Curiosity: First Nations Fiction & Japanese Canadians

by David Fujino.

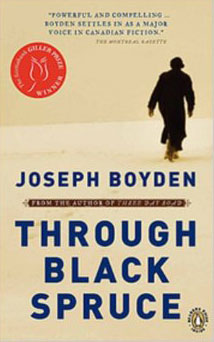

You know when you pick up a novel and read the first few lines, and you know you’ll definitely read it, sooner or later? Well, in the case of Through Black Spruce, it took me over three years before I finally borrowed a copy from the Metro Reference Library at Yonge & Bloor. (Talk about ‘later’.)

You know when you pick up a novel and read the first few lines, and you know you’ll definitely read it, sooner or later? Well, in the case of Through Black Spruce, it took me over three years before I finally borrowed a copy from the Metro Reference Library at Yonge & Bloor. (Talk about ‘later’.)

When I brought the book home, I happily devoured two or three chapters a day, until I was finished. My curiosity was amply rewarded, and what’s more, I caught a glimpse of how Joseph Boyden’s fictional characters saw their world. It was like a direct line into someone’s consciousness.

The characters are Cree. Will Bird is a legendary bush pilot, lying in a coma in a hospital in his home town of Moosonee, Ontario, and his niece, the beautiful and self-reliant Annie, has returned from the seductive worlds of the south — Montreal and New York — to come and sit at his bedside in silent kinship. She has come home.

As their separate stories unfold, shared tales of enduring friendship and fierce love, plane crashes, heartbreak, ancient blood feuds, and murder, eventually unite — in the form of a blessing — for such stories are the intimate ties that bind a family and a people, together.

Now, I’m writing about this novel all because of a comment made by a gentleman who lives in my downtown Toronto neighbourhood. I was telling Jim [not his real name] that I had just read Through Black Spruce, and Jim promptly said he didn’t like literature that tells you what to think and how to think — he doesn’t think that way and he can’t. I could only reply that Through Black Spruce wasn’t like that. Later on at home, I thought about Jim’s comment. Jim hadn’t mentioned any specific book title. He assumed, I guess, that this book belonged to his personal category of First Nations literature — a literature that has, for him, an axe to grind.

However, Through Black Spruce is, rather, a work of fiction and accomplished storytelling, and the sheer pleasure taken in the poetic title, as well as Boyden’s language and his all-too-human characters, count for the many reasons why I, and others, still read and savour fiction.

Consider this: fiction has the distinction of delivering to readers newly created worlds and people we might not otherwise get to meet, particularly people who are different ethnically and spiritually from our selves.

Against the alleged axe-grinding and blaming element in so-called multicultural writing, I wish to offer instead a striking parallel to the Japanese Canadian (internment camp) experience that appears in the pages of Through Black Spruce.

One day, while Will Bird is setting up camp in the bush, he decides to visit the “old settlement”, the grown-over, abandoned Hudson’s Bay Settlement, a place of half-buried memories for Will and his people.

No trees had grown back in around the settlement. Maybe a half-acre of open ground … Long grasses, though, scattered around the fallen husks of old wood buildings. The first was nothing more than ground the building once stood on … I could see what must have been the outline, the biggest here. Company store, I guessed. Maybe the church. One or the other. Always the two, hand in hand. One claiming to take what the Cree didn’t need or want, the other claiming to give us what we were missing. Never clear for me which was which. (p: 263, Through Black Spruce)

Will Bird appears in this scene as an unassuming (not necessarily simple) man, moving about easily in his own element. He revisits the bare physical remains of Hudson’s Bay buildings that once dominated and controlled the lives of his people who are hunters and trappers, and deep memories are triggered — that simple.

It’s always important to remember that novels like Through Black Spruce Spruce aren’t written as journalism or lectures. They’re written because the writer has a story to tell and a desire to tell the story through their own chosen words (language), for language is part of a novelist’s gift and craft. As for the stories s/he writes, the novelist has as much choice in the matter as a leopard chooses to have spots.

Of course, not all novelists — or prose writers — are the same. Some write in what Dylan termed, “finger-pointing” prose; others might write in oblique and poetic ways, but one thing you can say, with certainty, is that not all prose writers are the same.

And the day that we say (as it surely applies in the case of Joseph Boyden and his Giller prize-winning novel, Through Black Spruce) that a writer is a writer, or simply a Canadian writer, we’ll have reached a truly mature and free-thinking mental state.

Many writers — and readers — live for that day.

October 21, 2014

October 21, 2014