted.

Sutton Place Ballroom

An air of exhilaration and joy filled the ballroom of the Sutton Place Hotel on the afternoon of September 22, 1988. The Japanese Canadians of Metropolitan Toronto had been invited by the Secretary of State to hear an important announcement. By that time, of course, most Japanese Canadians had heard some sort of settlement had been reached, but they needed to hear the official details from the mouth of Gerry Weiner.

While servers circulated with trays of wine and hors d’oeuvres, we waited for Mr. Weiner’s arrival at the podium. While we waited, Aiko Murakami brought to my attention an upsetting sight. There displayed for everyone to see was the flag of Japan side by side with the flag of Canada. Soon every Japanese Canadian in the room became painfully aware of the presence of a familiar red circle on a white background. It was unbelievable that even on this historic occasion, Canadians of Japanese ancestry were still being associated with the national emblem of Japan. Sadly, the Canadian government could still not recognize the difference between ethnicity and nationality. After all we had just been through to reclaim our dignity, someone was again humiliating us. We were not certain who was responsible for the flag display, someone from the government or someone from the hotel. Fortunately, before the flag incident could put a permanent damper on our celebration, I managed to find Mr. Nichols of the Secretary of State to explain the total inappropriateness of displaying the Japanese flag at our celebration. He had it removed immediately.

When Mr. Weiner appeared, the formal proceedings began. He read the Acknowledgement and terms of the Redress Agreement that had been signed that morning in Ottawa by Brian Mulroney and Art Miki. A stunned audience hung on every word. Tears of joy could be seen streaming down many faces in the room. Finally, we were being recognized as full and equal citizens of Canada. The long struggle for justice was over and the healing could begin. Perhaps the most meaningful point in Mr. Weiner’s address was the admission that the actions of the Government of Canada were unjustified and discriminatory:

The Canadian government of the time committed unfair, discriminatory acts against loyal Canadians. This government is now acknowledging those wrongs and promising that they must never happen again…

We are prepared to confront prejudice or discrimination or racism—and call them unacceptable.

Our society of today would not tolerate what took place 40 years ago. We, as Canadians, have indeed changed and grown. We have acquired new wisdom and compassion. And, over the years, we have recognized the reality and the vast potential of our multicultural identity.

This government’s official acknowledgement of the injustices done to Japanese Canadians serves notice to all Canadians that the excesses of the past are condemned and that the principles of justice and equality in Canada are reaffirmed.1

Some of the Japanese Canadians in the room were too stunned to cry. There were three groups of people present at the Sutton Place that day: the jubilant NAJC supporters, the unbelieving fence sitters—and embarrassed opponents of individual compensation. Although quite a few of the naysayers were present, issei Sumie Watanabe was the only one from George Imai’s Survivors’ Group to admit misjudgment. Watanabe graciously shook hands with NAJC officials and congratulated us on the success of our negotiations.

In a bizarre twist shortly after the Sutton Place announcement, George Imai, one of the founders of the Survivors’ Group, told the press that his group had been working on “the Agreement" all along.

Public Information Meetings

As anticipated, the Toronto NAJC phone lines were jammed with calls. Toronto area Japanese Canadians had suddenly discovered our phone number. It was time for us to arrange a public meeting to give members of our community some basic information about how to apply for their compensation. It would be necessary to explain the details of the settlement and to answer the numerous questions pertaining to it.

The first meeting took place at Lawrence Park Collegiate on October 12, 1988. Scheduled to start at 7:30, the place was packed by 7:00. Hundreds of people had to be turned away as they were approaching the school. It was estimated that with standing room only, the capacity of the room was 1,000 people! Such a huge attendance had never been seen before or since at any gathering of Japanese Canadians.

In the hall leading to the auditorium, registration tables had been set up to record pertinent information about the applicants, as well as to receive memberships in the NAJC. The unprecedented turnout that night almost caused a riot to break out. People were frantically waving $20 bills for membership, believing for some strange reason that NAJC membership was a prerequisite for individual compensation. NAJC member Harry Yonekura was in charge of the membership tables that night. He recalls being afraid that the anxious crowd jamming the corridors would accidentally crush the young women working at the tables. Matt Matsui, who was also manning the tables for registering the names, said that the NAJC should have charged everyone who registered a fee for the NAJC treasury, but this idea was rejected.

For four years there had been relatively little interest in the work of the NAJC. However, that night at Lawrence Park Collegiate, Japanese Canadians were coming at us from every direction. It was a real eyeopener. Suddenly, the Japanese Canadians had found the organization that had worked long and hard for them for many years. This sudden interest seemed somewhat opportunistic and hypocritical to some NAJC executive members. One of our members found it a little too hard to take. When she saw the almost vulture-like throng, she spontaneously whispered to me, “I think I’m going to throw up!”

I shared the podium at Lawrence Park Collegiate with Shirley Yamada, Maryka Omatsu, Tomoko Makabe (translator) and Bill Kobayashi. A huge banner, which read “NAJC WINS REDRESS”, hung at the back of the stage. There was no doubt as to who had worked so hard to achieve this victory of human rights. Considerable time was spent explaining the monetary issues in the Agreement: the $21,000 individual compensation, the $12 million community fund and the $12 million contribution to the Canadian Race Relations Foundation. Then it was my turn. As the vice-president of the NAJC and senior member of the Strategy Committee, I was able to provide the history of Redress going back 41 years to the formation of the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA). I explained that one of the main purposes for its formation was the settlement of property claims arising from the expulsion. I then traced the similar developments in the Japanese American Redress campaign and described the details of our negotiations that culminated in a breakthrough on August 26, 1988.

Looking out into the sea of faces, I explained that the achievement of Redress was “an historic victory in the struggle for justice and human rights for all Canadians and not just for Japanese Canadians.” Now that the Redress issue was successfully resolved, I asked that past differences and animosities within our community be swept aside so that we could all share in the joy of reaching this historic agreement. I invited the community to unite to celebrate the Redress Agreement in the same spirit as the 1977 Japanese Canadian Centennial celebrations.

During the question and answer period of the evening, many questions were raised about the eligibility criteria. We had to state that the government had not yet confirmed these criteria. Tomoko Makabe did an excellent job of translating for the non-English speaking members of the audience who had many questions in Japanese.

The meeting at Lawrence Park turned out to be one of the largest public information meetings ever held in Toronto with an attendance of around 1,000.

Brockton High School Meeting

Because so many people had been turned away from the Lawrence Park meeting, a second information meeting was held at Brockton High School in the Bloor and Dufferin area of Toronto’s west end on October 21, 1988. There was a high demand for information and it was the responsibility of the NAJC to get the information out there. The attendance at the second meeting was much less than at the Lawrence Park. Following the Brockton High School meeting, the Redress implementation program was initiated.

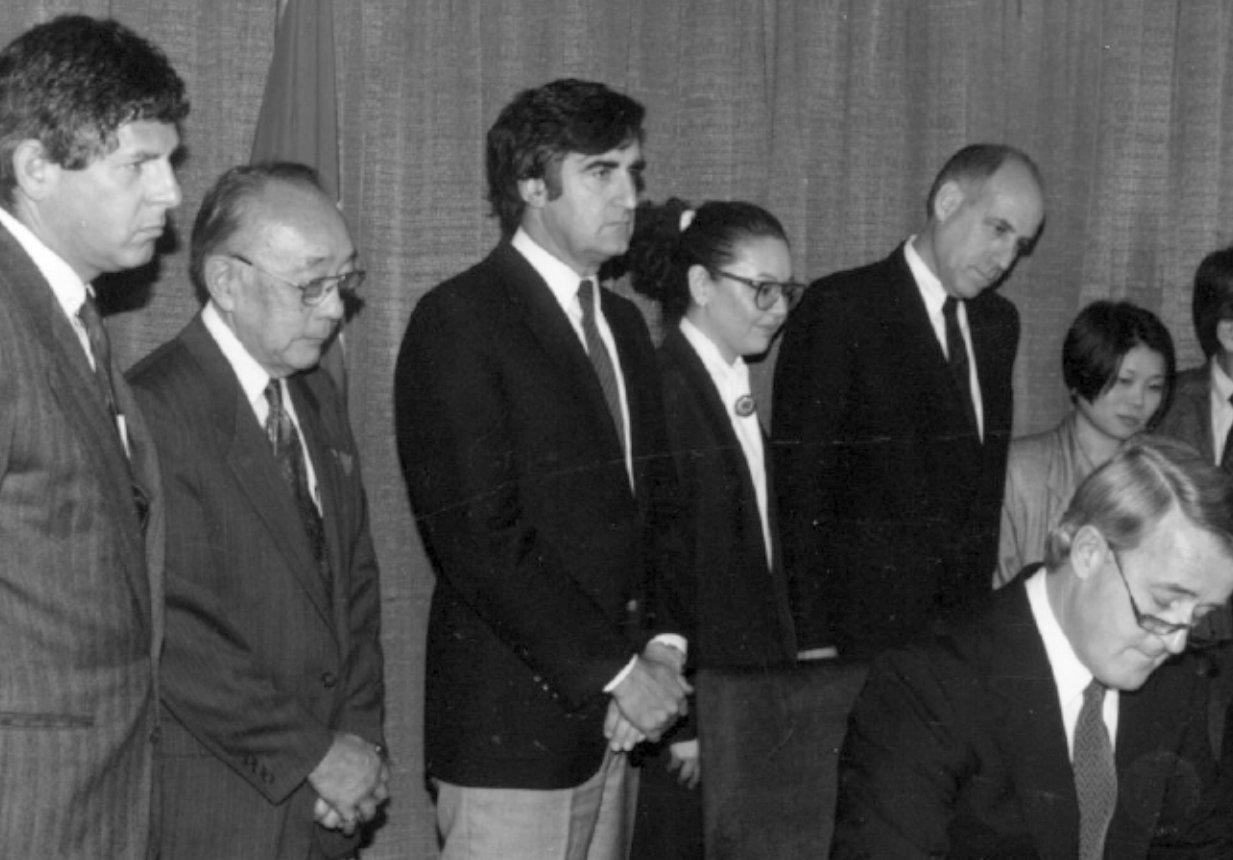

Brian Mulroney signing Redress Agreement. Left to right looking on are Don Rosenbloom, Roger Obata, Lucien Bouchard, Audrey Kobayashi, Gerry Weiner and Maryka Omatsu. (Photo: John Flanders)

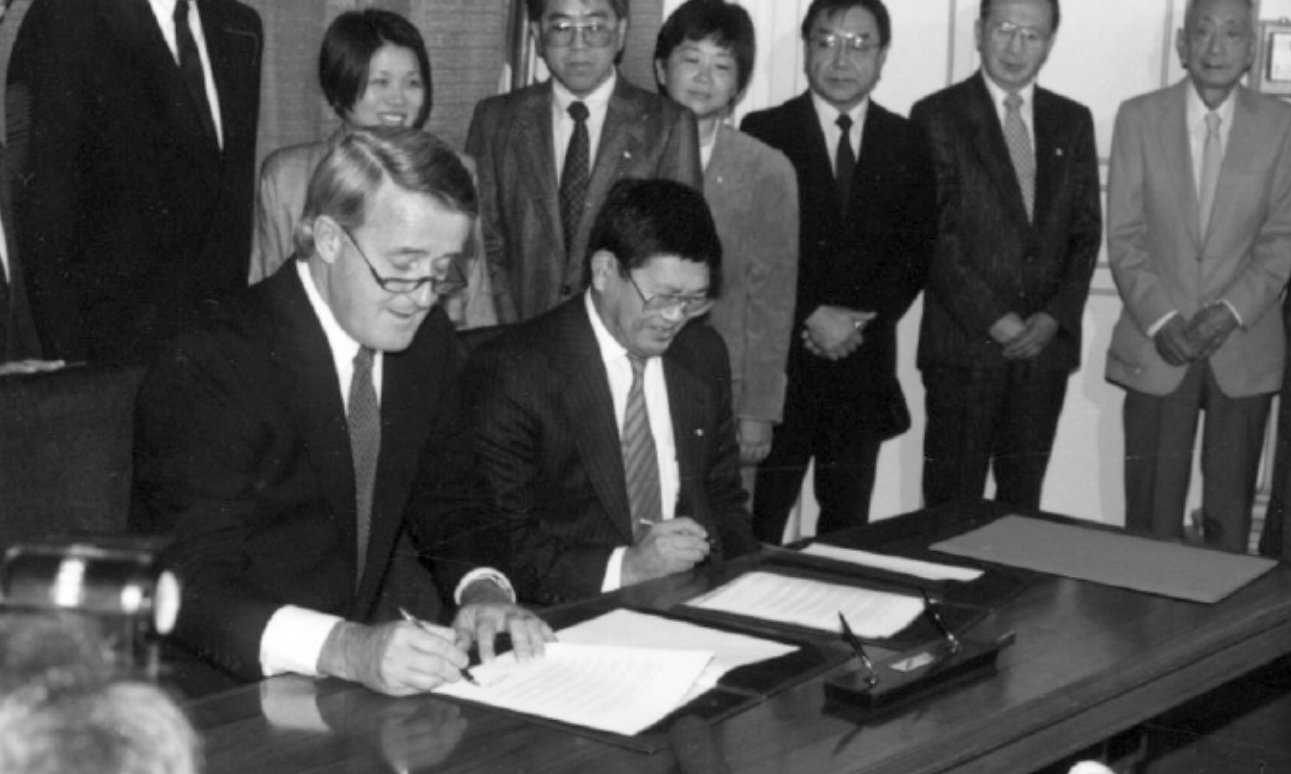

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and NAJC President Art Miki signing historic Japanese Canadian Redress Agreement, September 22, 1988. (Photo: John Flanders)

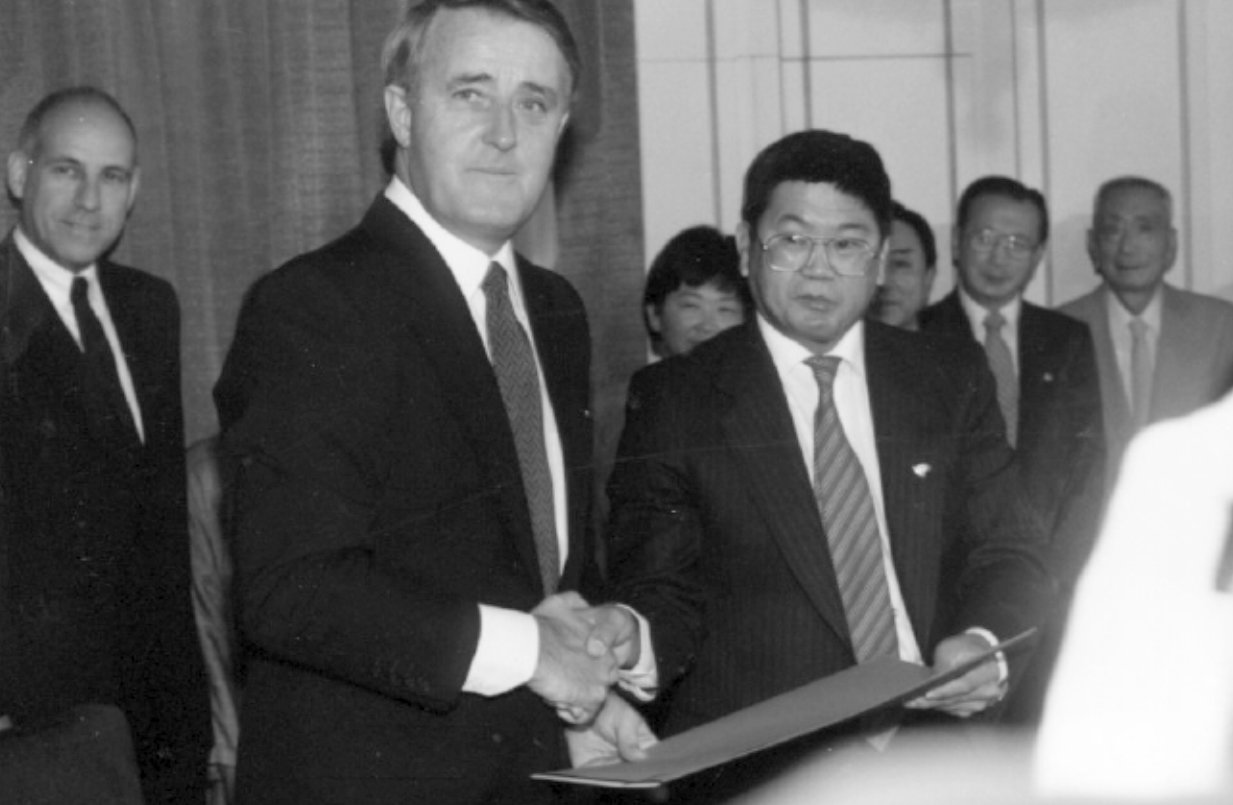

Brian Mulroney and Art Miki shaking hands after official signing of Redress Agreement on September 22, 1988. The Agreement was reached in August, but remained confidential until the official announcement in the House of Commons. (Photo: John Flanders)

Lucien Bouchard shaking hands with Art Miki as Audrey Kobayashi looks on. (Photo: John Flanders)

Roger Obata shaking hands with the Prime Minister. To the left in the foreground is Don Rosenbloom, the NAJC legal advisor. In the background left to right: Audrey Kobayashi, Maryka Omatsu, Roy Miki, Cassandra Kobayashi. (Photo: John Flanders)

NAJC Toronto Chapter President Bill Kobayashi shaking hands with Brian Mulroney after signing of Agreement. (Photo: John Flanders)

Strategy Committee of NAJC with Gerry Weiner and Anne Scotton, who became the executive director of the Japanese Canadian Redress Secretariat. Front Row (L to R): Roger Obata, Art Miki, Gerry Weiner, Anne Scotton. Back Row: Bryce Kambara, Cassandra Kobayashi, Roy Miki, Maryka Omatsu, Audrey Kobayashi, Roy Inouye. (Photo: Jennifer Hashimoto)

Photo of live Redress Settlement broadcast taken from TV screen by Ken Kitamura in Tokyo, Japan. The photo is unique because no still cameras were allowed in the House of Commons. Left to right, watching from the public gallery are Mas Takahashi, Roger Obata, Bill Kobayashi and Harold Hirose.

Multiculturalism and Citizenship Minister Gerry Weiner after his announcement of Redress Settlement at Toronto’s Sutton Place Hotel, September 22, 1988. Joining him at the reception are Polly and Matthew Okuno. (Photo courtesy Blanche Hyodo)

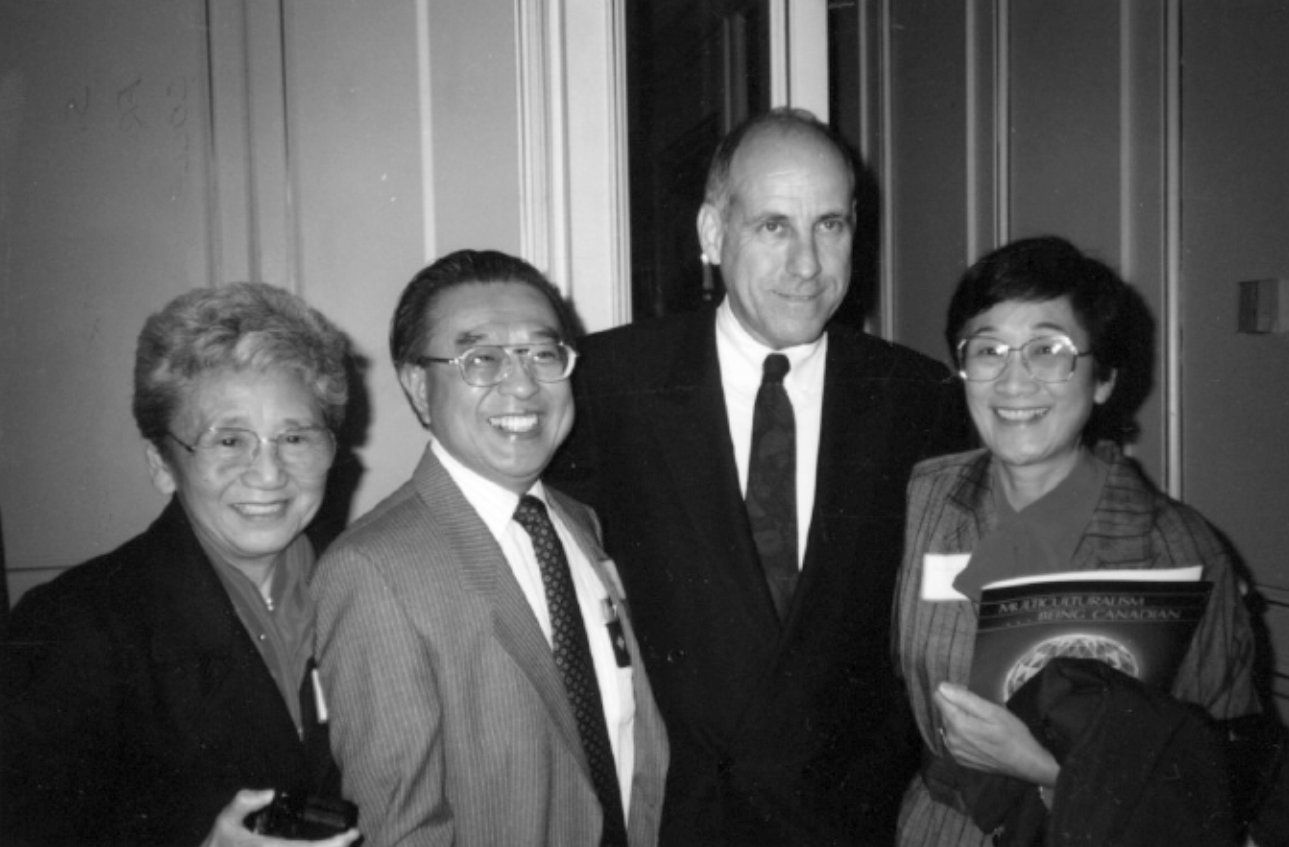

Left to right: Dr. Yachio Yoneyama, Stan Hiraki, Gerry Weiner and Marjorie Hiraki after Weiner’s announcement of Redress Settlement at Sutton Place Hotel reception. (Photo courtesy Blanche Hyodo)

Notes

1 Weiner, Gerry. [untitled speech]. 22 September 1988. Delivered at the Japanese Canadian Redress Agreement Press Conference at the Sutton Place Hotel, Toronto.